‘Regulations kill’ the vibe for Hong Kong’s indie music scene

It’s a buzzing tourist destination vibrant with life and yet, when it comes to music, Hong Kong seems to have lost the beat. Musicians and venue owners tell Mike Ives how restrictive rules are impeding artistic expression and cultural development

Just after the rock band finished its set, a squad of police officers in riot gear swept into the industrial building, past the freight-elevator lobby, and through the doors of Hidden Agenda, a ground-floor music club in Hong Kong.

Shouting ensued, police dogs barked, and four musicians from Britain and the United States dialled lawyers from behind a black curtain that separated them from a bewildered audience, according to people who witnessed the episode on a recent spring evening.

“I am not a criminal,” the club’s owner, Hui Chung-wo, said he told the officers. They arrested him anyway, on suspicion of allowing foreign citizens to perform without work visas. He was detained for 22 hours, he said, and is expected in court this month.

Few indie musicians in Hong Kong were surprised by the raid. Hidden Agenda, for example, has shuttered three previous locations because of regulatory problems since 2009.

“Live houses are always closing down from lack of funds or building regulations,” said Jerry Tse, the bass player in the rap-metal band Sexy Hammer.

Policy experts say Hui’s troubles at Hidden Agenda, the beating heart of Hong Kong’s “live house” indie music scene, illustrate how zoning and performance rules in this city of 7.4 million are so restrictive that they impede artistic expression and cultural development.

Local manufacturers mostly relocated to the nearby Chinese mainland a generation ago, turning acres of vacant factories into ideal spaces for up-and-coming bands to kick out the jams. A handful of entrepreneurs opened clubs that were lean on furnishings but full of cheap beer and youthful energy.

But many of the clubs have folded, often after violating regulations that critics say effectively criminalise most nonindustrial activities. The result is that Hong Kong’s indie bands are forever searching for places to perform – a further indignity for working-class musicians and fans in a financial hub where the night life caters largely to people on corporate salaries.

“We are not just talking about upper-class, high-class art,” Tanya Chan, a legislator from Hong Kong’s pro-democracy Civic Party, said of the music at Hidden Agenda and other quasi-underground venues in the city’s industrial neighbourhoods.

“I don’t see why ordinary citizens or music lovers can’t have their own place to play music,” she added. “If no such choices exist in our city, that’s a pity.”

Hong Kong has fewer than 13 small-scale live houses, mainly in industrial buildings, and seven others, including Hidden Agenda, that would be considered midsize or large, said Adrian Chow, a composer and producer who supervises the music group at the Hong Kong Arts Development Council, a government-funded advisory body.

Many of those venues would struggle to survive even without onerous regulations because the property market is among the world’s most expensive. What’s more, a recent industrial “revitalisation” program gave landlords financial incentives to convert industrial buildings into offices, but it also drove up the value of such space in districts like East Kowloon, a popular area for live houses.

Industrial rents in East Kowloon climbed to $1.77 a square foot in 2015, from $1.05 a square foot five years earlier, a 68 percent increase, according to data provided by Savills, a property consulting firm. The rents there – Hui said he pays about $7,700 (£5,966) a month for his venue in East Kowloon – are still a small fraction of what club owners would pay in commercial districts. But that does not make them more affordable.

“There have to be subsidies by the nonprofit-making community or the government” to enable live houses to survive, said James Siu, head of Kowloon for Savills. Almost no such subsidies exist.

But musicians and policy experts say the regulations on zoning, hygiene and fire safety are at least as big of a headache for live houses, and perhaps even more of a long-term threat to the indie music scene.

A key problem, they say, is that venues in industrial buildings cannot apply for a public entertainment licence unless they buy a prohibitively expensive waiver.

Jeremy Tam, a Civic Party legislator from East Kowloon, said such a waiver would most likely cost a live house like Hidden Agenda $128,000 (£99,187) to $192,000 (£148,780) a year. Failing to obtain one would technically make any concert in an industrial building illegal.

The Lands Department, which partly oversees entertainment licences, said in an emailed statement that a primary aim of its policies was to discourage public foot traffic in industrial buildings, which it said generally faced greater fire risks than other types of buildings.

But Tam said it was clearly possible to alter outdated zoning and performance rules without threatening public safety.

After studying industrial zoning rules in Seoul and London, he said, he plans to introduce legislation that would allow live houses like Hidden Agenda to operate legally on the first three levels of industrial buildings if they met reasonable safety standards.

“It’s the best way to optimise the limited space in Hong Kong,” he said. “That’s how you build a nighttime culture.”

Musicians said in interviews that they were not holding their breath.

Jan Curious, the stage name for the singer in the band Chochukmo, called it ironic that restrictions on live music in this semiautonomous Chinese city were harsher than those on the mainland, where political speech is far more restricted.

The authorities there do not care about policing concerts, he said. “Maybe they’ll come and ask you for money. But they won’t tell you to stop.”

Hanes Cheung, the guitarist for the band Twisterella, said the average live house tended to fold after about two years and the shortage of proper music venues often forced bands to perform in restaurants against their will.

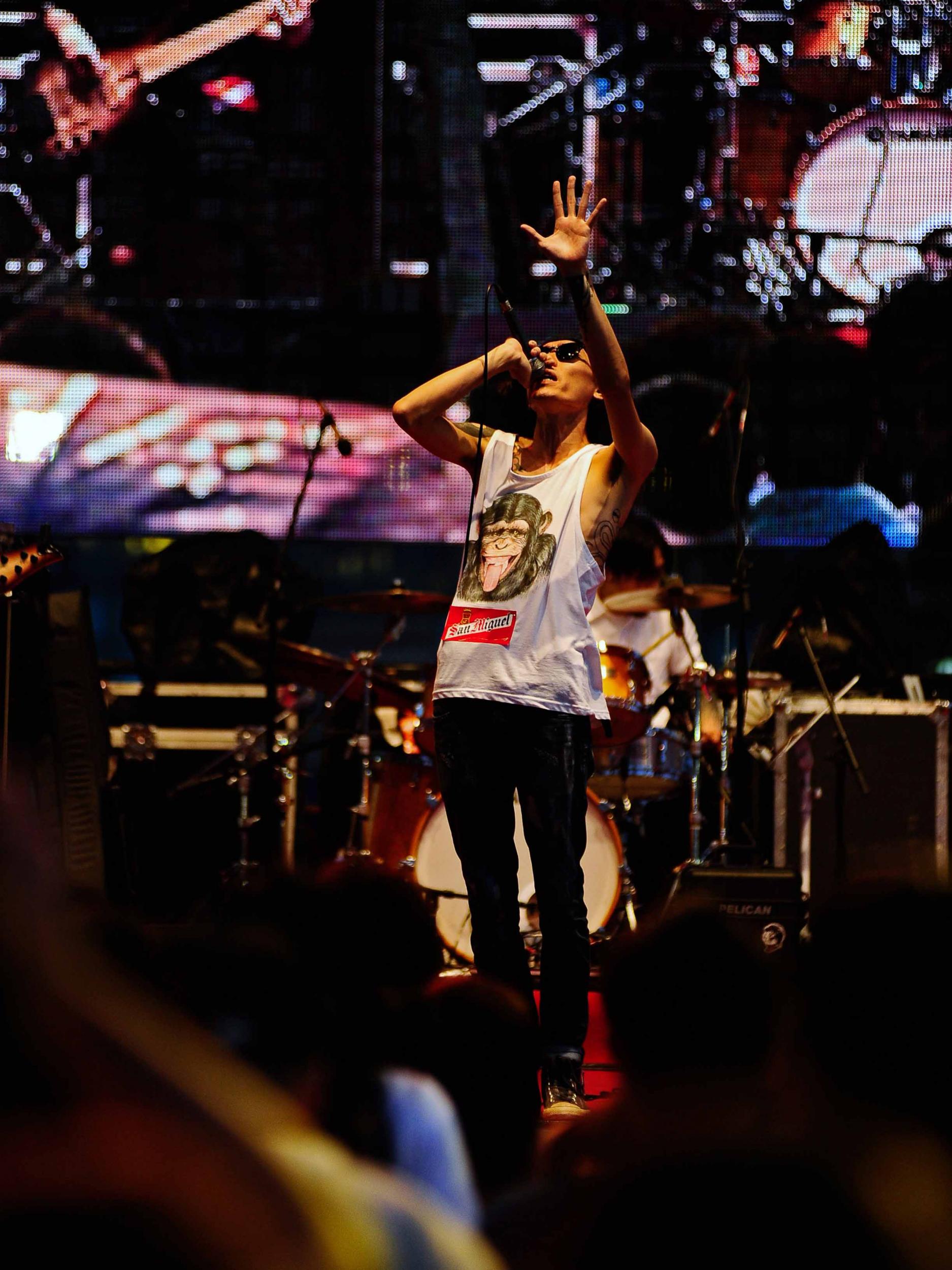

“Regulations kill the whole scene,” he said on a recent Sunday after playing a raucous set at Hidden Agenda as part of an all-day music event.

Hui, the club owner, spent much of the afternoon filtering through a mellow crowd of perhaps 100 people, and occasionally pausing to dance amid artificial fog and pulsing stage lights. He said that the event might be Hidden Agenda’s last, at least until his legal issues were resolved, and that he had lost about $14,000 (£10,848) in June after cancelling five performances that had been booked before his arrest in early May.

Hui, 30, said he did not expect the rules governing the music scene to change because any overhaul could upset long-established relationships between city officials and real estate interests.

Officially designating a live house as a venue would affect developers by altering the dynamics of the property market, he said. “The government doesn’t want to have any argument with them, which is why they’re going to push us away.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments