Trips and trysts: The Count and the senorita of Bavaria

He was known as the Yankee who could do everything – which he did. She was a ‘Spanish’ flamenco dancer who stole the heart of a king. In this extract from his new book, journalist and author Peter Millar charts the contrasting lives of two unlikely Germans

On Munich’s Maximilianstrasse, which leads up to the Bavarian parliament, there is a classical statue of a bewigged and cloaked 18th-century European gentleman. It is unremarkable except for the bronze lettering on its plinth which reads, in German:

Benjamin Thompson

Count Rumford

Born in Woburn, Massachusetts

Yes – one of the most fascinating figures in Bavarian history was an American. Or rather, I should say, he was born in America. Benjamin Thompson considered himself, as did most of those around him at the time of his birth in New England in 1753, an Englishman, yet he would attain greatness as a Bavarian.

In the course of an extraordinary life, he would make a name for himself as a womaniser, linguist, scientist, landscape gardener, military quartermaster, officer in both the British and Bavarian armies, in the end venerated even by a president of the country he abandoned, the United States.

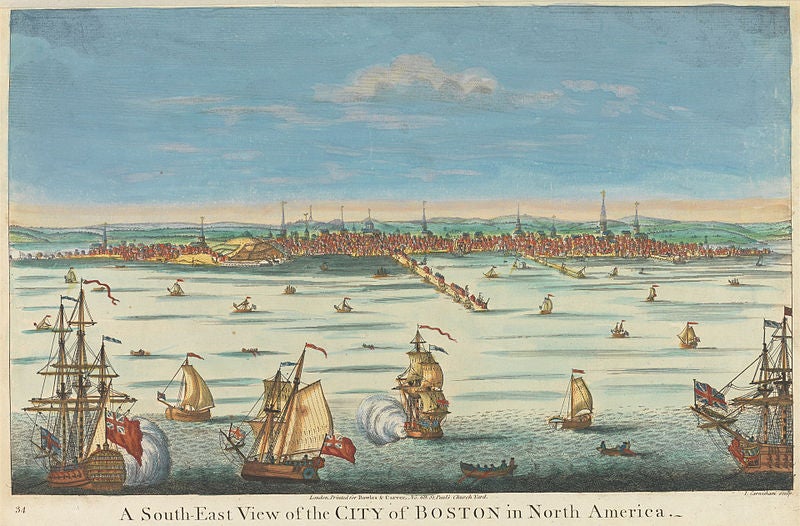

Born to a farmer called Ebenezer in the small town of Woburn, just under 10 miles northwest of Boston, in what is now Massachusetts, Thompson trained at nearby Harvard for a life in business, but ended up as a teacher in a town called Rumford – from which he would later take his title – but is now Concord, New Hampshire. At the age of just 17 he married a well-connected widow 13 years his senior and through her got to know the local colonial governor, who named him a major in the New Hampshire militia at the age of 19.

As local resentment against the British grew, Thompson made clear whose side he was on, which resulted in a local mob attacking his house. He responded by fleeing, abandoning his wife and their two-month-old daughter, to take up a position with the British army in Boston.

On a visit back to Woburn in 1775 the rebellion erupted in earnest with skirmishes even in Rumford; he was put on trial as a suspected British spy, but got off. He immediately cashed in all he had and the following year took a Royal Navy ship to England, found a job in the Colonial Ministry and began conducting scientific experiments with gunpowder, developing an improved method of ship-to-ship communication and better cannons, endeavours which were rewarded in 1779 with membership of The Royal Society.

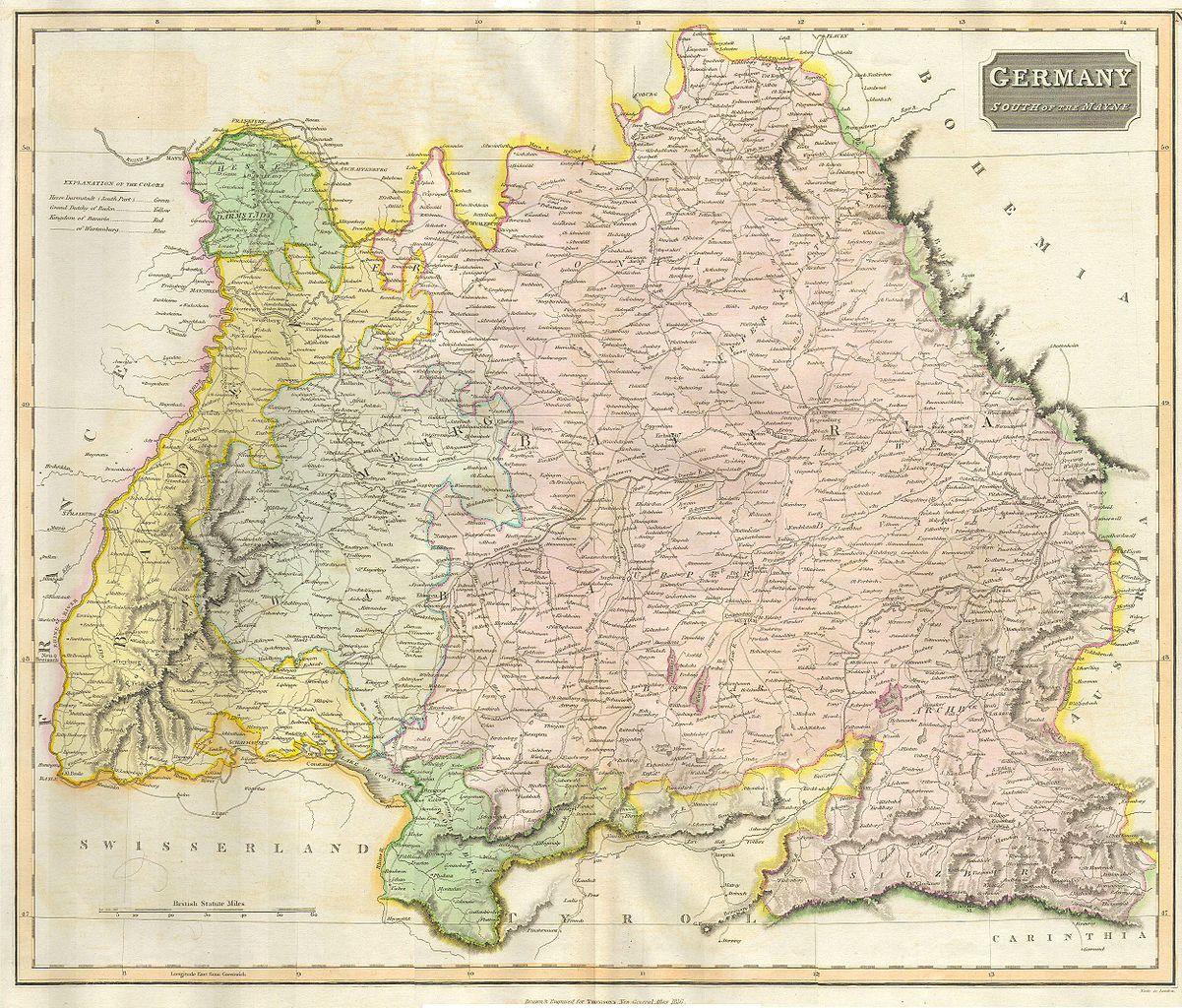

The following year he was given the less-than-promising job of Secretary of State for the American Colonies, by then in full rebellion, and in 1781 crossed the Atlantic again, set up a cavalry regiment called the King’s American Dragoons, and as its commander took charge of Fort Huntingdon on Long Island. But by 1783, with the British on the verge of surrender, he returned again to England, where he was promoted to colonel, but chose instead to travel to the Continent where, in Strasbourg, he bumped into the nephew of the Bavarian-Palatinate elector, who offered him employment.

After a brief return to England to say farewell to George III, who gave him a knighthood as a parting gift, he moved to Munich and began a reorganisation of the Bavarian army. One of his main achievements was the invention of a cheap but hearty soup of potatoes and peas, which solved the problems of undernourishment among the troops, whom he ordered to set up a vegetable garden in every garrison.

At the same time he began planning what remains his most lasting achievement, the layout of a vast tract of land outside Munich’s city walls in the English style – as developed by Capability Brown at Blenheim, north of Oxford – which to this day is called the Englischer Garten.

The park was opened to the public in 1792 and remains a great green lung of 1.6 sq miles. Among the world’s great urban parks, it’s bigger than both Hyde Park and Central Park in New York. The Englischer Garten, despite being bombed by the British in the 1940s, remains one of Munich’s glories, with several chestnut tree-shaded beer gardens, of which perhaps best is the Chinesischer Turm, a mock Chinese pagoda (rebuilt after being burned to the ground by British bombing raids in 1945), the first floor of which on sunny holidays hosts an oompah band.

At the garden’s southern end, where a tributary of the River Isar gushes out from underground, there is a virtually year-round queue of surfers waiting to take their turn on the so-called standing wave. The Isar tributary’s icy grey-green waters provide another daredevil entertainment in summer: jumping into the water from the bank and then fighting the fast-flowing current to get to the edge and climb out. Popular among Munich teenagers to be swept along several hundred metres by the icy flow, from the entrance to the park to the bridge near Tivolistrasse.

It is standard for drinkers coming back into the centre of town from the Chinesischer Turm beer garden on the No 18 tram to find themselves squeezed against a gaggle of teenage girls in bikinis or teenage boys in swim shorts, dripping wet. They are rarely asked for their tickets, not least because in the less conservative 1970s, the girls wore nothing at all. Rumford would almost certainly have approved.

Ever the polymath, at the same time as mastering garden layout, he was also working on scientific investigations into the nature of heat-generation and preservation. Using practical experiments in the cannon-boring process, he discovered one of the basic principles of thermodynamics: that heat was a form of energy and could be produced by movement. He invented several types of devices for heating food (including an early coffee machine) and accidentally discovered the – nowadays extremely trendy – principle of cooking at very low temperatures, by leaving a mutton shoulder overnight in a box designed for drying out potatoes, returning the next morning to find it perfectly cooked through.

His proficiency in almost everything he touched led to promotions through the ranks of the Bavarian army from major general to commander-in-chief and eventually Minister for War and chief of police. He was made a count of the Holy Roman Empire, taking the title Graf von Rumford.

In 1796, with the Bavarian elector on the run after defeat in yet another war with Habsburg Austria, Rumford negotiated a peace treaty which prevented the destruction of Munich, at the same time writing a book On Chimney Fireplaces as a means of improving domestic heating. From 1799 he served effectively as Bavarian ambassador to London. It is a measure of the respect he earned, even from the country he had abandoned, that as early as 1789 he had been elected a member of the Academy of American Arts & Sciences, and received – but rejected – an invitation from US President John Adams to set up an American military academy, the institution that later became West Point.

He visited Paris in 1801 and met the man who would cause more commotion in his adopted homeland of Bavaria – indeed throughout Europe – than he or anyone else could have imagined: Napoleon Bonaparte.

When the French armies that same year forced Bavaria to renounce its Palatinate territory west of the Rhine, Rumford was entrusted with evacuating important cultural treasures back to Munich. He moved to Paris in 1802, was elected to the Institut National des Sciences et des Arts and and settled there, living on his Bavarian state pension, and briefly married to the widow of the guillotined chemist Antoine Lavoisier. He died in 1814, leaving the equivalent of $50,000 to Harvard University, which set up a fellowship in his name.

No sooner had Count “Benny” Rumford departed the European stage, another figure to rival him – at least in eccentricity, aspiration and fame – arrived, also as it happened, on the streets of the Bavarian capital, Munich. To all appearances the exotic figure of Lola Montez was a talented Spanish flamenco dancer from Seville who came to fame among the European nobility when she danced “Los Boleros de Cadiz“ in front of King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia and Tsar Nicholas I of Russia in Berlin and followed up with a tumultuous appearance in Warsaw.

But a succession of torrid affairs saw her rejected by polite society. A run at the Paris Opera increased her fame, as did flirtations with the bestselling novelist Alexandre Dumas and the composer Franz Liszt, but ended in scandal when another lover, the renowned editor Alexandre Dujarrier, was killed in a duel. By the time she arrived in Munich in October 1846, the exuberant 25-year-old was running from a notorious recent past, while still concealing her real origins.

For the woman who gave her full name as Maria de los Dolores Porrys y Montez, was actually Eliza Rosanna Gilbert, daughter of a Scottish father and Irish mother, who had spent her early childhood in Calcutta, mostly grown up in the home of her step-uncle in Scotland and then gone to school in the southern English spa town of Bath, before marrying a British army officer at the age of 16 and going back to India with him.

But Eliza got bored and by 1842, at 21, she was back in England, learning Spanish and reinventing herself as a flamenco dancer, despite having made only one short trip to Spain. Whether or not the chief of the Bavarian court theatre saw through her, he would not allow her on stage until she managed to wangle an audience with King Ludwig. The 60-year-old, the king was so besotted with this exotic young woman that he insisted she be allowed to dance at the court and Bavarian National Theatre, put her up in a hotel and then in a private apartment in the city centre.

The fact that His Majesty’s government thought he was being played for a fool was reflected in the fact that her housemaid was a police spy who would later accuse her of taking students into her rooms for sex at night. Ludwig, who spent most evenings between 5pm and 10pm with her, had her portrait painted for his Schönheitsgallerie – the Gallery of Beauty – in his summer palace; he also gave her a grand house of her own in central Munich.

Given that her only identity papers consisted of a travel document issued by the tiny Thuringian principality of Reuss-Ebersdorf, where she had first found her feet in Central Europe, Ludwig insisted that she be granted Bavarian citizenship. The whole of the king’s cabinet refused and demanded her dismissal; instead they were dismissed. Lola was made not only a citizen, but a countess, a series of events that unleashed popular riots.

She seemed to seek out scandals, although for a young woman still in her 20s who had a kingdom to play with, perhaps nowadays it is not so hard to understand. There are more recent parallels. She would lead her dog, Turk, through the streets of Munich, smoking, and soon assembled a “bodyguard” of young students, nicknamed die Lolamannen (Lola’s lads), drawn from the university’s Alemania fraternity, which thereby incurred the enmity of all the others.

Lola soon became involved in a sexual relationship with their leader. Before long she was sacking professors and lecturers at will, which led to a riot when she was recognised in the street near the university and had to flee for her life. The king ordered the university closed for a term and all students to leave the city within three days.

They responded with a mass protest, backed up by the landlords who rented them their rooms. Crucially, the anger at Lola’s behaviour in the early months of 1848 corresponded with the wave of popular revolution sweeping the rest of Europe’s capitals, including those of the maze of German dukedoms, archbishoprics, principalities and kingdoms. Whether from Ludwig realising his folly or yielding to his ministers, who feared popular revolution and used the “Spanish dancer” as a pretext, a spectacular U-turn took place: the university reopened the following day, and Lola did a moonlight flit to Switzerland.

The crowds on the streets of Munich turned out to cheer. One man, Count Maximilian von Arco-Zinneberg, managed to pick one of her cigar stubs from the gutter, which remains in the Munich City Museum to this day. A month later Ludwig declared she was no longer a Bavarian citizen. A warrant was issued for her arrest. But it was alleged she had secretly returned to the royal boudoir while revolution was stalking the streets, and Ludwig was forced to abdicate in favour of his son, declared Maximilian II.

For the next year Lola lived in Switzerland, writing regularly to the ex-king and receiving regular sums of money in return. In 1849 she moved back to London and married another British officer, only to be charged with bigamy because her first husband, whom she had not bothered to divorce, was still alive. True to form, she fled again.

By now the elderly and still besotted Ludwig wised up and severed all contact. Lola had done well out of it. Shortly after her first performance in Munich he had changed his will to grant her a bequest of 100,000 guilders if she remained single after his death, and an annual stipend of a further 2,400 guilders. By 1850 when the relationship came to an end, she had acquired from the royal purse some 158,000 guilders (equivalent to £1.5m today). Lola made a few brief efforts to revive her Spanish dancing career in France, wrote up her memoirs then moved to the US where she set up a theatre review entitled Lola Montez in Bavaria, playing herself, an early example of the principle of being famous for being famous.

The review toured the east coast, before being taken west to San Francisco, where she married again (no awkward questions asked). But within two years she was off again, this time taking her review to Australia. In 1857 she came back to New York, living off her wealth, which she had taken surprisingly good care of, and earned more by reading from her memoirs and writing beauty tips in magazines, even – with remarkable hypocrisy – declaring her self a born-again Christian determined to save the souls of “fallen women”. But before she could complete a total role-reversal, she fell victim to a lung infection and died in 1860 at the age of just 39.

She is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Peter Millar is a journalist and author who has spent decades reporting from and living in Germany. ‘The Germans and Europe: A Personal Frontline History’, published by Arcadia Books, is out now.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks