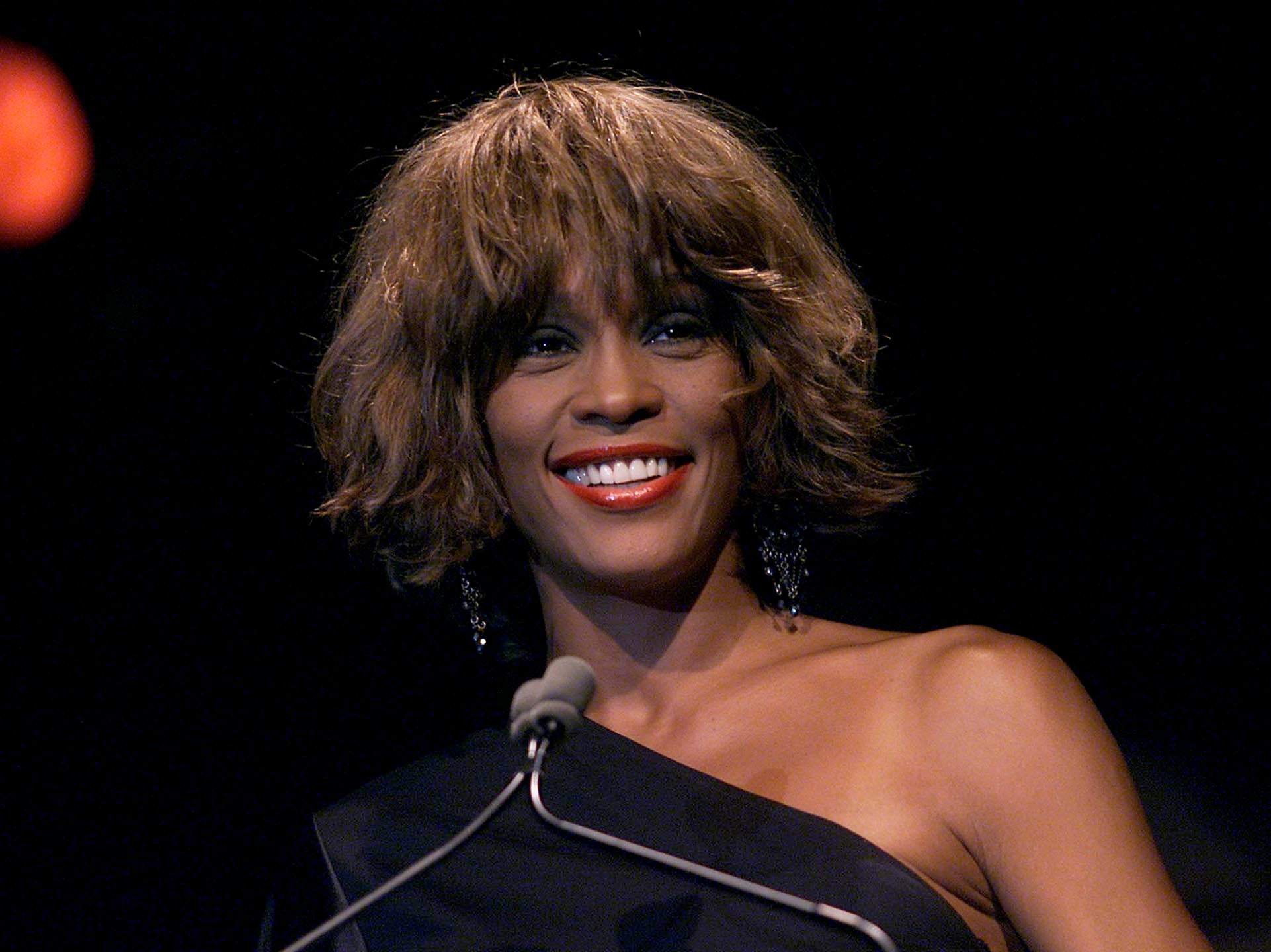

Whitney Houston and Clive Davis: An unfinished story

Producer Clive Davis never liked being called a Svengali to singer Whitney Houston – he thought it sounded slithery. But, Jacob Bernstein questions, how else to describe the pair’s relationship?

Downstairs at the Beverly Hilton Hotel on 11 February, 2012, black cars delivered Serena Williams, Britney Spears and Gayle King to Clive Davis’s 2012 Grammys party. Upstairs in Room 434, the coroner’s office tended to the body of his biggest star, Whitney Houston. She had been found dead in the bathtub that afternoon. Police investigators removed empty bottles of liquor while the wails of her daughter, Bobbi Kristina Brown, echoed down the hall.

Chaka Khan later went on CNN to call Davis’s decision to not cancel his party an act of “complete insanity.”

“She was a lonely voice,” he said of that criticism a few weeks ago, in his corner office at Sony’s new headquarters near Madison Square Park in New York.

Davis is a legend in the music business. He signed Janis Joplin in 1967, turned Barry Manilow into a star in 1975 and orchestrated the reinvention of Aretha Franklin in 1980. But his relationship to Houston cemented his reputation as a first-rate hit maker and packager of talent.

The albums she released between 1985 and 1998, contained 11 Billboard No 1 hits and sold more than 50 million copies in the United States. More than serving simply as a label head, he matched her with songs, played emcee at her events and extolled her supremacy over Mariah Carey.

Now, a laudatory documentary about him, Clive Davis: The Soundtrack of Our Lives, (based on his own memoir) is colliding with a documentary about her that poses difficult questions about race and arrives at the conclusion that there was a psychological cost to being a black superstar whose image was constructed with the express purpose of maximum crossover.

His film opened the Tribeca Film Festival. A great party was given. Jennifer Hudson sauntered through the crowd at Radio City Music Hall, singing a medley of Houston’s greatest hits.

Then came mixed reviews – and the debut at the festival of Whitney: Can I Be Me, a contrasting documentary that casts Houston as a victim of the music business’ most base inclinations.

In it, Kenneth Reynolds, who worked at Arista, the label founded by Davis where Houston made her career, recounts how material that “was too black sounding was sent back”. Kirk Whalum, who played saxophone on several of her tours, describes a woman who became devastated to learn that black people were calling her “White-ney” and a “sellout.”

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

Enjoy unlimited access to 100 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial. Terms apply.

ADVERTISEMENT. If you sign up to this service we will earn commission. This revenue helps to fund journalism across The Independent.

More than a half-dozen colleagues of Houston’s say in the film that the singer’s spiral into addiction had as much to do with her sexuality as they did with race.

Houston’s relationship with Robyn Crawford, an essential person in her camp from 1984 to 1999, was the subject of speculation and gossip. Now, the narrative that the two were lovers had gained real currency, even without confirmation from Crawford.

Reynolds, who toured the country with Houston during the promotion of her debut album, described her lesbianism as “an open secret” at Arista then.

And “Every Little Step,” a recent book by Houston’s ex-husband, Bobby Brown, also posits that Houston’s sexuality was part of her struggle. Her marriage to him, Brown suggests, gave her the ability to reclaim her blackness while holding on to a basic image of straightness. “They couldn’t let Whitney live the life she wanted to live; they insisted that she be perfect, that she be someone she wasn’t,” Brown writes. “That’s why they wanted Robyn out.”

Some people were circumspect about who “they” were. Brown wasn’t. He meant, and named them as, “Clive Davis and her family”.

Love Is a Contact Sport

“An artist can be extremely gifted and yet remain unsuccessful if he or she records the wrong music, or gets an image that confuses potential audiences.” That’s from Davis’s first memoir, from 1974: Clive: Inside the Music Business.

Being out as lesbian or bisexual certainly would have confused audiences in 1985, said actress/comedian Rosie O’Donnell, who knew Houston and Crawford socially and said that she had “no doubt” they were together and that what they had “was real”. (Crawford declined to speak for this article and did not submit to an interview for Whitney: Can I Be Me.)

Back then, O’Donnell said: “There was no Ellen. There was no Will & Grace.”

“Whitney was the first evidence I had that people were willing to acquiesce to whatever it was in order to hold on to an image that wouldn’t offend, because at the time, it meant you wouldn’t have a career in show business,” O’Donnell said. “None.”

The decision to come out was also hard for those in the music business who worked behind the scenes.

David Geffen, the veteran record label owner and manager, publicly disclosed his sexuality in 1992. His friend Sandy Gallin, who managed Dolly Parton and Barbra Streisand, followed in 1994, around the time Rolling Stone co-founder Jann Wenner left his wife for a man.

Yet it wasn’t until 2013 that Davis as well acknowledged what many had known for a while: that after two marriages and four children, he was living with a man. The New York Times reviewer who panned his second memoir wrote: “Though we do hear about his failed first marriage, his second and its aftermath go MIA for several hundred pages before he awkwardly cops to being ‘bisexual’ and in ‘a strong monogamous relationship for the last seven years’ with another man.”

Count on Me

Davis’s life is a story, and he’s a dazzling character in it. It’s his tinted glasses, snazzy suits and apparent fondness for telling tales again and again – life as a rolling press junket. Some of those stories strain credibility, but he probably didn’t wind up as a co-writer of Air Supply’s “All Out of Love” by being principally concerned with the opinions of skeptics.

From 1967 to 1973, he headed Columbia Records, which he helped transform into the biggest label of the rock era. He signed Joplin, Santana and Blood, Sweat & Tears. He pushed into R&B and disco via a promotion and distribution deal with Philadelphia International, home to the O’Jays and Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes.

Then he was fired over expense account violations that included an $18,000 (£13,640) charge to the company for the bar mitzvah of his son. (He maintains he did nothing wrong.)

Determined to rebuild his reputation, Davis started Arista, where he signed Patti Smith, Lou Reed and Dionne Warwick.

His first queen at the label was Melissa Manchester, who came to him as a talented singer-songwriter, hoping to do serious contemplative songs. They had big hits together, but she also learned the cost of having an executive so focused on the marketplace.

“We could not find a comfortable way to communicate,” Manchester said. “He always wanted me to be current, and I always wanted to be timeless. It’s a different way of looking at the same picture.”

Another star from that era, Barry Manilow, left Davis after conflict over his artistic persona – but not before the thorny issue of his homosexuality was handled with a story that he was living with a production assistant, Linda Allen. He came back when his first album without Davis bombed.

“There’s this eternal argument between the part of us that wants to be an artist and the part of us that wants to be a success,” said Carly Simon, an Arista artist. “The success part often wins.”

Same Script, Different Cast

Davis never liked being called a Svengali to Houston. He thought that sounded slithery. But how else to describe their relationship?

Two weeks after Davis signed her, he went on The Merv Griffin Show and introduced his protégé to the world. She hadn’t recorded a song yet, but that was how much he believed in her. Also, he loved going on television.

In 1985, the Whitney Houston album was released and sold 15 million copies in the United States alone. She won a Grammy in the pop category for “Saving All My Love for You” but lost in the R&B category for “You Give Good Love” – a clear indication of the success of the appeal to white audiences.

Simon said: “He is on the side of the winner at all costs, and the cost can be very high. The cost can be somebody’s career or somebody’s innateness.”

In 1987, Houston’s follow-up album arrived, and four singles all hit No 1, making her the first artist in history with seven consecutive chart toppers. “I said, ‘Whitney, are you pinching yourself?’ and she said, ‘Yeah, Clive, I’m pinching myself,'” Davis said.

It’s a story he loves to tell, but the tale was abbreviated.

The reviews for the follow-up album had been brutal. Over and over, she was treated as a Hallmark card with lungs.

Behind the scenes, Houston was increasingly under pressure, by a family that depended upon her and whose appetites seemed to be nearly bottomless.

She made her father her manager and bought her mother a new house. They had divorced after their daughter was famous. She was taught how to freebase cocaine in the late Eighties by her brother Michael. Crawford went to Cissy Houston’s house to say there was a problem.

Cissy Houston had issues with the idea her daughter was gay. She wasn’t open to staging an intervention with Crawford and decided to deal with her daughter’s problem on her own.

Davis seemed equally disinclined to address Houston’s sexuality or what effect hiding that might have had on her happiness or psychological health.

He said he has “no idea” whether she was gay. “We never discussed it,” he said, going on to list the romances she’d supposedly had in the Eighties with Jermaine Jackson and Eddie Murphy.

“Oh, nonsense,” said Fredric Dannen, author of Hit Men: Power Brokers and Fast Money Inside the Music Business. “Clive didn’t know? Of course he knew.”

“For Clive Davis to claim ignorance about this is, I believe, a boldfaced lie,” O’Donnell said.

Davis said that any implication he “orchestrated” a cover-up around Houston’s sexuality or “did not want her to be herself” was “crazy”.

All the Man That I Need

In April 1989, Houston and Crawford attended the Soul Train Awards in Los Angeles. When Houston’s name was announced among the nominees for best R&B/urban contemporary single, female, a loud booing could be heard in the audience.

“I was there,” said producer Kenny Edmonds, known as Babyface. “We talked about it because we were all a little shocked. She was very upset.”

That night, Houston met Bobby Brown for the first time. They flirted, and she invited him to her 26th birthday party in New Jersey. She and Davis also hired Babyface and his partner LA Reid to work on her third album, I’m Your Baby Tonight.

“The irony is that if she was trying to go blacker, I don’t know that we were the guys to go to,” Edmonds said. “We were in the middle. But maybe that’s why Clive called us in the first place.”

Three years later, she and Brown were married. The morning of the wedding, the groom walked into the bedroom of his bride-to-be, he writes in his book, “hoping for a quickie”. When he found her “hunched over a bureau, doing a line of coke,” he couldn’t believe his luck.

“She was classy and street at the same time,” he says in his memoir.

So he bent over and joined in.

By now, Houston was promoting what would become her biggest commercial vehicle yet, The Bodyguard, a demographic-pandering movie she’d just filmed with Kevin Costner.

Even the wedding to Brown became part of the film’s promotion plan, as Houston submitted – with Crawford – to interviews in which they explained that they had not been lovers but were simply best friends. “I think once she’s married she’ll feel a lot more complete,” Crawford said.

Crawford remained part of the management team for seven years, locked with Brown in what several people in Whitney: Can I Be Me describe as a battle for Houston’s affections. During that time, Davis receded somewhat from the picture.

Houston starred in films that grappled more directly with African-American issues but descended further into her own addiction. She suffered an overdose during the making of the 1995 film, Waiting to Exhale. Then she pulled out of big promotional appearances for The Preacher’s Wife because of “throat issues.”

In 1997, Davis’ patience ran out. He wrote her a letter telling her it was time for her to come back to work. Soon enough, Houston was back in the studio, working on My Love Is Your Love, an album that burst with collaborations with edgy producers like Missy Elliott, Lauryn Hill, Wyclef Jean and Rodney Jerkins.

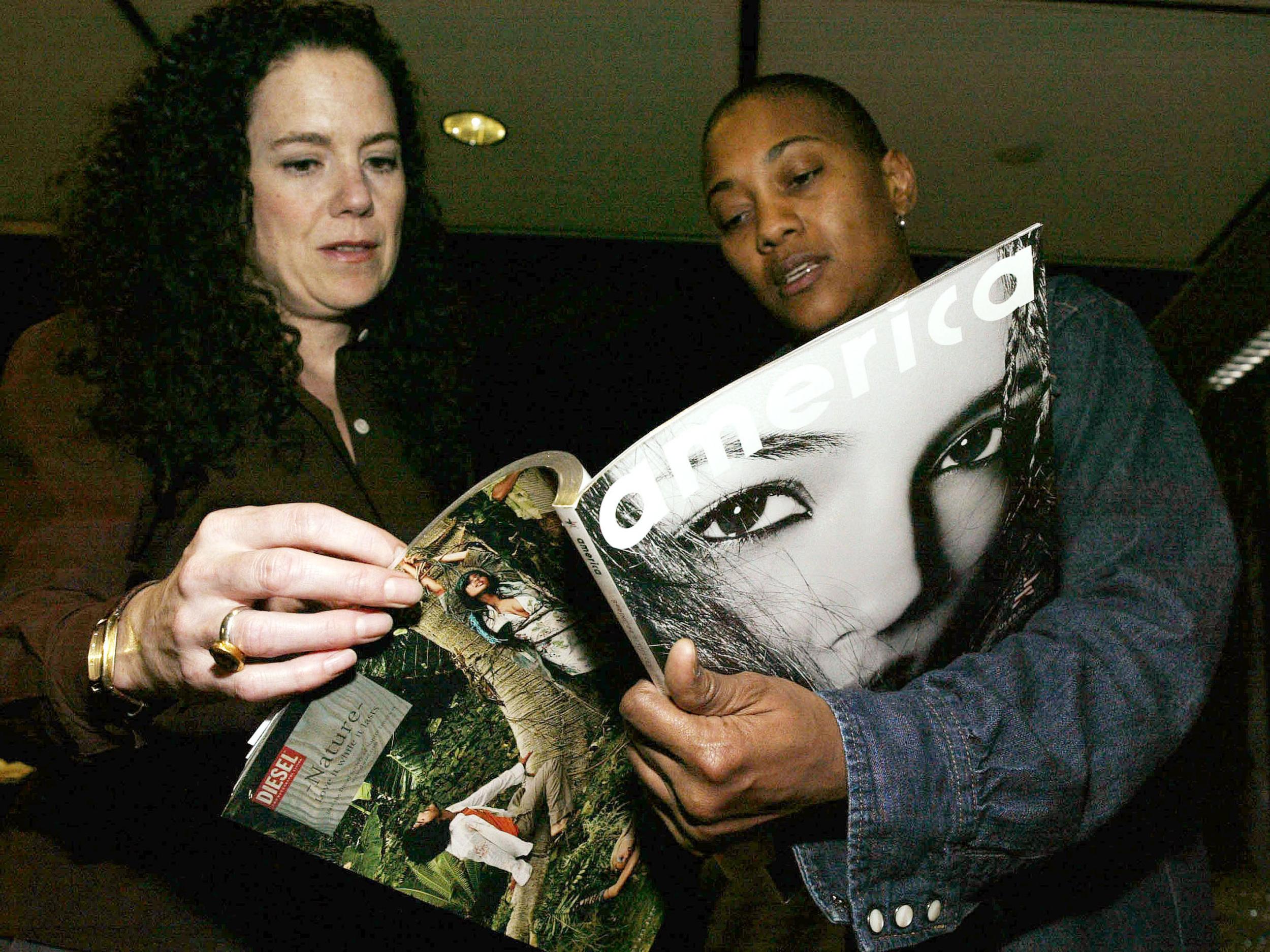

It got some of the best reviews of her career, but the tour was another story. The problem wasn’t the voice, but her marriage’s increasingly Mr and Mrs Smith-like quality. The situation finally broke Crawford, who determined it was time to quit the family business. She also eventually settled down with Lisa Hintelmann, a former magazine editor who works as the director of talent and entertainment partnerships at Audible.

Afterward, said Houston’s former bodyguard, David Roberts, speaking in Whitney: Can I Be Me, Houston seemed to descend further.

How Will I Know

In March 2000, Houston pulled out of a performance for Davis at his induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. A few weeks later she began singing the wrong song during an Oscars rehearsal and couldn’t stay on key. She was fired.

This was around the time Davis said he realised Houston had a drug problem. She told him that she had it under control, that it was her business.

Her 2002 album – made after Davis left Arista to start the new label, J – tanked. She gave a disastrous interview to Diane Sawyer in which Houston explained, in a moment that became notorious, that she did not smoke crack. “Crack is cheap!” she said. “I make too much money to ever smoke crack.”

They did reunite for her last album, and she got divorced. But the combination of cocaine and years of smoking had taken a toll. With her fortune diminishing and her family ever dependent on her, she agreed to stage a tour. It was a disaster.

As far as Davis knew, Houston was sober for the next two years. She seemed to be in good physical shape in February 2012, the week of the Grammys.

They met at his bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel. She said she’d been swimming at least an hour a day and would be ready to go into the studio in August.

Then Houston went out to a nightclub with her daughter, Bobbi Kristina Brown, and left it bleeding. The night she died, the police removed piles of empty liquor bottles and prescription drugs from her hotel room.

Davis did memorialise her at his Grammy event, bringing Alicia Keys and Hudson to the stage to perform songs Houston had made famous.

And he went to Newark, New Jersey, for Houston’s funeral. In his eulogy, he rattled off all the record-breaking statistics of their 27-year collaboration, name-checking five of her 11 No 1 songs, five more Top 10 hits, four of her movies and one very famous rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner”. Yet again, but not for the last time, he told the story about how he’d asked her in 1987 whether she was pinching herself at her success.

Crawford didn’t speak that day. Instead, she posted a remembrance on Esquire’s website.

A lot was left out. But she did give her diagnosis for what happened to Whitney Houston. “The record company, the band members, her family, her friends, me – she fed everybody,” she wrote. “Deep down inside that’s what made her tired.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks