What it's like to be the brother of Bobby Kennedy's killer

For 50 years, Munir Sirhan has waited for his sibling, convicted of killing Robert F Kennedy, to come home

On a serene, leafy street in north Pasadena, California, a 70-year-old man has lived a quiet life in a well-preserved craftsman house his family bought in 1963. He keeps the lawn mowed. Trims his fruit trees. Chats with the neighbours. Sometimes he smokes Parliament cigarettes with his tea on the front porch, gazing at the San Gabriel Mountains that rise to the north into a sky that’s almost always blue.

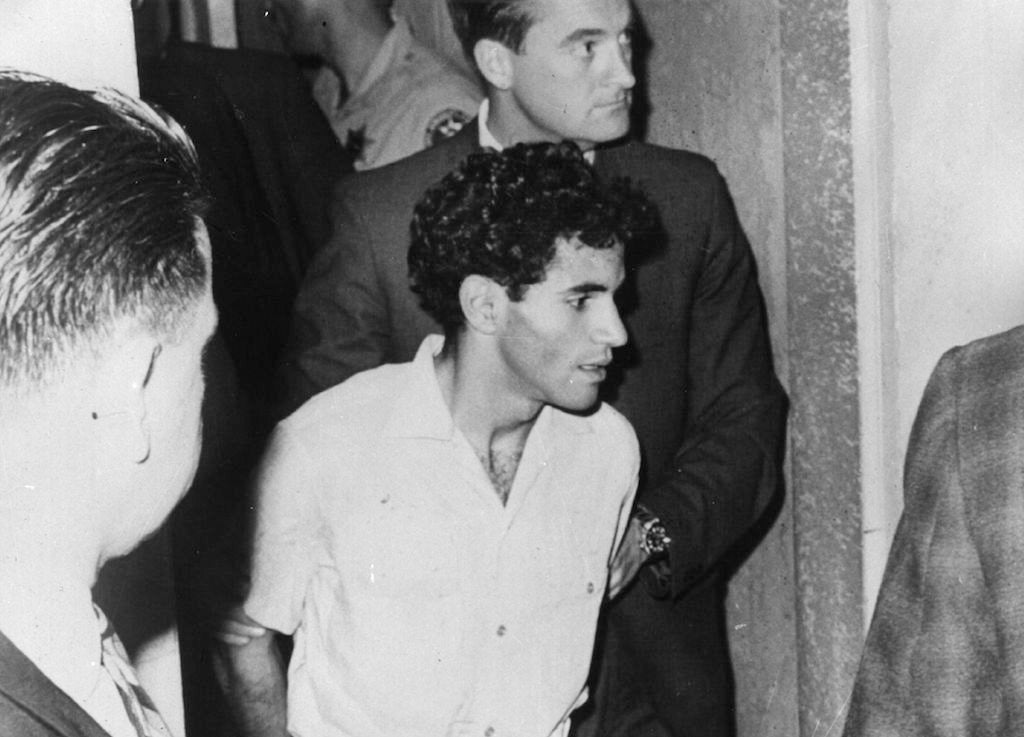

One spring day 50 years ago, one of his older brothers left this house and eventually drove his pink and white 1956 DeSoto to the Ambassador Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles to shoot Senator Robert F Kennedy. At the time, Kennedy was campaigning for the Democratic presidential nomination. To his supporters, he represented a chance to heal the torn and reeling country. On 6 June 1968, he died from a gunshot wound to the head. Sirhan Sirhan was sentenced to the gas chamber for the assassination – a sentence that was commuted to life in prison in 1972.

In the intervening years, Munir Sirhan has cared for another brother, Adel, who lived here before dying of cancer in 2001, and looked after his mother, who died in 2005, blind and deaf after years of illness. His father and three other siblings have died, too. Munir, three years younger than Sirhan, was the baby of the family. Now he and Sirhan are the only ones left.

He keeps the furniture in the house pretty much as it has been since 1968. There’s a grandfather clock that’s stopped at 10:01 in the morning, the moment Adel died. A sign on a shelf says, “The Lord Provides”. Another sign in the kitchen says, “Waiting for the other SHOE to drop!” Small, framed photos of brothers Adel, Saad Allah, Sharif and Sirhan, sister Aida, father Bishara and mother Mary line a high shelf in the dining room, almost too high to see them clearly. The Sirhans were Christians; crosses lean between the pictures.

There are three shelves of books about the Kennedys that Munir bought but has never read. On the floor, vacuum trails are visible in the cream-coloured carpet. When I visit on a Wednesday morning, he looks around the living room, which could not be tidier, and says, “Sorry for the mess.”

The shades are drawn and the lamps are twilight low. Munir is blind in one eye and always wears dark glasses. It’s quiet and still in this place. And then the sound of a robin chirping comes from the kitchen, where there’s a clock with birds on the face instead of numbers. “Every hour is different,” he says. “One hour it’s a mockingbird, and another hour it’s a blue jay and so on. I enjoy it. I live alone. It keeps me company.”

There is no wife, there is no career, never has been. Sirhan’s crime has had a 50-year ripple effect on Munir. He leads a simple existence, keeping mostly to himself while he waits for his brother – who has been denied parole 15 times. “I just want to hear his footsteps on the porch,” Munir says. “I just want to hug him and tell him, ‘Welcome home’.”

***

In 1948, the Sirhans, who were Christian Palestinians, fled their home in the newly divided Jerusalem. The family slipped away during a letup in the fighting of what became known as the Arab-Israeli War of 1948. The Sirhans were granted Jordanian citizenship, but they would come to see America as their future. “There was a program started by Eisenhower and the United Nations to help refugees,” says Munir. In 1956 they left with only what they could pack in suitcases. “Sirhan didn’t want to come,” Munir says. “He ran away. Finally during the morning hours we found him and packed him up real quick.”

A ship crowded with seasick refugees brought the family to New York City. Their sponsor lived in Pasadena, so the Sirhans took the train to this land of sunshine and roses. “It was a new haven, compared to Jordan,” says Munir.

But it wasn’t perfect: “It was difficult fitting in. I think Sirhan must have had this same problem. To this day, people walk up to me and speak Spanish. People think I’m Mexican. Some think I’m black or mulatto... I used to get into fights when I was a child because I would say to an individual, ‘I’m not Mexican,’ and they would think I was putting them down for being Mexican.”

Bishara, the family patriarch, returned to Jordan after about a year, unable to adapt to life in the States. He reportedly beat his sons, though Munir says that was not his experience. Bishara eventually lost touch with his family and stayed in his home village of Taibe until his death in 1987.

Munir’s two eldest brothers adopted the paternal role – not always an easy situation for the younger siblings – but “we were a close family,” he says. “Very tightly knit.” They worked, they pooled their resources, they bought a home. They also bought an Ampex reel-to-reel tape recorder. It hasn’t worked for years but still sits in what was Sirhan’s bedroom, a sunny space at the rear of the house, along with an old cardboard box filled with tapes – recordings of a happy family singing Egyptian folk songs, making music together.

“Adel would play the oud,” a lute-type stringed instrument, “and Mother would take two spoons and hit the bottom of a bottle and approximate a drum sound,” Munir says. “Even if you didn’t know the language or the rhythm of the Middle Eastern music, Adel could make you jump and holler and get off your seat.” Later, the family would use the machine to record the audio from TV news broadcasts about Sirhan. Those tapes are in the box in the bedroom, too, all of them slowly decaying, unplayable.

As an older brother, Sirhan was “very congenial and protective,” Munir recalls. “If anybody was trying to do me any harm, he confronted people.” Sirhan would say: “‘Listen, this is my little brother. I don’t want anybody hurting him.’”

Slowly, the Sirhans became Americanised. They had dogs named Tasha and Blue, a cat named Father John and a hamster named Herbie. They were regulars at Westminster Presbyterian Church, which was in walking distance from their home. Mary worked there in the nursery school. Sirhan went to nearby Eliot Junior High School, and then to John Muir High School – the same school attended by Jackie Robinson, future baseball star – where he joined the Reserve Officers' Training Corp (ROTC) and learned to shoot a .22-calibre rifle.

Munir quit school after sixth grade. “My eyes were weak,” he says. “I couldn’t see the blackboard... I just couldn’t sit through it. So I thought I could learn more outside of the school system than in it.”

The brothers got paper rounds, distributing the Pasadena Star-News. They also worked at a local health food store making deliveries. Sirhan liked to read, holed up for hours in that back bedroom with a window that looked out on a single lemon tree. It’s still there, gnarled and hanging with fruit.

Munir collected records. Had thousands in the garage. He sold them at a yard sale years ago. He says he enjoyed all kinds of music, but who did he really, really like? “I used to love Stan Freberg,” he tells me. In the 1950s and 1960s, Freberg – a Pasadena native – was a popular song parodist, the “Weird Al” Yankovic of his day. “I used to adore that guy. I think that’s what I would have been, some sort of comedy songwriter or something like that.”

But it didn’t turn out that way. He got a job at FC Nash department store in Pasadena as a stock clerk. “The personnel manager, she said, ‘How do you pronounce Munir?’” he recalls. “‘Don’t you have a nickname?’ So I said, ‘Well, yeah, call me Joe.’ I saw it on one of the carpenter’s shirts. She said, ‘Oh well, we’ll have three Joes.’”

This mundane department store position created a connection – with Munir as the unwitting middleman – that would lead to his brother acquiring a gun. The gun. Around January 1968, “Sirhan, because he used to belong to the ROTC, asked me to see if I could get him a gun,” Munir recalls. “And I said, sure, I’ll ask.” A co-worker knew a friend looking to sell a pistol. That co-worker and another individual met the brothers in front of the house one evening and made a deal. “In any event, Sirhan ended up with the gun through me,” says Munir. “Which didn’t make me feel too good as years progressed.”

According to a Los Angeles police interview transcript from 1968, Munir had tried to talk his brother out of buying the weapon. He told the police that he asked his brother to swear on their sister’s memory – she had died in 1964 of leukemia at age 28 – that he would “go to the rifle range just one time and then throw it away.” He did swear – “but,” as Munir told police, “he didn’t carry it through.”

“I’d think: If I hadn’t bought him that gun, or if I hadn’t connected him with” the co-worker, then “things would be different,” Munir says now. “You kind of start looking inward... to see if you were part of the blame for this thing happening.”

***

In the early hours of June 6, Adel Sirhan, who worked nights playing oud at an Arabic nightclub in Hollywood called the Fez, came home and entered Munir’s room. From Munir’s LAPD interview: “I was asleep, and he woke me up and he said that Senator Kennedy had been shot. I woke up. I said, ‘Oh, my God.’ I was hazy and sleepy. I just went back to sleep.”

Later that morning, Munir left the house and took the bus to FC Nash. At about 8:30, he went into the break room. “And the TV was on loud and the room was full,” he tells me. “And usually it’s not that full unless it’s somebody’s birthday, and I’m thinking it’s too early in the morning to celebrate a birthday.” He got some coffee from the vending machine. “So I took a couple of sips of my coffee, and I looked at the screen and the announcer was saying, ‘If anybody knows the identity of this individual, get a hold of the police,’ and it looked like Sirhan. I said, ‘Whoa.’”

“I waited until the picture came on again,” he continues, “and I said, ‘That’s my brother.’... So I took my cup of coffee with me and spilled it all over the place, but ran down to the housewares department and asked my boss if I could use his car to run home. I told him, ‘Listen, I think it’s my brother that shot Kennedy!’”

His boss gave him his car keys. “I came home and told Adel, I said, ‘Hey, they say that Sirhan shot Kennedy.’ I was shaking.” Munir thought police had the wrong person. He had reason to think this was possible: A few years earlier, he had received a citation for hitchhiking. He says he didn’t realise he was supposed to go to court, so the citation turned into a warrant. Later, according to Munir, Sirhan was stopped for driving barefoot. When the officer searched the record of Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, the warrant for Munir Bishara Sirhan came up. The officer arrested Sirhan. “And when this thing happened, I thought: They got the wrong guy. There’s a mistake here, you know, they’ve got him mistaken for another guy, just as they had in the situation with the warrant... That was my solace at the time.”

Munir and Adel went to the Pasadena police station “to notify them, to see what the story was. And the officer, the desk clerk there, didn’t seem too interested with our questioning, so we walked away, and when we walked away Adel happened to gaze at a newsstand, and there it was: Sirhan’s picture on the front page... So he grabbed the paper and went back to the desk sergeant and told him, ‘Listen, this is my brother.’ I remember the guy’s look. He said, ‘Oh.’... And then all hell broke loose.”

***

What Sirhan did that night at the Ambassador Hotel is well documented. The short version is this: A month before the assassination, Sirhan had scrawled repeatedly in a notebook, “R.F.K. must die.” (During his trial, he said he had no memory of writing this.) On June 4, the day of the California primary, he went to the hotel with a .22 Iver Johnson pistol fully loaded with eight bullets. He had four Tom Collins cocktails. A little after midnight in the hotel’s ballroom, Kennedy finished his rousing victory speech. He left the ballroom and made his way through a kitchen pantry accompanied by supporters and unofficial bodyguards, athletes Rafer Johnson and Rosey Grier among them. (Los Angeles police were not on the scene, nor were Secret Service details, which weren’t assigned to candidates in 1968.) Sirhan stepped toward Kennedy and began shooting. Kennedy went down. He was hit twice in the back and once in the head. Sirhan was quickly overpowered and forced onto a steam table, still pulling the trigger. Including Kennedy, he shot six people with eight bullets. Five were wounded.

Sirhan stated then and still maintains that he has no memory of the actual shooting. He recalls looking for coffee, talking with a young woman in a polka-dot dress, then nothing until he found himself being choked on the steam table.

He was 115 pounds and 5-foot-2, and his goal in life up to that point had been to be a jockey; he’d worked as a stable boy at Santa Anita racetrack. So why would he assassinate Robert Kennedy? One theory held that Sirhan hated Kennedy for his support of Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. Munir says Sirhan never verbalised any hatred towards RFK and had no issues with Kennedy’s support for Jews or Israel – though this contradicts comments made by other members of the family, including Sirhan himself, about his feelings towards the Jewish state.

Or perhaps Sirhan – as suggested by psychologist Martin M. Schorr, who interviewed Sirhan in 1969 and was quoted in Bishara Sirhan’s 1987 obituary in the Los Angeles Times – hated his allegedly brutal father and took vengeance on Kennedy, whom he saw as a “symbolic replica” of his father. (“He was a very strict father,” Munir says. “But a lot of people had a tight rein on their kids.”) Or did Sirhan, as has been speculated, feel he was a loser, a failure, and he simply wanted to get famous? Munir’s response: “That’s a bunch of crap. That’s crazy... A lot of people looking into this case, after a while they make up their own conclusions."

Then there’s the second gunman theory. The coroner’s report stated that the shot that killed the senator was fired from no more than three inches from the back of his head, on the right. Witness accounts place Sirhan in front of him and a few feet away at the closest. Moreover, an audiotape recorded in the pantry that surfaced in 2004 reveals, according to experts, up to 13 shots fired – five more than Sirhan’s gun held.

Which leads to the Manchurian angle: Sirhan, according to this theory, was acting under hypnosis, had been brainwashed and was merely a patsy – albeit a potentially deadly one – to draw attention from the actual assassin. “He had played around with the hypnotism. I asked him about it but never got any clear answers,” says Munir. “And he was into the Rosicrucians.” According to the group’s website, “The Rosicrucians are a community of mystics who study and practice the metaphysical laws governing the universe.” Sirhan was a card-carrying member of the Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis; his ID, dated 1966, was found in his wallet when he was arrested. During the trial, Sirhan was hypnotised six times by the defence and the prosecution in attempts to recover his memory of the shooting. To no avail.

At the Sirhan family house, on the living room bookshelf along with Munir’s unread Kennedy collection, is a spine bearing the title “The Laws of Mental Domination.” It’s Sirhan’s book. It’s been there for all these years, along with a few of Sirhan’s other, now musty paperbacks like “Think and Grow Rich,” “How to Win Friends and Influence People” and “Word Power Made Easy.”

Munir has lived for decades with a sense of helpless frustration and confusion about the killing. “I say this for people who loved the senator,” he tells me. “They think that they have a closure, but if they look into this thing, they’ll find out that there’s a lot of unanswered questions.”

After the shooting, Munir says, “all of us, the whole family got lost in this avalanche. I remember Mother saying – God bless her, sweet as she was – that maybe it’s her fault. And then Adel thinking, ‘Well, I work nights so I should have been home.’ That went on for a long time. We couldn’t believe it. It wasn’t in Sirhan to do this. It wasn’t in him at all, far from him. It was far from any of us. None of us were politically inclined. If you would’ve told me any of my brothers did anything like this, especially Sirhan, I’d call you the biggest liar in the world.”

***

After Sirhan’s arrest, communicating with him was not easy for his family. “When things somewhat cooled down, after we spoke with the FBI, after we spoke with the L.A. police and Pasadena police, Mother and I went down to see him,” says Munir of their first face-to-face meeting after the shooting. “Mother asked him what happened. He said, ‘I don’t remember. I don’t know.’”

As people across the country dealt with the shock of the assassination, the residents of Munir’s neighbourhood had their own unique experience. “When it first happened, they had to block off the whole street,” he says. “It was full of people... The police were here for six months, 24 hours a day, guarding us, making sure nobody did us any harm, but I don’t think there was any need for that... Everybody was trying to be as helpful as they could. Our neighbour, Olive, Sirhan used to play Parcheesi with her: she and the rest of the neighbours said, ‘If there’s anything I can do, please let me know.’”

Olive is long gone, but Eileen Sloman, her husband, Peter, and son, Ernie, have lived in Olive’s old house for nearly 30 years. To Eileen, the man next door is just Manny. “I love Manny,” she says. “He’s a great neighbour, and when we’re gone he watches the house. When he’s gone we’ll watch his house... He’s a very soft-spoken person, and he’s a very private person. But at the same time, I know that he would do anything for me and my family, and that’s just the type of person he is.” When she moved in, she adds, “I think he maybe knew some way that I knew who he was. But just over the years, he kind of let me in, and trusts me.”

Sloman has seen the odd tour bus cruise by, and Munir once cautioned her to move her trash cans away from his on pickup day. Sometimes souvenir hunters dig in his garbage.

Munir, according to Sloman, keeps a tidy yard: “He does! And the other day he said, ‘I want your opinion on something.’ So I go out, and he’s redone his garage. He’s going to make it into his man cave.”

Munir lives alone, but his existence isn’t solitary. Sloman says he knows more people in the neighbourhood than she does. He goes to all the block parties. Loves to chat. The man cave is part of all that, a way out of the darkness. “It’s painted circus colours,” she continues. “This bright orange and purple, kind of like a circus tent. He said he just wants to make it into a place where people can come and relax.”

Relaxation has not been an easy thing for Munir. “I don’t understand really what he’s been going through,” says Sloman, “but to know that his last brother has been serving the last 50 years of his life in prison has got to be just horrible. Tearing him apart.”

***

Munir says he’s never had to deal with any serious negative backlash due to his last name. Nothing physical, not even verbal. In the early days, “the whole family protected me,” he says, like “where the baby elephant is between the mass of elephants.”

As he got older, even out there in the working world, it wasn’t an issue. He never had a profession – “I’m not that kind of guy” – but worked as a service station manager on and off. “Oh yeah, I had jobs that my name would be printed on my shirt,” he says. “But no, I’ve never had anybody that held any animosity toward us at all. And in fact, I didn’t like it, but a lot of people would say, ‘You’re famous,’ or they would go out of their way to help because of the notoriety, and then I tell them, ‘Please, you know, I have my own individuality.’”

But his own individuality – his own time – has come down to this: “It’s all dedicated to Sirhan. I wait for him to call when he can. When he can’t, I’m here for the attorneys in case they need anything.” And between those phone calls, between helping the attorneys? Munir shrugs. “Go to the store, go to the laundry, go to the post office. Read and read and do some more reading.” About what? “I do a lot of house repairs. I butcher up the place, so I have a lot of manuals about repairing houses. And I read briefs about Sirhan... There’s about 15 boxes of those. My eyes aren’t that great, and I like to keep them reserved for the important issues regarding Sirhan’s case.”

Since 2013, California state prisoner B21014, Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, has been locked up at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility in San Diego – the fifth institution he’s resided in, also home to the Menendez brothers and former Manson family member Tex Watson. It’s 160 miles and a world away from Pasadena.

Seeing him has been up to the vagaries of the prison system, Munir says. When he and his family visited over the years, “it was hard to have time to discuss much of anything. The time we spent with him was discussing legal matters, and we’d be more concerned about his health and if he’s getting treated right.”

They communicate mainly by phone these days, and even those moments are unpredictable. But when Sirhan and Munir do speak, beneath the legal concerns and the health issues, he is still just talking to his big brother, the guy who looked out for him so long ago. “Stop smoking, it’s bad for you,” he says his brother tells him. “It’s the number one killer in the United States. I need you alive.”

Munir lights another Parliament. “You can’t imagine how many press people the family members have spoken to and nothing has changed,” he says. “We go through this every so often and, believe me, it gets monotonous. Don’t take this personally, but we’re private.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments