Venezuela’s most-wanted rebel shared his story, just before being gunned down

Oscar Perez, the police pilot who commandeered a helicopter and called on Venezuelans to rise up, spoke with journalists in the days and hours before he was killed by government forces

The end had come for Oscar Perez. Blood streamed down the rebel’s face. His men were fighting behind cabinets and ovens as the Venezuelan government closed in on their hideout. Hours later, he and a half-dozen others lay dead on the floor.

Perez, killed on 15 January by government forces, had spent his final years starring in spectacular narratives – sometimes as a hero on the movie screen, other times as a real-life rebel.

He had been the leading man in an action film, a pilot who fought crime from parachutes with a dog strapped to his back. Then in June, he commandeered a helicopter during protests in Venezuela, fired on the Supreme Court and unfurled a banner urging the country to rebel.

While his actions captivated many Venezuelans – and enraged the government – his audience was much diminished in his last days.

But Perez spent many afternoons and evenings in the month before his death crouched over a phone screen, sending encrypted messages to The New York Times. Each side sought to verify the identity of the other by sending short video messages during the exchanges.

The text messages sent in December and January, along with recordings and interviews done over the same period, are some of the last words of Venezuela’s most-wanted man, a rogue police officer who had captured the imagination of a nation, a fugitive fighter who seemed at times to understand his days might be numbered.

“I fight for the freedom of the country, for a better tomorrow,” he began one afternoon in early January, speaking over a messaging application. “The fear of dying is what I have least now. It’s not the fear of death, but the fear of failure, of failing the people.”

Perez’s body sat in a freezer at the Caracas morgue, with two bullet wounds and a cracked mandible, under armed guard. On 21 January, the government released the corpse, which was buried naked, except for a white sheet wrapped around it. Near the funeral, a man flew a kite that said “Liberty.”

Perez was an actor, a detective and an insurgent. To the government he was a terrorist. To his followers he was a freedom fighter, a modern folk hero in the ilk of Robin Hood or Che Guevara. Some sceptics said his story was too improbable to be true – they mused that he must have been a double agent of some sort, meant to cast the opposition in a bad light.

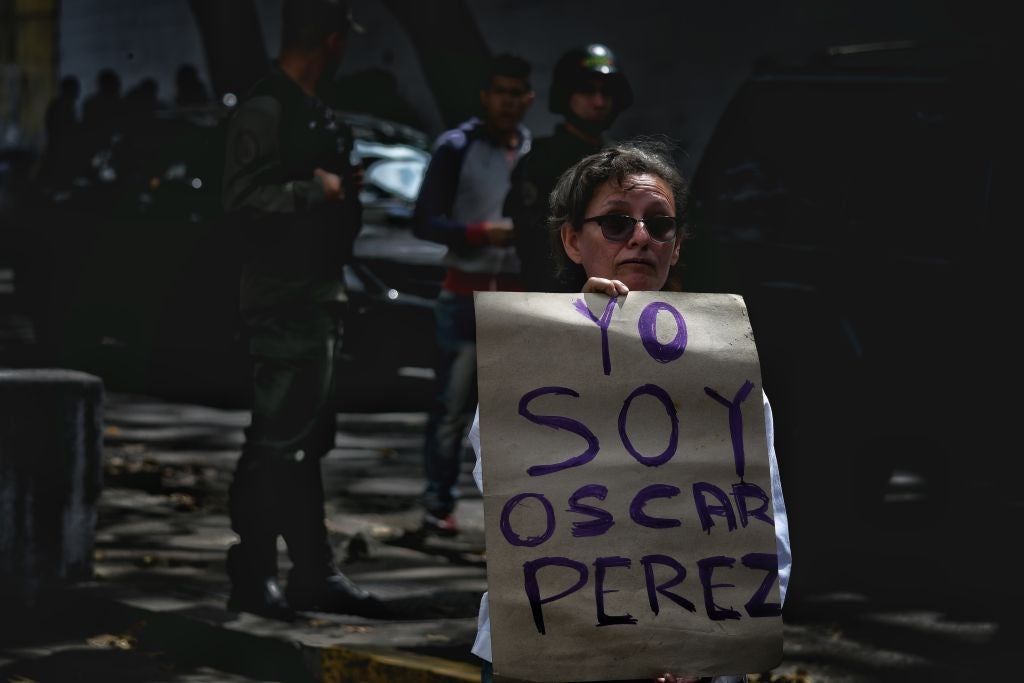

However people viewed him, his actions resonated across the whole country.

Venezuela has suffered from an economic crisis that has left hospitals without medicine and babies dying of malnutrition. An unpopular president has put down protests with an iron fist, leaving more than 100 dead on the streets of Caracas last year among police and protesters. Few seem to hold out hope for democracy in Venezuela.

After his helicopter flight above Caracas in June, Perez became an avatar of the nation’s mounting grievances: he was the daring cop who had defected and asked others to do the same.

But if there is one thing that would haunt him to the grave, it was that the rebellion never came.

“We wanted there to be a call to the streets that day, there to be big displays, that the people realised there a movement had started,” he said in one of his messages. “But unfortunately, there wasn’t one.”

Perez, who joined the investigative unit of the Venezuelan police 15 years ago, might have been just another detective if it hadn’t been for his acting. The film he starred in, Suspended Death, or Muerte Suspendida in Spanish, was released in 2015. He plays an inspector named Efrain Robles who rescues a Venezuelan businessman from kidnappers.

He said the idea to act in the film had come to him after a police operation in a poor neighbourhood in Caracas, where he met a young man on the verge of joining a gang. Perez saw no way of talking him out of crime, but noticed how influenced the young man was by what he saw on television.

“He literally forgot his hunger watching TV,” he said. “It was there you see the great power of audiovisual mediums, of movies.”

The film foreshadows the theatrics Perez would become known for in real life. His character – also a pilot – chases criminals through the streets of the capital from the air, and in the finale, he scuba dives with a rifle to the yacht of the villain.

Perez said the movie also showed the kind of police force that he wished had existed in Venezuela: mug shots displayed on high-tech screens; crime scenes carefully dusted by forensics experts; men in lab coats analysing the results.

But the reality he lived as the country’s economy collapsed was much different, Perez said. “There were no resources left,” he said. “The technicians operating the equipment had to buy their own supplies just to work.”

Other developments began to unnerve him.

Pro-government armed groups, known as colectivos, began to work openly with corrupt police officers to extort and steal. Investigations were blocked, including into shipments of cocaine that Perez says he repeatedly uncovered. He was told to turn the other way, he said. His account of corruption within the police force could not be independently verified.

“They were the ones trafficking the drugs,” Perez said of government officials.

Among them, he said, was Néstor Reverol, now the country’s interior and justice minister. (Reverol faces indictment in the United States for allegedly calling off investigations into drug traffickers while he led the National Guard.)

Perez said he had long thought of using a helicopter to make his dissent known. But last year, his anger joined with that of thousands of other Venezuelans who took to the streets during four months of bloody protests against President Nicolás Maduro. Perez said he blamed Maduro and his administration for what had befallen Venezuela: the shortages, the corruption and the country’s rising crime.

The week before he commandeered the helicopter, Perez’s brother was killed by gangsters in a cellphone robbery, he said. They stabbed him to death two blocks from home.

“I had to identify my brother laid out in the morgue on a steel tray completely frozen,” he said. “You’re a policeman and you see someone so close to you die in this crime scourge caused by this bad government.”

On 27 June, Perez took off in the helicopter, saying it was time to set a public example for Venezuelans.

There were clear skies above Caracas when the explosions sounded: they were from stun grenades thrown out of the helicopter, and they were meant to generate attention without causing harm, Perez said. Then he piloted the helicopter to the Interior Ministry building, where he fired blanks.

As a crowd looked up at the spectacle unfolding in the sky, Perez unfurled a banner calling on those below to rebel.

“It was meant as a wake-up call that they shouldn’t lose hope,” he said. “And not just to the people but also to the public workers that they wake up as well.”

The events stunned the nation. For a time, many wondered whether a coup was underway. But Perez was acting only with a small band, and opposition parties did not take up his call.

When the helicopter suffered a hydraulic failure, he said, he was forced to make an emergency landing in a field. Residents called the authorities, but he got away before they arrived.

He was now a fugitive – but he had the country’s full attention.

On Instagram, he posted photos of himself and other men armed with stolen rifles, usually in groups of four to 10. Three weeks after the attack he made a brazen public appearance, speaking at an anti-government rally, repeating a message which became increasingly admonishing in tone.

“We must recover the values and ethics and the customs of this country,” he shouted that day to television cameras. “It’s our conviction, our legacy. If you are ready, then we will be ready as well – to defend this country!”

But his calls for the people to rise up seemed to be falling on deaf ears. On 30 July, Maduro further consolidated his power, creating a body of loyalists to dismiss the country’s legislature, the only branch of government his party did not control.

The streets were militarised and public dissent was banned by presidential orders. The protests evaporated almost entirely.

Perez’s path would be more isolated from then on. He described a band of around 50 men who followed him, often dispersed into smaller groups and training in safe houses. The number of followers Perez said he had could not be independently verified.

With Perez out of the public eye, the government painted a picture of a dangerous rebel band that it said tried to kill people that day at the Supreme Court. Maduro would frequently say that they and the opposition were plotting terrorist acts to bring the country to civil war.

The accusations irked Perez to the end. “If we had wanted to kill someone that day, we would have already done it,” he said.

Even as the authorities closed in on Perez this month, he was confident he would continue to outsmart them. “We’re always one step ahead of them, thanks to the people who are helping us, my intelligence team that’s inside the institutions,” he said.

Before going to bed the night of his death, Perez messaged The New York Times again.

“Lovely, I’ll let you know,” he said, referring to setting a time for the next interview. It was 12.45am.

In the early hours of Monday morning, Perez posted a video to his Instagram account. Government troops had found him.

At first no shots are heard on the video. Perez calls out to a military major who stands outside, telling the rebel to give up, saying that the state has won. Perez says he will not surrender because he fears they will kill civilians in the building.

Everyone seems calm. But the videos soon show a scene of chaos.

Perez looks into his phone, blood streaming into his right eye. He urges Venezuelans to take to the streets immediately. Bullet holes mark the wall and gunshots are heard in the background. He says that he is offering to surrender but that the government is launching grenades.

In one video, Perez concedes that his time is up.

“May God be with us and may Jesus Christ accompany me,” he says. “Derek, Santiago, Sebastian, I love you with all my heart, sons. I hope to see you soon again.”

Later that morning, Venezuela’s government said the group had been “dismantled”. Perez and six others there were dead. Two police officers were killed, officials said.

Perez’s death, shown on Instagram, transfixed Venezuela, making his last moments his final public spectacle. And almost like in a film, the threads of the life that had led him to rebellion seemed to come together one last time.

Réverol, the official who Perez had said once blocked him from stopping drug traffickers, was among the first to declare victory. He called Perez’s group “a dangerous gang that in recent months launched terrorist attacks”.

Perez’s body, bloodied and still wearing a vest, was hauled to the morgue. There it sat, not far from the place where he had identified the corpse of his brother the year before – and made up his mind that it was at last time to act.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks