A third thumb? Our changing attitudes to human enhancement

What would you do with a third thumb? Ashley Coates looks at the emergence of new prosthetics and considers the growing debate surrounding human augmentation

“Now after wearing it on and off for so long, I do feel like it is an extension of my hand,” says Dani Clode, a Royal College of Art student who created a “third thumb” as part of her MA dissertation project. “This is a similar kind of feeling to driving, or using a sewing machine. You don’t think about putting your foot down after a while, you think about moving forward and your foot just goes down.”

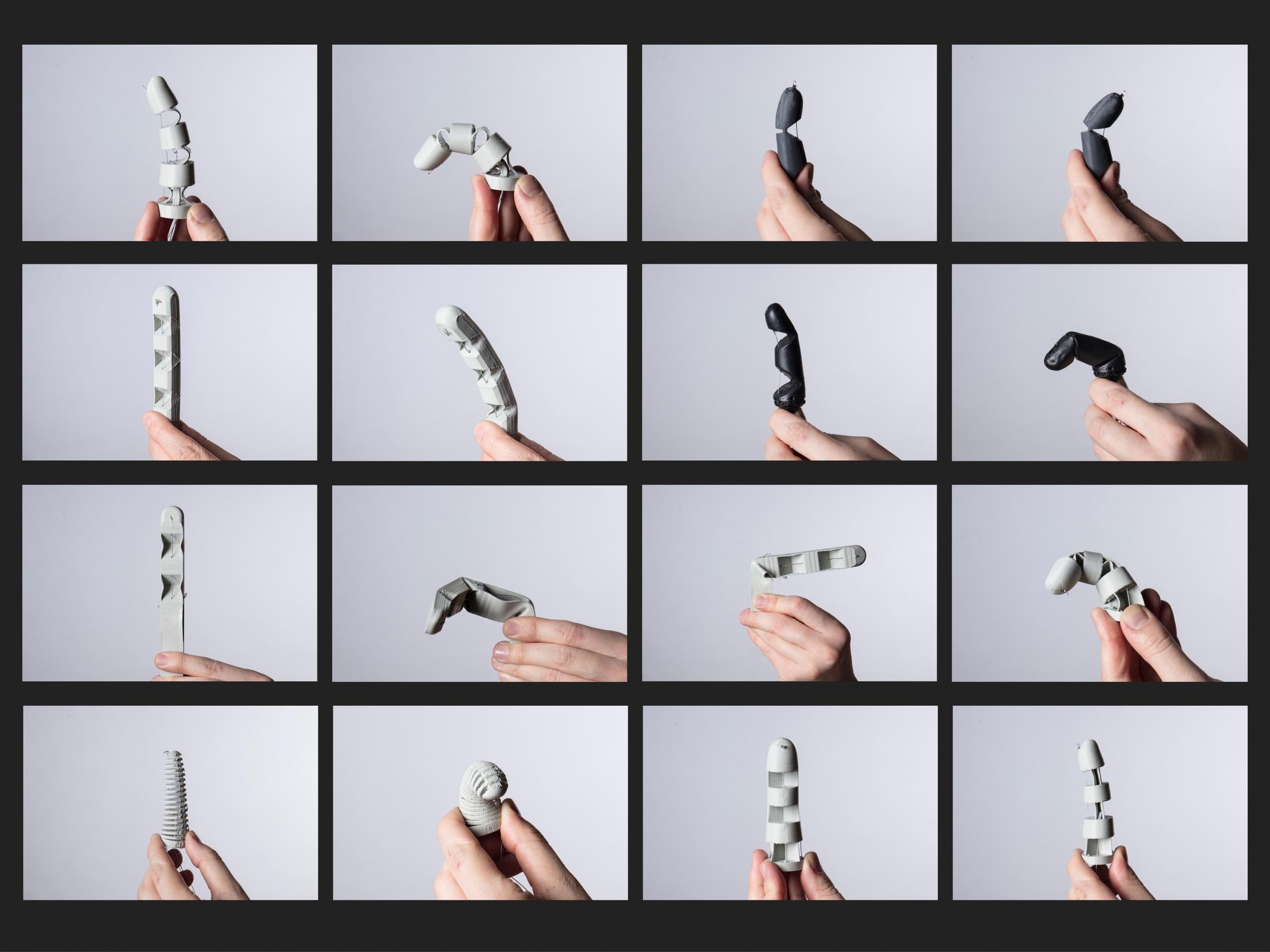

Completed earlier this summer, the Third Thumb Project consists of a 3D-printed prosthetic thumb, which is attached to the user’s hand, while a bracelet receives signals from a bluetooth device that detects movements in the wearer’s foot. To operate the thumb, the wearer just has to press down with one of their feet. Those that have tried it say operating the extra thumb becomes quite natural after a time. For Clode, the Third Thumb Project aims to change the way we view prosthetics, from something that we think of as replacing a function that is lost, to a useful add-on to our day-to-day capabilities.

“It’s one of our favourite projects so far,” Sersah Kombos of B3 Studio told me. Kombos used an advanced form of 3D printing to help make Clode’s vision a reality. “Stereolithography often results in the best surface finish and produces parts that can compete with traditional manufacturing methods in quality and strength.”

For Clode, the Third Thumb Project aims to change the way we view prosthetics, from something that we think of as replacing a function that is lost, to a useful add-on to our day-to-day capabilities.

“I came across the origin of the word prosthesis and found that it meant ‘in addition to’. This inspired me to rethink prosthetics as extensions, rather than anything that ‘fixes’ or ‘replaces’.”

“Prosthetics are such unique products; it’s a product relationship that is unlike any other, and I wanted to really explore the connection that develops between the wearer and the limb, so I wanted the design to be able to be experienced by anyone.”

It’s a nod towards a field known as human augmentation or “Human 2.0”, the idea of adding to our cognitive or physical abilities to make us “better than well”. One interpretation has it that this process has already begun, through cosmetic surgery and reproductive aids on the physical side, and neurostimulation and dietary supplements to enhance brain functions on the cognitive side. Other philosophers see the latest developments in augmentation as the next step in human advancement that started with making primitive tools thousands of years ago and has progressed as far as developing the internet and mobile devices we use today.

In its more advanced form, futurists are predicting that we will all become cyborgs of some kind in the future, making use of a range of biotechnology to improve our vision or athletic performance, add entirely new senses, lengthen our lives, or even avoid death entirely.

Setting aside the medical adoption of devices such as pacemakers and prosthetic limbs, biohacking with a view to making a significant improvement or change to an individual's life has in large-part centred around a DIY biohacking culture. A number of body augmentation enthusiasts have experimented with inserting magnets under their skin, giving them the ability to “sense” electromagnetic fields. As well as being able to pick up metal objects, these experimenters say their sixth sense serves a practical purpose, vibrating when their phone is ringing, or alerting them to the presence of electrical equipment.

One range-finding sensor developed by a company called Grindhouse Wetwares gives the user the ability to sense the rough dimensions of a room by delivering a buzzing sensation to the fingers depending on the proximity of the walls.

Biohacking has a significant following, and is an offshoot of a movement that sprung out of “transhumanist” thinking in the 1980s, where scientists and philosophers speculated on the possibility of a bionic future. On a more scientific level, the British engineer Kevin Warwick says he has been able to benefit from new sensory experiences by installing microchips and electrodes to make himself “the world’s first cyborg”.

Known as “Project Cyberborg”, Warwick’s research began in 1998 with the installation of an RFID transmitter into his arm. Sensors dotted around Coventry University activated lights, opened doors and switched on computers as Warwick passed through them.

He even managed to programme his computer to say “Hello, Professor Warwick” as he entered his office. A controversial figure, Warwick’s work has been both celebrated as forward-thinking, and derided as entertainment and unscientific. Warwick insists his work is about becoming a better human, and seeing how far today’s technology can be used, rather than acting as a human robot.

In another experiment, Warwick “hooked up with” his wife, installing a system that would allow the couple to experience each other’s senses. “It didn’t feel like pain or heat or seeing,” Warwick told Netapp’s Emma Byrne.

“It was like an entirely new sense. And that was part of the experiment: to see if the brain can adapt and take on new types of input and learn to understand. The brain is very clever like that—I just want to see how far we can push it.”

Today, there are a number of institutions working on various forms of human augmentation. At Columbia University, psychologists are finding ways to get around fatigue brought about by less sleep through transcranial magnetic stimulation, bringing about increased brain activity.

Another group at Sarcos Research has developed a set of mechanical legs that can make a heavy weight on your back feel significantly lighter.

Engineers at Boeing’s Phantom Works in Seattle are experimenting with ways to have individual pilots fly whole squadrons of drones through infrared spectroscopy.

The use of human enhancements in warfare has added to the ongoing debate over the ethics of augmentation, particularly the bioengineering aspect. In the not-so-distant future, truly advanced soldiers that have taken on a range of abilities for combat could fall foul of the laws of war.

Much of the emerging technology in this field is coming from military R&D, but while states are busy experimenting with neuroscience, robotics and biology to improve human performance, international law assumes all soldiers are physiologically the same. According to Patrick Lin, associate professor of philosophy at the California Polytechnic State University, our current framework of international laws are not prepared for the advent of enhanced human soldiers on the battlefield. Lin writes:

“Should enhancement technologies – which typically do not directly interact with anyone other than the human subject – be nevertheless subject to a weapons legal-review?”

“That is, is there a sense in which enhancements could be considered as "weapons" and therefore under the authority of certain laws?”

“If we want to say that robots are weapons but humans are not, then we would be challenged to identify the point on that spectrum at which the human becomes a robot or a weapon.”

Away from the military applications of this technology, some futurists fear an “arms race” as individuals with the resources to modify themselves and their children become more able, leaving people from poorer backgrounds unable to compete. This is a particularly worry in the field of mind enhancing drugs, which are already widely available, but could become a more acute problem as availability and acceptability increases..

Other commentators have suggested that significant alterations will have the effect of homogenising identities, as we rush to gain an evolutionary advantage on our peers by adopting similar technologies.

For Gennady Stolyarov, an author who writes on transhumanism, the development of human augmentation is likely to bring about greater diversification of people and interests, much in the same way the widespread adoption of smartphones have allowed people to express themselves and their differences in new ways, rather than forcing greater similarity. This is already the case in the community of biohackers, who are using today’s technologies to make their extra senses part of their identity.

Speaking to the BBC, Stolyarov argued: “Different people would choose to augment themselves in different ways, stretching their abilities in different directions. We will not see a monolithic hierarchy of some augmented humans at the top, while the non-augmented humans get relegated to the bottom.”

Much like our attitudes towards self-driving cars, it is likely that human augmentation, particularly of the sort that involves any kind of technology inserted into the user, or a prosthetic attached to them, could take years to become a widely accepted practice.

Dani Clode doesn’t consider her Third Thumb Project to be biohacking in the strictest sense, but does foresee a change in attitude. “The perception of biohacking is evolving as it becomes more publicised. It’s about blurring the line between our bodies and technology, and that is really interesting. We currently have so many layers between us and technology like our phones for example.”

“By layers I mean, we hold our phones in front of our face, we have to interpret information with our eyes or ears, process that information, and then output it in physical form to our bodies to then react or respond, such as type on a keyboard with fingers on a screen or a physical keyboard.

“We rely on our bodies quite significantly when interacting with technology. I think ‘biohacking’ is about exploring the possibility of reducing those layers.”

It may be many years before we see people adopting the sort of implants used by the world’s biohacking enthusiasts or scientists such as Kevin Warwick, but as we head towards greater human augmentation, the debate around how much we modify our abilities, and the extent to which augmentation can be regulated, could cause a headache for lawmakers and ethics professors alike.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks