Inside the world of the ‘death knock’

Social media, film and TV have helped cement the image of the heatless hack who’ll stop at nothing to get the human angle from the families of the bereaved – yet, particularly at local level, this is still an indispensable part of news-gathering

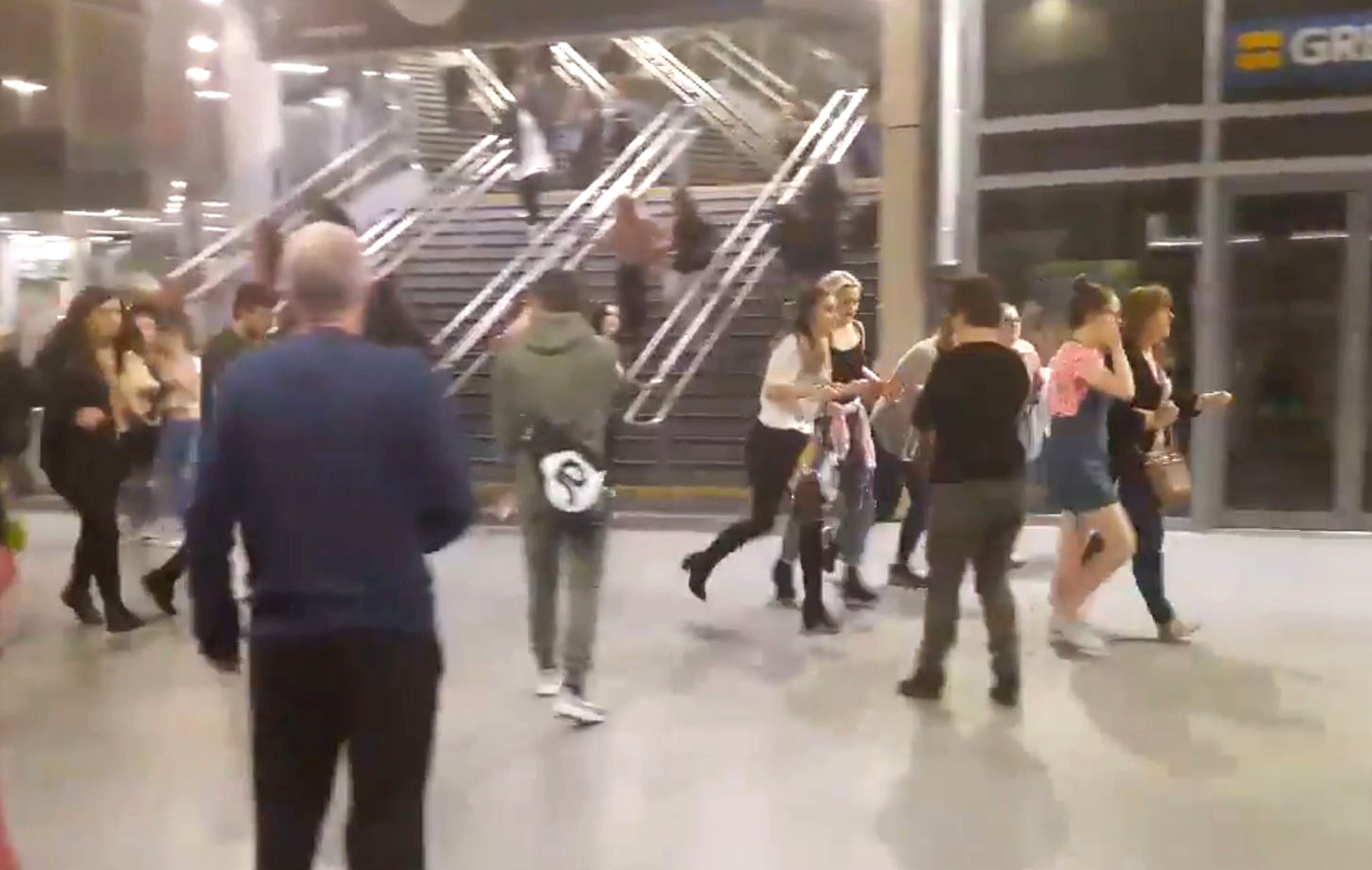

In the wake of the Manchester Arena (and now London Bridge) terrorist atrocities that have so far cost 29 lives, talk rather inevitably turned to the role and behaviour of the media, especially in relation to making contact, in the immediate aftermath of the bombing, with the families of those killed and injured.

Two particular posts on Twitter went viral; one from the brother of Martyn Hett, killed in the incident, and another from the account @DrEm_79.

In the former, Dan Hett tweeted: “I have dealt with 50+ journos online today. Two found my mobile number. This cunt found my house. I still don't know if my brother is alive.”

@DrEm_79’s thread of posts detailed how she was caught up in a terror incident four years ago and how the media, through trying to contact her via friends, family and her workplace, “made the trauma much worse”. Both postings were shared around more than 11,500 times each.

This is the face of journalism that most people find unpalatable. We have a picture built up in our heads of the heartless, stop-at-nothing, foot-in-the-door hack who hounds innocent, grieving people, an image given fresh life every time a TV crime drama or soap screenwriter pens a scene featuring a mob of baying journalists, or a conniving reporter who harangues people in the street and will stoop to any depths to obtain their story by fair means or foul.

Those scenes will have journalists, particularly local newspaper reporters, groaning up and down the land, because by and large they just don’t happen. Soaps are the worst offenders; the last season of Broadchurch more or less got it right.

But that’s not to say journalists don’t try to contact people in the wake of tragedy. They have to. That’s what they’re paid for. It’s just not a pretty part of the job, and it’s certainly not the whole of the job, and it might surprise you that often it’s actually welcomed by people on the receiving end.

The experiences of @DrEm_79 and Dan Hett were, of course, awful for them, though Hett did later tell the Guardian that he regretted the tweet, while still being frustrated that he was constantly being contacted when he was waiting for official news from the police.

However, there’s something of a dichotomy at work here. When something like Manchester happens, we want information. We want news. We want the human face of the tragedy. We consume and share and debate it when we get it, but we also take issue with the way this information is delivered to us.

Manchester, of course, is an exception; an atrocity that garnered attention on a worldwide scale. But this information gathering is going on at a much more localised and less widespread level by journalists every day of the week. Allow me to shed some light on the shadowy world of the “death knock” – two words to cause the heart of any local reporter up and down the land to sink to their boots.

It’s quite as grim as it sounds. Upon receiving the news of a death – from a road accident, a murder, a drowning, a drugs overdose, pretty much anything you can think of – a reporter is despatched to knock on the door of the grieving family and come back with the information drilled into every trainee journalist from day one: who, what, when, where, why, how. Your notebook must be full of emotive, heart-rending quotes. There must be a photograph of the deceased. It will probably make the front page.

It’s a rare reporter who actually enjoys death knocks, and I have known a handful. For most – certainly for me when I was a local newspaper journalist, a job I did for a quarter of a century – it’s a hateful task. I frequently walked around the block three times before plucking up courage to knock on a door. Sometimes I would pause, my finger hovering above a doorbell, and consider just going back to the office and saying no one was in. My guts would churn, not knowing what reception I would get.

And there’s the rub. If we knew for certain we were going to get short-shrift, be called cunts and have our methods ridiculed on social media, then we’d always say there was no one in. We’d not even bother going out in the first place. The death knock would have died out long ago.

But that’s not always the case. In fact, from my experience, it was quite rarely the case. Take a look at your local newspaper sometime. Over any given week, there’ll be at least one story that is the result of a death knock. Local journalists keep knocking on doors, and people keep letting them in. But why, when we seem to consider it to be such an abhorrent practice?

Firstly, let’s look at the rules around death knocks. There are guidelines, laid down in the Independent Press Standards Organisation’s (IPSO) Editor’s Code of Practice. On intrusion into grief or shock, the code states: “In cases involving personal grief or shock, enquiries and approaches must be made with sympathy and discretion and publication handled sensitively.”

On harassment, it says that journalists “must not persist in questioning, telephoning, pursuing or photographing individuals once asked to desist; nor remain on property when asked to leave and must not follow them. If requested, they must identify themselves and whom they represent.”

In other words, if a journalist knocks on your door and you tell them to go away, they should. If they shout at you in the street asking for details of the tragedy that’s befallen your family, that’s not approaching with sympathy and discretion. You’d be within your rights to complain about their behaviour to IPSO.

But outside of TV soaps and the sometimes rabid pack mentality that the press gets around celebrities or disgraced politicians, that sort of thing rarely happens. A case in point: I well remember my very first death knock. A young man in his early twenties had died suddenly of a brain haemorrhage while at work. I was sent to knock on his family’s door. I was only 19 myself, and had no experience of death.

His mother answered the door. I explained who I was and why I was there. She wasn’t sure, and said she’d have to consult with her dead son’s father, who was out. She said I’d better come back later.

I returned in the afternoon. The father was still out and she hadn’t been able to speak to him. She suggested I try in the evening. Later that day, I knocked on the door for the third time. Was I remiss in doing so? Should I have just left it? Had the mother said no from the off, I would have done. But on the third visit, the father was home, they’d discussed it, and they invited me in. I spent an hour with them, talking about their son, what he was like, where he went to school, his hobbies, his interests, the fact that he’d just got engaged. I left with a large portrait of him that his father took from the wall over the fireplace.

The story appeared on the front page the next day. I took back the portrait, and received the profuse thanks of the family, who had felt that seeing their son’s life celebrated in their local newspaper had helped them to cope in some way.

On another occasion I attended the home of a young man who’d died in a car accident. I walked up and down the street. I considered going back to the office and saying there was no one in. This, it turned out, was a prime example of why that couldn’t be done. His mum opened the door and invited me in. “I was wondering when someone would come,” she said, showing me to the kitchen where on the table were piled three albums of photographs of her son for me to take my pick from. “I was worried you didn’t want to put him in the paper.”

Of course, not everyone needs or wants the closure of an obituary for their loved one. I have had doors slammed in my face, I have been told politely that the family is not interested. I was once chased down the street by the grieving father of a teenager who had stolen a motorcycle and wrapped it and himself around a tree. But you never know until you knock on that door.

The advent of social media has perhaps made it easier for journalists to contact grieving relatives without resorting to the death knock. That can have pros and cons for both sides… people can feel hounded on social media, especially if many journalists try to get their attention in a short space of time. People might say no more readily online than if a reporter is on their doorstep.

In those far-off pre-internet days when I started work, I spent some time under an editorial regime that was, to put it mildly, death obsessed. Someone would trawl the death notices in each day’s paper and send out reporters to anyone that was, say, under 40, on the grounds that there must be a human interest story there. I regularly did up to four knocks in a single day.

Sometimes you only had a name and a street to go on. You would have to start at one end of a road and knock on doors until you hit the right house. Often, the reporter wouldn’t even know what had led to the person’s death.

Sent out to the address of a man in his twenties one time, I was invited in by his mother. Over tea and biscuits we discussed his life, while I was still unaware of the cause of death. This was very early in my career, I can have been no more than 20. The mother told me that he was a teacher. He taught music. Oh, I wondered, at a local school? She said, “He was peripatetic.”

“I’m sorry,” said young, naive, unworldly me. “Is that what he died from?”

“No,” she answered, somewhat surprised. “It means he travelled from school to school.”

When you do enough death knocks, you develop a streak of gallows humour. It’s perhaps unavoidable. No one cares about the journalists in these situations, and why would they? But repeated death knocks can take their toll, can cause some measure of trauma, and there’s usually very little done about that in news organisations.

So why do newspapers do it? For the human interest stories, of course. Tragedies sell papers, get clicks. But also because it can be a form of public service, done right – the number of calls and notes journalists get thanking them for the results of their death knocks are testimony to that.

For every Twitter thread complaining about journalistic practices and harassment, there will be many more people who felt that they were perhaps allowed some closure through speaking to a reporter. My heart goes out to Dan Hett and @DrEm_79 for what they went through… I wouldn’t like to be bombarded by journalists in my hour of suffering any more than they did.

On the other hand, I have some sympathy with the reporters who were sent out to make contact. They could no more refuse than they could say no to any other part of the job, from reporting on a coffee morning to covering a council committee.

Perhaps there will come a time when journalists are no longer despatched to speak to the bereaved in the wake of tragedies large and global or small and personal, but as long as there is an appetite for information from the general public, I hugely doubt that will happen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments