The ManKind Project: How programmes, politics and pop culture are addressing toxic masculinity

In the wake of modern narratives surrounding sexual harassment, toxic masculinity and staggering male suicide rates, various sectors are attempting to rebalance what it means to ‘man up’

As I stood next to a man roaring with rage and wet with tears, in a community hall in deep west London, I thought – well, this is awkward. I don’t even like man-hugs, particularly those three-pat buddy jobs they do in Hollywood. Yet here was a real live male in distress, perilously close. Should I hug him, against the advice of my inner Brit?

Luckily, I didn’t need to decide. With the help of a convener, the man finally exhaled and came back “into the room”, to use the argot. And such a cathartic experience could have been anticipated, for I was participating in a meeting of the ManKind Project (MKP), known for their emotionally lacerating (and controversial) meetings.

They’re anonymous, and I promised not to disclose names and people as a condition of attendance, but a long-time member of MKP, 41-year-old cameraman Dan Kidner, explained his reasons for participating.

“The powerful element is being with other men who are sharing their feelings at such a deep level,” he says. “Before I experienced that, I thought it was only me who wasn’t coping and that everyone else was fine. It was a huge relief to realise that there was a community of men who are able to share their vulnerability.”

Dan came to MKP after a long, “lost” period which began at boarding school: an experience that promised to be “character forming” and which he found anything but, instead setting him up with a dysfunctional model of adult malehood.

“I’d say such institutions actually want to eradicate character,” he says. “They are fundamentally about hiding feelings. And where they encourage feelings, the only acceptable ones are rage and anger.”

Dan went on a several-year drinking jag to drown those feelings, finding himself in a classic drinker’s “shame-loop” of reward and remorse, before finding some kind of redemption with the MKP.

Sometimes known with generic simplicity as “The Work”, the MKP is one of a growing number of projects trying to rebalance masculinity. With its roots in the New Age self-development boom of the 1980s and 1990s – the era of Robert Bly’s breakthrough book Iron John – it has grown in popularity in the UK, and may even have found a new moment.

Such is the current public conversation about negative male behaviour – of violence, Weinstein and “toxic masculinity” – that the need for masculine change has gained extra urgency. Indeed, look around and one might say that disquiet about masculinity has become one of the big themes of the last few years.

This year’s “masculinist” hit was Robert Webb’s book How Not To Be A Boy, which explored the battle to reclaim his sensitivity in the antediluvian 1970s world of “manning up” and dressings down from a scary dad. Last year, Grayson Perry’s The Descent of Man continued the artist’s theme of maleness and emotional intelligence and this time, featured a scary stepdad.

The South Bank has just held its fourth Being A Man festival, featuring “poignant and necessary discussions around the challenges and pressures of masculine identity in our modern age”, and a recent play, 31 Hours, about four men who clean up after rail suicides, is described as “a journey through masculinity, mental health and messy aftermaths in modern Britain”.

Masculinity has become popular subject matter and not before time, says Nathan Roberts of abandofbrothers (ABOB), a group that works with men who have been involved in the business end of the criminal justice system.

“I’ve been involved in men's work for 15 years, but I think there’s a real upswell now,” says Roberts. “Back then there was ridicule.”

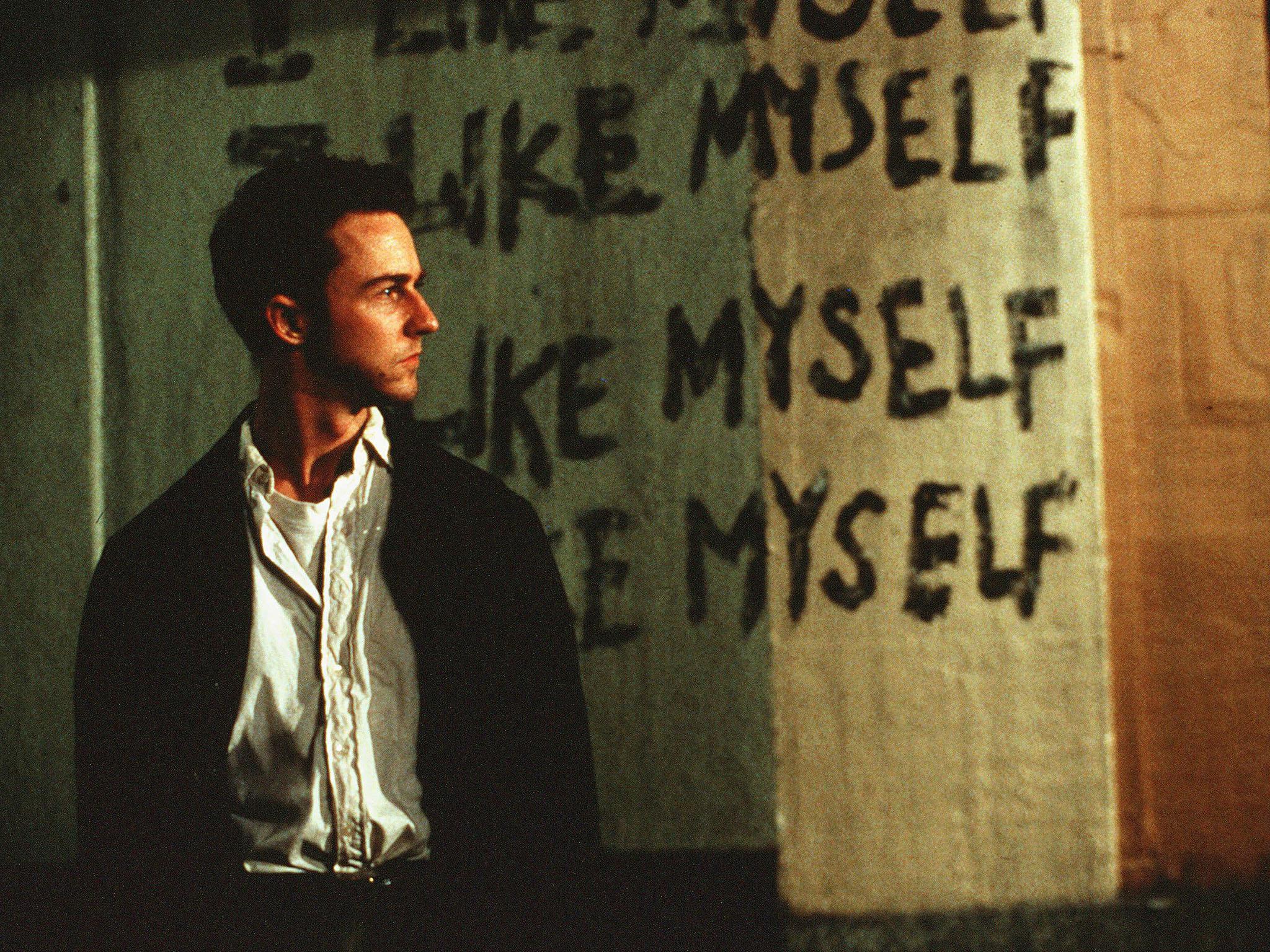

Now there’s a far greater interest and acceptance, helped by this autumn’s hit documentary The Work, where a group of therapists undertake a four-day programme with prisoners in Folsom Prison (the same institution of Johnny Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues”, which includes the classic line: “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die”).

It’s a rollercoaster watch, with men being held down on the floor in extremis, and it made my London experience look tame. But the goals are the same: the release and redemption that comes with the expression of pent-up emotions.

***

The MKP may be a touch “woo”. Its Native American-style greetings, and its cathartic rites-of-passage style, won’t be for everyone. But the idea that men need some kind of specialist salvation is going mainstream, and populating a new evidence base. There are other groups and experiences – a men’s weekend associated with MKP called The Adventure, and one called Noble Man, the latter facilitated by women.

Importantly, there is a growing political dimension, articulated by the Men and Boys Coalition, a network of 60 charities, academics, journalists and activists that launched late last year and which is committed to advocating the wellbeing of men and boys, by raising awareness of concerning issues, such as the fact that 60,000 fewer men now attend university than women.

Then there’s the apprehension of those slow-burn problems, such as the increasing numbers of boys growing up without fathers. The Coalition has several targeted affiliates, including male suicide prevention charity CALM (The Campaign Against Living Miserably), which has gained champions such as Gary Numan and Professor Green, and the Coalition’s founder, Mark Brooks, who has advocated for a Minister for Men for eight years – and is also chairman of a male domestic violence charity called the Mankind Initiative.

Brooks brings up a roster of male-skewed problems such as poor health, drinks and drug abuse, homelessness, employment and a suicide rate (a leading cause of death of men aged under 50) three times that of female suicide. He’s pleased that male advocacy has gained new validation.

“International Men’s Day has led the way. There seems to be a realisation that if we want to live in an inclusive society then we need to look at the specific issues facing men.”

It’s time to support men and boys when they are vulnerable, adds Brooks: to stop the “demonisation of a whole gender for the behaviour of a few”, and not to write off all masculinity as “toxic”. Elsewhere in public life we strive to dissociate collective responsibility from identity groups, he argues. So why not with men?

Is masculinism becoming another part of the shrill special-pleading competition that we call identity politics? There may be a touch of that. But male advocacy is not a zero-sum equation that denies other’s their rights, says Brooks. “In fact, it’s often been led by women. For example, (feminist comedian) Sarah Millican was involved this year.”

Perhaps this is because the idea of masculinism is moving from the margins to the centre. Rather than being stuck in “personal growth” individualism, it’s increasingly pitched as offering an overall benefit to society. Nathan Roberts of abandofbrothers, for example, sees the previous lack of focus on men as a kind of neglect that has stoked problems: “It has been a historic oversight in our culture to address fundamental male issues,” he says.

Those drivers of male despondency, such as the disintegration of traditional family units, weaker bonds between fathers and sons and the decline of community support structures, have been brewing for decades and have suffered a “vacuum of explanation”. Nor is some idea of “male privilege” much good for his clients: those ex-prisoners between 18 to 25 who go on courses to share their feelings without risk of scorn.

“The young men are part of the community of men, and it’s important that they are not talked down to,” says Roberts.

The benefit is lowered recidivism, he claims, which is why ABOB is expanding from its first group in Brighton to Crawley, Eastbourne, Haringey, Oxford and Cornwall. One alumnus of ABOB, Dean O’Brien, came from a scenario of burglaries, assault and drugs, and says that he “expressed a level of anger that I’ve never expressed before, but found out techniques for expressing in a way that wouldn’t hurt me, and wouldn’t hurt anyone else.”

There’s an element of this kind of men’s work that seems phoney and mock-tribal, with initiations and in-group language. Michael Boyle, the Jungian psychotherapist who is a key MKP facilitator, has calls the work “about meeting the unknown”, and frames it as a “heroic” search for meaning. A bit fairy-tale perhaps, but fathers of sons may appreciate Boyle’s notion that “men seem to learn mostly by imitation and through direct experience, rather than listening to what they are being told”. And that might not lead to polite scenarios.

At the MKP evening, I witnessed a man being physically sick as he released his pent-up emotions. It was alarming. How could such venting help with aspects like depression and suicide prevention? Kidner makes the case. “In one way or another, it probably saved my life,” he says. “I was very lost. Sadly, a cameraman I know took his life recently.”

And that really is “meeting the unknown”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks