Lack of perspective: Why journalists should be haunted by a history of blinkered reporting

When news of the Holocaust first hit papers, it didn't make the front page – now, writers report impending wars that never materialise. Both approaches are dangerous, says Robert Fisk

There’s an old saw that journalists write the first draft of history. I used to think this was true. If the journalists of the First World War wrote fiction from the generals’ chateaux, the reporters of 1939-45 were different. They were at Dunkirk and watched the Battle of Britain. They landed on D-Day. Even the Russians had journalists on their front lines. Read Vasily Grossman’s accounts of the battles of Stalingrad and Berlin. As a schoolboy, I used to listen to my BBC recording of Richard Dimbleby in a Lancaster bomber in 1943, approaching the Hamburg firestorm. “A great white basin of light in the sky,” he called it. Or read Richard Hillary’s The Last Enemy.

Here he is, his face terribly burnt in his crashing Spitfire during the Battle of Britain, going to the rescue of a dying woman and her child in the London Blitz: “It was her feet that we saw first, and … now we worked with a sort of frenzy, like prospectors, at the first glint of gold … We got the child out first. It was passed back carefully and with an odd sort of reverence by the warden, but it was dead … The woman who lay there looked middle-aged. She lay on her back and her eyes were closed … I was at the head of the bed, and looking down into that tired, blood-streaked, work-worn face I had a sense of complete unreality.” Hillary offered the woman brandy and she “reached out her arms instinctively for the child ... Then she started to weep. Quite soundlessly, and with no sobbing, the tears were running down her cheeks when she lifted her eyes to mine. ‘Thank you, sir,’ she said, and took my hand in hers. And then, looking at me again, she said after a pause, ‘I see they got you too.’”

Dimbleby, of course, was a reporter. Grossman was both a writer and journalist and – from the Soviet point of view – a propagandist. Hillary wasn’t a journalist at all. He was a fighter pilot who knew how to write. But Dimbleby’s “basin of white light”, an emblematic bowl of fire, and Hillary’s startling imagery – the rescuers for whom the woman becomes a “glint of gold”, the air raid warden who shows an “odd sort of reverence” before we hear that the child is dead, and the “work-worn” woman’s deathly observation that “they got you too” – shows how the reporter and the warrior can write in the same language.

It was not always so. In the First World War, poets – Blunden, Sassoon, Kettle, Owen of course – wrote in a language far more comprehensible and contemporary than the great and now forgotten correspondents in France. Was the Second World War, I often ask myself, the first and last time that soldiers and reporters complemented each other as witnesses to war – although we must remember that British correspondents wore uniform – and could reflect each other’s imaginative power? Ed Murrow’s “London Calling” broadcasts from the Blitz and his colleague William Shirer’s reporting from Berlin had much in common with Hillary’s prose.

Vietnam did produce reporters and soldiers who could out-write each other, but some time after that – in the later stages of the Northern Ireland war, perhaps, or in the constant bloodbaths of the Middle East – I suspect we lost something even more important: our sense of perspective. In the first Gulf War of 1991 (in reality, it was the second Gulf war, since the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq had earned that sobriquet, easily forgotten since it involved no western armies) many of the journalists I saw wore some form of military costume while quite a lot of soldiers I talked to wanted to write newspaper articles. All the journalists, it seemed, wanted to be soldiers, while the real military men secretly wanted to be reporters.

Was this because we all had laptops, because we were entering the world of emails and websites, Facebooks and apps, that we needed no longer to read history books – for Mr Google would, surely, supply all the “background” we needed – and because, so infinite were our communications, that we no longer needed to search for a “narrative” (a word I have come to loathe) because a gluey mass of CNN, Fox, The New York Times, The Daily Telegraph, the BBC and what-have-you allowed us to identify the good guys from the bad guys? They would decide how to differentiate the dictatorial Sisis from the dictatorial Assads, the “moderate” head-chopping Saudis from the “extremist” string-them-up Iranians, “rogue-state” Russia from the democratic and freedom loving (if highly corrupted) Ukraine. And so on.

What I fear is the idea that as long as we get the general drift of what politicians, editors and ‘experts’ think, we can more or less batter away on our laptop keyboard to our heart’s content with little worry about whether our pre-conceived version of history/myth turns out to be true or false

Sometimes, we muddled this up a bit. Sisi could lock up 60,000 political prisoners and his police thugs could torture to death an Italian PhD student (being an Italian resident of Britain, he didn’t count for much anyway), while Assad could lock up slightly fewer political opponents (probably killing a lot more of them). And the Saudis could get away with marketing their ruthless new dictator, Mohammad bin Salman, spearhead of the bloody Yemen debacle, as a western-style, progressive would-be king – good old “MbS” – who would “reclaim Islam for its truly open and pluralistic character” (courtesy Thomas Friedman of The New York Times) and get “the rules and regulations right in Saudi Arabia” (courtesy Friedman and the NYT again). And as Friedman quoth, “only a fool would bet against him”. Which is what Jamal Khashoggi did – and look what happened to him.

I don’t quite agree with John Simpson that journalism is “a form of escapology”, although this might account for our lack of perspective. Antony Beevor’s observation – that reporting is “instant” while history is “reflective” – makes more sense. But what I have in mind – and what I fear – is the idea that as long as we get the general drift of what politicians, editors and “experts” think, and as long as we absorb their definition of the probable, the definite and the unimpeachably correct, we can more or less batter away on our laptop keyboard to our heart’s content with little worry about whether our pre-conceived version of history/myth turns out to be true or false.

Cliches are welcome. Dispatches that question or challenge the accepted storyline are suspect, dubious, out-of-line, biased or even embarrassing. I’ve always believed that when a European or American foreign correspondent on the internet in, say, Moscow or Beijing or Cape Town could write an identical story if he or she were in Wisconsin or County Mayo, then they might as well go home and live in London or New York. My old chum Peter McKay – when we were on the Sunday Express together – would claim that journalism was a craft rather than a profession; which is true, up to a point. The lower-middle artisan class of the late 19th century could build a railway locomotive in Darlington, Delhi or Pittsburgh and it would look pretty much the same. But we don’t all have to write identical dispatches.

I’ve always believed that the best way to report a story is to write it as if it’s a letter to a friend. “Here’s what I saw”. “This is what they said”. “This is the recent record of events I witnessed”. And “here’s what I think/suspect or” (let us be frank) “am outraged about”. In other words, our job is not to write for sub-editors on a news desk or editors or MPs or politicians – how many times have I heard my colleagues say that they have to call the office “to see what the desk wants” – but to write for the readers. They are the “friends” we should be thinking of, even if some might describe themselves as our enemies. And we should remember that these “friends” are often (usually?) better read and educated than we are.

And it’s interesting that whenever I’m giving talks abroad – when I actually meet the readers who peruse the words that spark off our anvils of literature – they do seem to have questions quite different from the “experts” who expect us to agree with their every politically correct view. Very often, these readers want to talk about history. When we write about Egypt, why don’t we bring Britain’s colonial rule into our stories, its crushing of free debate after the First World War, its exile of the great Egyptian democrats of the early 20th century? Why don’t we recall the 18th century love affair between the House of Saud and the crazed Wahabi sect when we report on Saudi Arabia? Or the famine of the Levant when we write about Lebanon? Or French rule in Syria when we reflect upon the current Syrian war.

Yes, of course we mention these historical facts, but more as an addendum to our reporting – a sidebar, as we say in the trade – rather than what this history represents: a part of the life of everyone living in these countries whose actions and decisions and wars often derive, directly, from these events. A Palestinian in the slums of Lebanon or the West Bank can often tell reporters more about the Balfour Declaration than journalists know themselves. After all, the Palestinians live Balfour’s 1917 support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. They breathe it today in the dust of their refugee camps. If only we arrived on assignments not with a clippings file or print-outs of recent articles but two or three history books, to be read rather than surfed. Readers know this literature rather well. We often don’t

814

The actual death toll of the Luftwaffe’s 1940 bombing of Rotterdam, first put at 30,000

But not the least of readers’ requests is a demand for perspective. Why do we keep warning of the dangers of wars that never actually take place? And if politicians do this – presidents, prime ministers, UN secretary generals – why do we have to imitate them in prose? And – an almost equally important question, this – where on earth do we get our figures from, our statistics of death and mortality, our scorecard of killings?

And here, perhaps – since we always rage (or should rage) against the power of exaggeration – we should again go back to the Second World War. On 14 May 1940, German and Dutch intermediaries began negotiations for the surrender of Rotterdam. Nazi troops had invaded Holland four days earlier. But the Luftwaffe attacked the city. It matters little that at the last minute, the Germans tried to stop the bomber fleet and mostly failed. The centre of the great and historic port was laid waste and the Dutch foreign minister announced a death toll of between 25,000 and 30,000 civilians. Here, clearly, was the proof of Hitler’s barbarism. This is how it was interpreted by the allied powers, although the far crueller destruction of Warsaw eight months earlier should have left no doubt about Hitler’s brutality.

And by the time the war ended and the previously occupied powers rightly demanded justice at Nuremberg, statistics didn’t matter so much. But the Rotterdam figure of up to 30,000 dead began to crumble. In all, only 814 civilians, the Dutch agreed, had been killed in the infamous Nazi raid. The 1940 bombing was, of course, still a war crime. The mass murder of more than 800 men, women and children was surely a crime against humanity in any court of justice – although, given the titanic slaughter across other wartime nations, the exact figure for Rotterdam hardly mattered. Yet the original 30,000 was remembered, and even found its way into the 1953 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. It was wrong.

Now let us turn to another Second World War statistic which was infinitely more terrible and mattered very much – because it was absolutely true – but which was regarded at the time as so unspeakable, so outrageous, so close to the inferno of our minds that its reality (a burning inferno indeed) could not be grasped, and was thus “incredible” in the original meaning of the word. For on 25 July 1942, The Daily Telegraph – a beacon of accuracy in those days – headlined a story: “Germans murder 700,000 Jews in Poland”.

I suspect we journalists are so haunted by our subjugation of history that we will always choose the highest death toll, the greatest massacre estimate, the most appalling level of atrocity when confronted with crimes against humanity, lest we get it wrong again

The information was supplied by a Jewish socialist member of the Polish government-in-exile, Szmul Zygielbojm (and since readers often ask about pronunciation, we would probably transliterate his name as “Shmool Zeegielboym”). He had many contacts in occupied Poland and the details of the fate of the Jews were smuggled to him in London on microfilm hidden inside a key. The Daily Telegraph reported that mobile gas chambers were being used for industrialised murder and that around 1,000 Jews were being killed each day: “Children in orphanages, pensioners in almshouses and the sick in hospitals have been shot. In many places, Jews were deported to ‘unknown destinations’ and killed in neighbouring woods ... In Vilna 50,000 Jews were murdered in November [1941]. The total number slaughtered in this district and around Lithuanian Kovno is 300,000”.

In Rovne alone, the paper reported, 15,000 Jews had been shot in three days and nights. And so, in its six-page wartime edition in July 1942, The Daily Telegraph reported what it called the “greatest massacre in the world’s history” – on page five! The Telegraph itself retold the story of its “scoop-that-wasn’t” in 2015. The figures and the details were spot-on correct. But the crime – so monstrous that Churchill had already referred to it as “a crime without a name” – gained, as they say, no “traction”. This was the first real published account of what would become known as the Jewish Holocaust. But it didn’t deserve the front page headline. Not because it wasn’t true. Not because the source might be doubted. But because the report was unimaginable. Besides, hadn’t the British publicised all those fake stories about German atrocities in Belgium in 1914, of women raped and nuns crucified on church doors? And these reports of “Hun” barbarism at the start of the First World War turned out to be fiction – actually not quite fiction because German troops did murder Belgian civilian men and women in 1914, but that’s another story.

In any event, by this stage of the Second World War, Zygielbojm’s wife Manya and their son Tuvia were in the Warsaw Ghetto where both died in the destruction of the ghetto in 1943. Broken by this terrible news and the public’s indifference to his reporting of the mass murders, Zygielbojm took poison. The murders were the responsibility of the Nazis, he wrote, but humanity had “not taken any real steps to halt this crime”. In crude terms, I suppose, the “desk” didn’t want the story. After all, they hadn’t seen the story anywhere else. And this lesson in journalistic history should haunt us today. Check for exaggeration in Rotterdam in case it influences the course of the war – and there is evidence it hardened many hearts in Britain – but for heaven’s sake, when the facts are clear, checked, undeniable (except by the Nazis) and obviously a turning point in history, indeed “the greatest massacre in world history”, we must publish and be damned.

The problem today, I suspect, is that we journalists are so haunted by our subjugation of history – which is exactly what it was – that we will always choose the highest death toll, the greatest massacre estimate, the most appalling level of atrocity when confronted with crimes against humanity, lest we get it wrong again. This is entirely understandable. It is also very dangerous. Because if all dictators are to be compared to Hitler – as indeed they usually are in the Middle East – then our historical perspective has been destroyed. Eden claimed that Nasser was the Mussolini of the Nile, US and British politicians renamed Saddam the Hitler of the Tigris, and the Israelis and the Saudis now regularly compare the Iranians to the Nazis. And not only are our enemies evil; we must obviously be squeaky-clean ourselves. The British and Americans could thus never be guilty of aggression or war crimes – in Iraq, for example, or Vietnam – nor could the Israelis or Saudis, in Gaza or Yemen (or Istanbul) be guilty of murder.

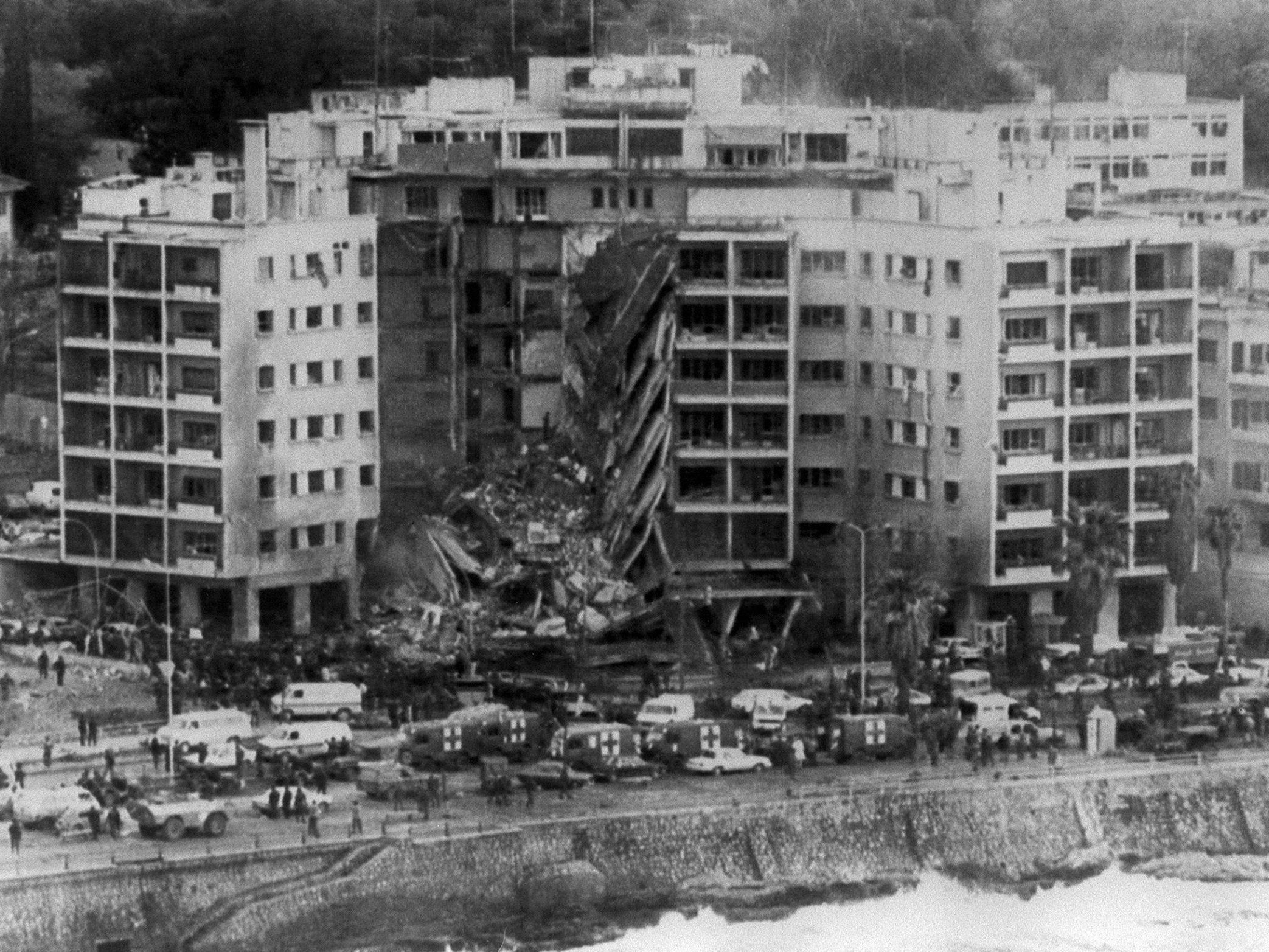

This not only distorts our own vision, but allows those who read our reports to evince ever more doubt about our own truth-telling. Take an example that emerged only a few months ago in Lebanon. A young Lebanese NGO – and NGOs are becoming scholars in advanced casualty statistics these days – announced in the local Beirut papers that he proposed to construct a memorial to all the dead of the 1975-90 Lebanese civil war. And he said these amounted to 200,000. I was stunned. I lived through almost the entire war in Lebanon and, with colleagues on the AP, spent literally days of my life cataloguing the numbers of men, women, children, soldiers and fighters and mass murderers, politicians and prime ministers killed in that conflict. We went through old police and civil defence files, gravediggers’ notes and hospital records. Give or take a few thousand – yes, alas, we must say that – our total came to 150,000 dead. So whence came the extra 50,000 souls just created by our worthy NGO? Or – if real, and therefore dead – who killed them? No matter that the whole memorial idea was ridiculous. It would take at least a century in Lebanon before relatives of the dead can decide whether the names should be alphabetical, whether the Lebanese will allow Palestinian or Syrian names on the monument or whether the Muslims will allow Israeli names or whether UN forces or American or French forces of 1983 Beirut would want their soldiers listed among the killers of Lebanon.

But it was the 50,000 that caught my attention. Why was it so necessary to exaggerate the civil war dead? To create a bigger memorial? To shock the jaded reader? Or simply to “up” the death toll in order to make the “story” more “alive”? And even if we could not quite trust the new figure, we could always report that the civil war cost “up to 200,000 lives”.

Take Syria. How many innocents have been killed in this frightful eight-year conflict? Apart from the UN and the Arab League, almost all figures are compiled or collected or devised by opposition groups. The Syrian Network for Human Rights says that 222,114 civilians have died since March 2011, most of them (198,152) at the hands of Syrian government forces, at least 14,000 by rebel or “other” forces. The “Syrian Observatory for Human Rights” says 110,687 civilians have been killed since March 2011, the vast majority of them (85,114) by Syrian government forces, more than 12,000 by Isis or other rebel groups. The SNHR’s first figure, however, is almost double the same number of dead civilians listed by the SOHR. Furthermore, the “observatory” – an odd word which has yet to be explained – agrees that it has included in its civilian dead those citizens who later carried weapons during the war. In other words, armed men.

157,208

Discrepancy in estimates of Syrian war death toll

Total estimates for all dead vary in an almost fantastical way – between 364,792 and 522,000. The UN claimed the estimated total figure for all dead in 2016 was 400,000. But before we choose which number to choose – or which is the highest figure to use in our reports – how can we possibly account for the estimated 250,000 civilians trapped in the eastern Aleppo enclave before the Syrian army captured it in 2016, and the actual number of perhaps 150,000 who left the city in buses to go to Idlib or other areas of Syria or who moved to government-controlled areas after the battle was over? What happened to the other 100,000?

This does not mean that repeated reports of barrel bombs, chemical weapons use or executions are untrue. It does not mean that the dead cannot be in the tens of thousands or the hundreds of thousands. What it does mean is that we need to exercise far more scepticism over just how the atrocity figures are compiled. If a number is exact – the observatory’s 110,687 total civilian dead, for example – we must ask how this is possible. Can it really be sure it has every single death listed so carefully – amid the wars, war crimes, mass slaughter – that the toll isn’t 110,686 or 109,688? And are we really supposed to believe figures such as 400,000 dead – to the very last zero? Interestingly, the International Red Cross, who dwell amid laws about the illegality of war, usually prefers not to mention a number.

There’s also a new expression which has gently moved into the common parlance of our reporting of death. It is the “death range”. Between 400,000 or 450,000, for example. By chance, some months ago, I flew from the Gulf to Lebanon and found in my Qatar newspaper a total figure for Syria’s death toll as 450,000. By the time I picked up the Beirut press, its total – in a report for the same day – was “more than 350,000”. So, like Aleppo, we were already 100,000 dead – or living – souls out of sync.

Numbers – however ‘legit’ to reporters in New York, London or the Middle East – can kill. And people suffer even if we report forthcoming wars that never actually take place.

Amnesty last year published a carefully researched file on extrajudicial killings in Syria’s Sednaya prison, estimated at between 5,000 and 13,000 executions between 2011 and 2015. The contents were chilling – bodies tumbling out of the back of a truck on a traffic ramp, for example, when the corpses were taken for post-mortem documents – but the statistics were distressing for their very vagueness. Which was it, for heaven’s sake? Five thousand or thirteen thousand? Again, it must be said at once that 1,000 such executions in Sednaya – 500 or even 100 – must constitute a crime against humanity. The 814 victims of the Rotterdam bombing in 1940 were no less dead – and no less cruelly murdered by the Nazis – because the other 29,186 citizens who were said to have been killed were fortunately still alive. But once we play with “between 5,000 and 13,000”, an unhappy correlation creeps into the Amnesty report. To be on the safe side of statistics, for example, the report might have said “at least 5,000”. But by topping it up to 13,000, it invited all media headlines to claim – as they inevitably did claim – that “up to 13,000” men may have been hanged, more than 62 at a time. I recall having lunch the day after the Amnesty report was published with a Lebanese friend who immediately consulted the pocket calculator on her mobile to work out the number of hangings per week. “More than 60,” she said. Correct – and she had immediately adopted the higher figure.

Numbers – however ‘legit’ to reporters in New York, London or the Middle East – can kill. And people suffer even if we report forthcoming wars that never actually take place

There’s no point, of course, in expecting the warlords or dictators or generals to come up with death tolls. US generals “don’t do bodies” – “enemy” bodies, that is – not in Iraq, not in Afghanistan, definitely not in Mosul. And the Syrians no more attempt to calculate the innocents killed in their war than the Saudis tot up the number of children killed by their airstrikes in Yemen. Yet since culpability increases with every digit, those who uniquely blame the Saudis or the Syrians or the west for the death of innocents will always pitch for the figure higher. But these figures – and they seem to be used more in reports written far from the front lines – can have a dark meaning.

How are Syrian (Shiite) Alawites to react, for instance, when they read a pro-opposition website in 2017 which told them that 150,000 of their fighting young men – out of a total of perhaps 250,000 in the country – have been killed? Their deaths in the ranks of the army and government militias – Assad, of course, is himself an Alawite – is probably disproportionate. But most of the Syrian army are Sunni Muslims. And such a figure can worm its way into the future telling of Syria’s tragedy, to reinforce Alawite victimhood. And for those convinced that exaggeration of casualty statistics has no real effect on the survivors of conflict – or merely “covers” the possibility that the civilians have died in larger numbers than we thought – history suggests otherwise.

In Ireland, a place where the number of sectarian killings has always acquired deep political significance, there is a poignant example of this game which should be studied by anyone floating new casualty tolls for Syria or Iraq or anywhere else in the Middle East. On 23 September 1641, Gaelic Irish Catholics of Ulster, dispossessed by the Protestant colonisation of the province, staged a blood-soaked “intifada” – and yes, the Arabic word might be appropriate these days – for the return of their confiscated lands. The savagery was especially appalling in Ulster, where 17th century Catholic atrocities have remained, even now, a political folk memory for the descendants of the Protestant victims.

There are today 32 volumes of evidence carefully archived at Trinity College in Dublin of the crimes against humanity committed against those Protestants, many written with the same horror and indignation which greeted the reported use of chemical weapons in Syria more than 370 years later. In Portadown, for example, the books of evidence at Trinity describe how around 100 Protestant men, women and children were dragged from their homes, stripped naked and thrown from the parapet of a bridge – after which they were either drowned or shot or bludgeoned to death. “Some of the [Catholic] Irish,” wrote the historian Robert Kee, “even took to boats and bashed them with oars as they floundered in the waters”. There may be exaggerations here, but such killings did happen.

Protestants were burned alive. And for those with the courage to read it, here is the deposition of Elizabeth Price of Armagh: “And a great number of other Protestants, principally women and children, whom the [Catholic] rebels would take, they pricked and stabbed with their pitchforks, skeans [knives] and swords and would slash, mangle and cut them in their heads and breasts, faces, and hands and other parts of their bodies … but leave them wallowing in their blood to languish and starve them to death.” Other evidence tells how Grizell Maxwell, the Protestant wife of an army officer, was slaughtered in childbirth – for proof, we know that the details came from her brother-in-law, the Reverend Robert Maxwell, rector of Finnane in County Armagh.

But some of the evidence was sworn many years after the events – suspect indeed – and it seems that atrocities were committed in fury rather than premeditation. No excuse. Sectarian killing is sectarian killing. But the death toll – and here the future ghost of Syria moves into our vision – suggested by one contemporary historian for Protestant victims was 150,000. Horrific indeed – but this was more than the entire Protestant population of Ireland at the time. Today, historians suggest that perhaps 12,000 Protestants were murdered or died of wounds. The figure had thus been exaggerated by 12 and a half times.

But to again quote Robert Kee, whose television series on Irish history became legendary in the 1980s, “exaggerated versions of the atrocities have been as important as the reality in conditioning later attitudes in Northern Ireland. There is in the Northern Ireland historical subconscious no limit at all to the horrors that might have been or might still be inflicted on them … Northern Ireland Protestant attitudes today are still conditioned by the fact that they are a minority in the whole of Ireland.” To this very day, the massacre at Portadown remains portrayed on the banners carried by Orangemen through the city of Belfast.

Tell that to the young NGO who wants to erect a monument to Lebanon’s “200,000” civil war dead. Or to those who claim that 450,000 is – or probably is, or may be, or should be – the total number of victims in Syria. Or to those who report these figures without referring to history or the numerical lessons of history or to the willful and grotesque miscalculations of the past. Numbers – however “legit” to reporters in New York, London or the Middle East – can kill. And people suffer even if we report forthcoming wars that never actually take place – or certainly not when and where we say they are going to take place.

Remember how just a few weeks ago, Israel and Iran were supposedly about to go to war? All this, apparently, because the Israelis claimed the Iranians had fired missiles at their positions in the occupied Syrian Golan Heights. No matter that the missiles may have been fired by the Syrian army in retaliation for Israeli airstrikes on Syrian military positions. No matter that the constantly-evoked “20,000” Iranian military personnel are closer to 2,000 in total. The Middle East was, we were told, closer to war – or “all-out war”, though I have yet to understand the difference – than it had been since 1973. War clouds were gathering. But then? Poof. The war clouds receded although we didn’t attempt to tell our readers why – because, I suspect, both the Israelis and the Iranians had wanted to reestablish their involvement in the Syrian war. The war clouds mysteriously dispersed and we said no more about it.

It’s not just about cliches or easy, lazy statistics. It is about history and precedent, about the need to write with power so that the journalist, the soldier and the refugee speak the same language

Even more recently, we were told that there was to be an “apocalypse”, a “massacre”, an “ethnic cleansing” in Idlib province, where the last Islamist remnants of Syria’s rebel army was surrounded. A hundred thousand Syrian soldiers had arrived to take the battlefield – the Syrians themselves said this. But when I toured the Syrian front lines around the entire province of Idlib – I spent days doing this in back-breaking journeys over bad roads, so I guess I have my own little grudge – I saw a total of 200 soldiers in a mountain base, seven tanks, five helicopters, a lot of checkpoints and a herd of camels. This was no army on the brink of war. Where were the ammunition columns, the convoys, the thousands of tents strewn across the desert? Zilch. There was going to be no battle for Idlib. Not now, at any rate. But the stories funnelled on, from New York, London, even Damascus. War clouds went on looming. There was no way to stop this stuff – any more than there is a rational way of cooling the overheated casualty figures. Only a Russian-Turkish agreement sent the war clouds away. Maybe they will return. Deadlines for rebel withdrawals have already passed. And there may be another war which will lead, be sure of this, to another Syrian regime victory at which point hostilities will end, and we’ll all tot up – or forget if they prove to be wrong – the casualty figures and the refugee figures. And media stories will be written of how eventually – yes, be sure of this too – “the guns fell silent”.

No, it’s not just about cliches or easy, lazy statistics. It is about history and precedent, about the need to write with power so that the journalist, the soldier and the refugee speak, if you will, the same language. And it’s about remembering, always, that the reader probably knows more than us, has read more, studied more, thought more – and wants something better than our football-game coverage. What we are reporting is history. But we shouldn’t forget what went before.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks