Women in science fiction: If Mary Shelley invented the genre why are so few female sci-fi writers household names?

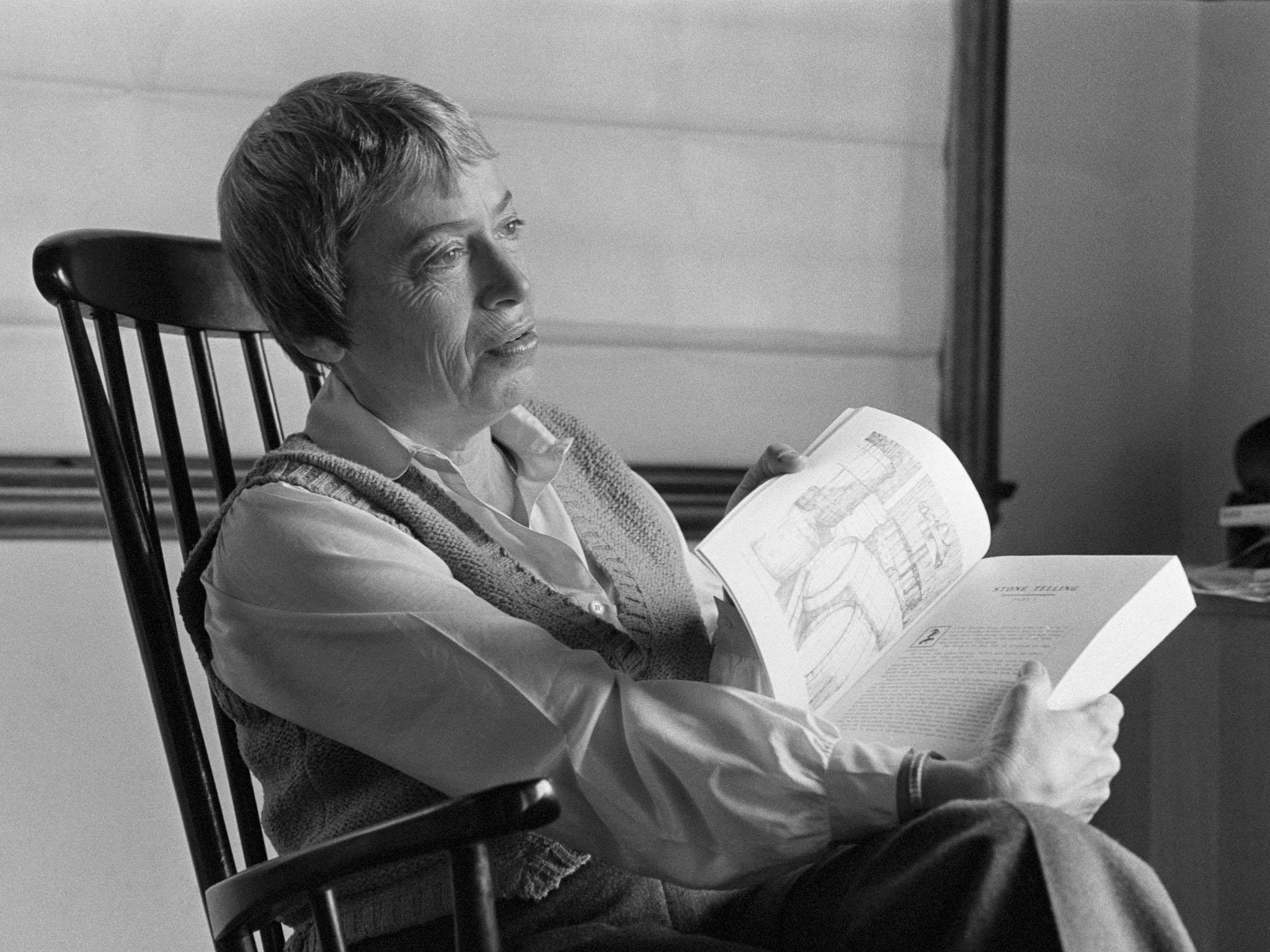

Two hundred years ago, Mary Shelley sat down to write a ghost story and created science fiction. Women still pen the genre’s finest, exemplified by Ursula K Le Guin, who died this week. Yet so often they are overlooked. David Barnett asks: whither the brides of Frankenstein?

Two centuries. Two hundred years. That’s how long we’ve had science fiction. From the birth of Frankenstein, to the death of Ursula K Le Guin. Two hundred years.

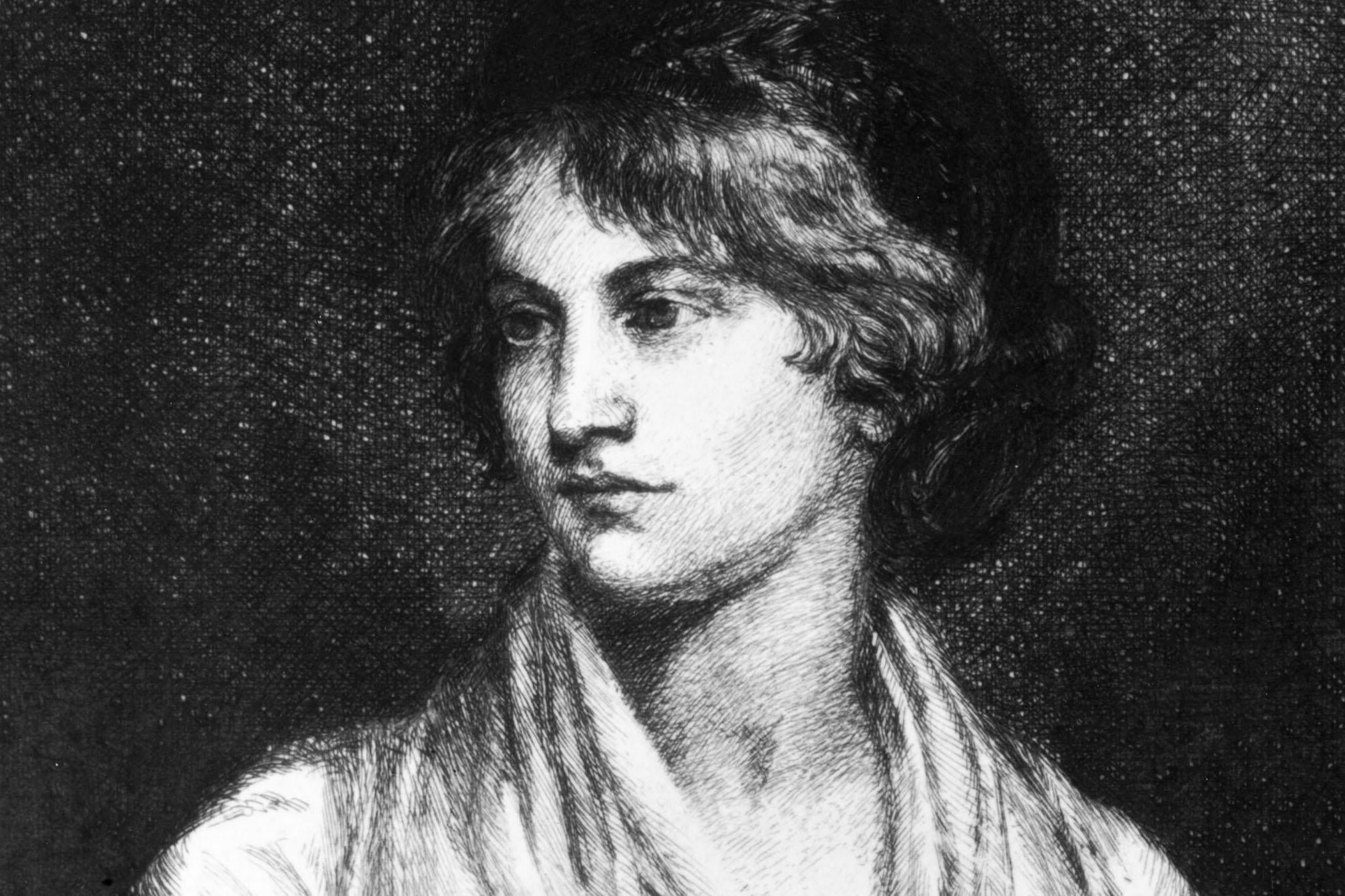

This was originally meant to be just the story of Frankenstein, written by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and published on 1 January 1818. But this week, with the death of one of the greatest science fiction writers of the past century, Ursula K Le Guin, at the age of 88, the lens lurched and shifted and something else was brought into focus: the role of women in science fiction.

The genesis of Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus, to give its full title, is a tale as oft-told as Shelley’s actual story of scientist Victor and his monstrous creation. Aged just 18, the writer was visiting the Villa Diodati near Lake Geneva with her husband, the poet Percy; the property was rented by Lord Byron and John Polidori for the summer of 1816, and the Shelleys were staying close by.

One evening, Byron suggested that they all write their own ghost story. Mary Shelley writes in her introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein: “I busied myself to think of a story – a story to rival those which had excited me to this task. One which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature, and awaken thrilling horror – one to make the reader dread to look around, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beating of the heart.”

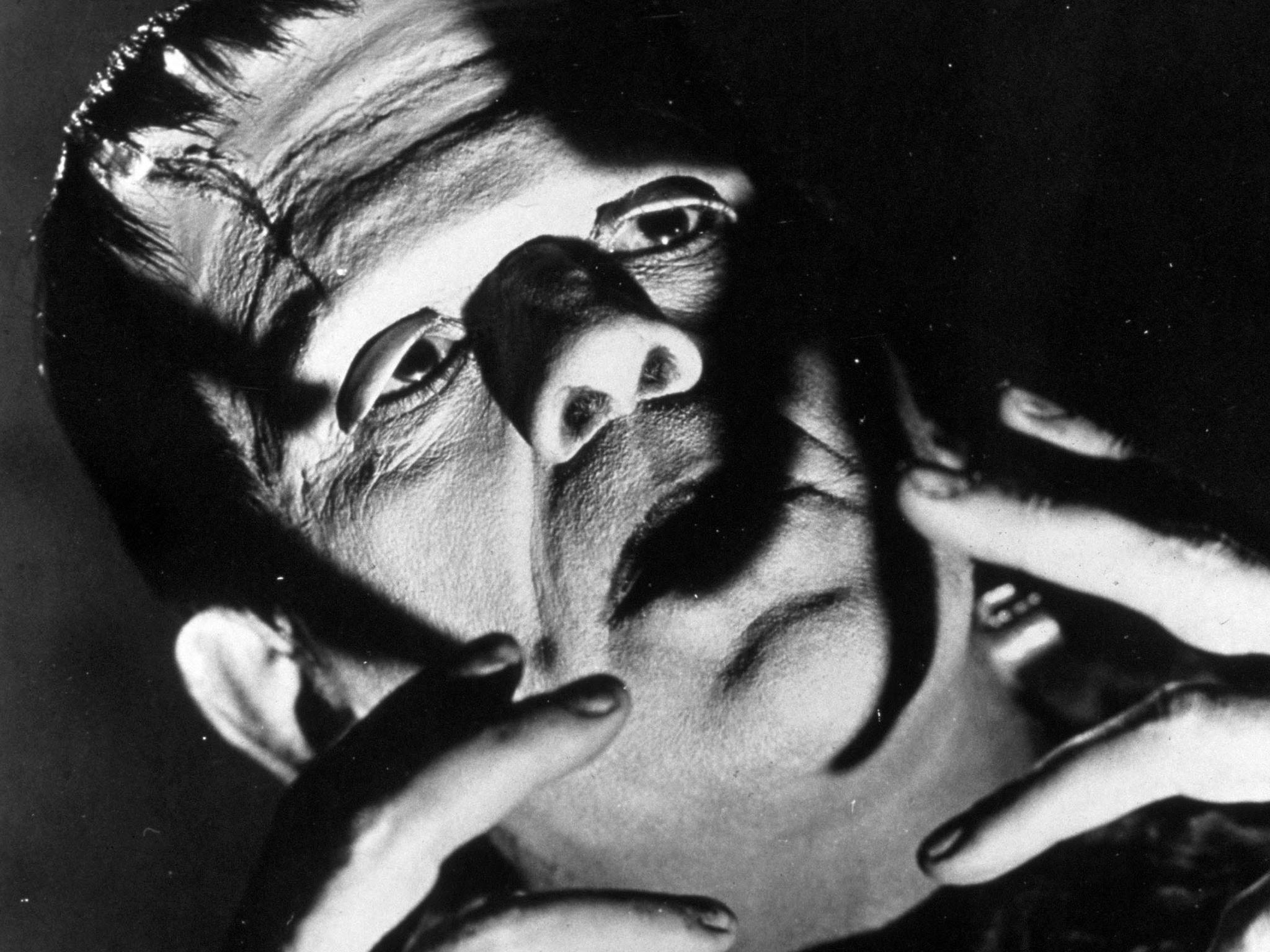

That she certainly did. Frankenstein’s monster has its place in the horror hall of fame. Everyone knows the creature. But do we really know the story? The basics, of course, imprinted on our collective cultural psyche from umpteen movie adaptations. Victor Frankenstein breaks the last taboo by daring to play god and create life, harnessing electricity to reanimate an eight-foot monster made from the stitched-together parts of stolen corpses, which then goes on a terrible rampage.

Though in the horror fraternity of Dracula, the Wolf Man and the Mummy, Frankenstein’s monster is completely science fiction, created by science, not the supernatural. And Mary Shelley’s novel is far more nuanced than the cartoonish image we have of the bolt-necked, green-tinged monster lumbering around in pursuit of screaming women.

After abandoning his creation in disgust, guilt drives Frankenstein to track down the monster in the Alps, where the creature reveals it has spent their time apart becoming quite erudite, educating itself from a cache of books and developing acute emotional and social sensibilities by observing, at a distance, a poverty-struck family. But with this growing self-awareness comes the knowledge of the creature’s place in the world, and of what he has and has not… and wants.

Directing Frankenstein to create a woman to share the unique space the monster occupies, the creation finally does embrace his darker side when Frankenstein refuses and the monster kills his creator’s wife on their wedding night.

A powerful story, and one that has endured. But there’s a curious thing. Mary Shelley’s detailed explanation of how the novel came about, quoted briefly above, does not appear in the first edition. There is a different introduction in that novel, which states: “Two other friends (a tale from the pen of one of whom would be far more acceptable to the public than any thing I can ever hope to produce) and myself agreed to write each a story, founded on some supernatural occurrence.

The weather, however, suddenly became serene; and my two friends left me on a journey among the Alps, and lost in the magnificent scenes which they present, all memory of their ghostly visions. The following tale is the only one which has been completed.”

It’s curious because it’s very self-deprecating. Mary Shelley is essentially saying that the boys got distracted from the job of writing ghost stories because they went to have some laddish fun outside, though if they had finished the task then their work would easily have been better than anything she could write, and she’s almost apologetic in her presentation of it, because it’s the only one that there is to offer from that night at Villa Diodati.

Which we now know to be wrong, because a fraction of Byron’s story did appear at the end of his poem “Mazeppa”, and Polidori’s The Vampyre was later published in 1819. The introduction is all the more astonishing, though, because Mary Shelley didn’t write it. Her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, did, subtly shading her achievements by setting them against far superior work he and his mate would have done if only they could have been bothered.

Fast forward to 1983, and the author Joanna Russ publishes a book called How To Suppress Women’s Writing. The cover of that book has become famous not for any image or visual but for what has become a mantra which explains the thrust of Russ’s argument: “She didn’t write it. She wrote it but she shouldn’t have. She wrote it, but look what she wrote about. She wrote it, but she only wrote one of it. She wrote it, but she isn’t really an artist and it isn’t really art. She wrote it, but she had help. She wrote it, but she’s an anomaly. She wrote it BUT…”

Excuses. Reasons. Explanations. Mansplanations. Women’s writing generally has been marginalised and subdued since book publishing began, but it’s often through a whispering campaign rather than actually taking typewriters away from women or banning them from writing. Sowing the seeds of doubt. Justification, saying well, okay, this book is not bad, but I bet she couldn’t do it again. Or some man must have helped her. Or, fine, she’s a good writer, but she’s a one-off. Most women don’t write like that.

It’s no coincidence that the author of this book, Joanna Russ, was also a science fiction author up to her death in 2011. Russ began to get published in the 1960s with the short story collection Picnic on Paradise in 1968, the same year that Ursula K Le Guin published A Wizard of Earthsea. Russ’s most often-cited book is The Female Man, from 1975, which features four women in different parallel universes who visit each other’s realities and compare and contrast the lives and treatment of women.

Russ and Le Guin were writing in a period of great science fiction, those post-Second World War years with their technological advances and exploration of space melting into Cold War and the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation. But ask most people who are the major science fiction writers of the second half of the 20th century and I’ll bet you’ll assemble a list of mostly male names.

If you don’t believe me, take a look at ranker.com, a website that allows users to rank pretty much anything. Go to the list of “Greatest Science Fiction Authors”. Isaac Asimov. Philip K Dick. Arthur C Clarke. HG Wells. Robert A Heinlein. Frank Herbert. Ray Bradbury. Giants all, no disputing that. The first woman’s name appears at number 10 on the list, Ursula Le Guin. We don’t see another one until 29 – our friend Mary Shelley, followed at 30 by the author of the Pern series, Anne McCaffrey. There are 13 women in the top 100 in all, most of them appearing in the lower reaches, as ranked by the 70,000 users who have engaged with this particular topic.

Why aren’t there more? Maybe because science fiction, particularly in the golden age years, was just seen as something men did. Maybe because the boys’ club atmosphere put women off. Maybe women weren’t welcome. The first edition of Frankenstein was published anonymously. In 1967, a new science fiction author came on to the scene, James Tiptree Jr. It was at least a decade before the author of dozens of thoughtful, intelligent and often subversive short stories was revealed to be a woman called Alice Sheldon. In an interview with Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine in 1983 she said of her pseudonymous career: “A male name seemed like good camouflage. I had the feeling that a man would slip by less observed. I’ve had too many experiences in my life of being the first woman in some damned occupation.”

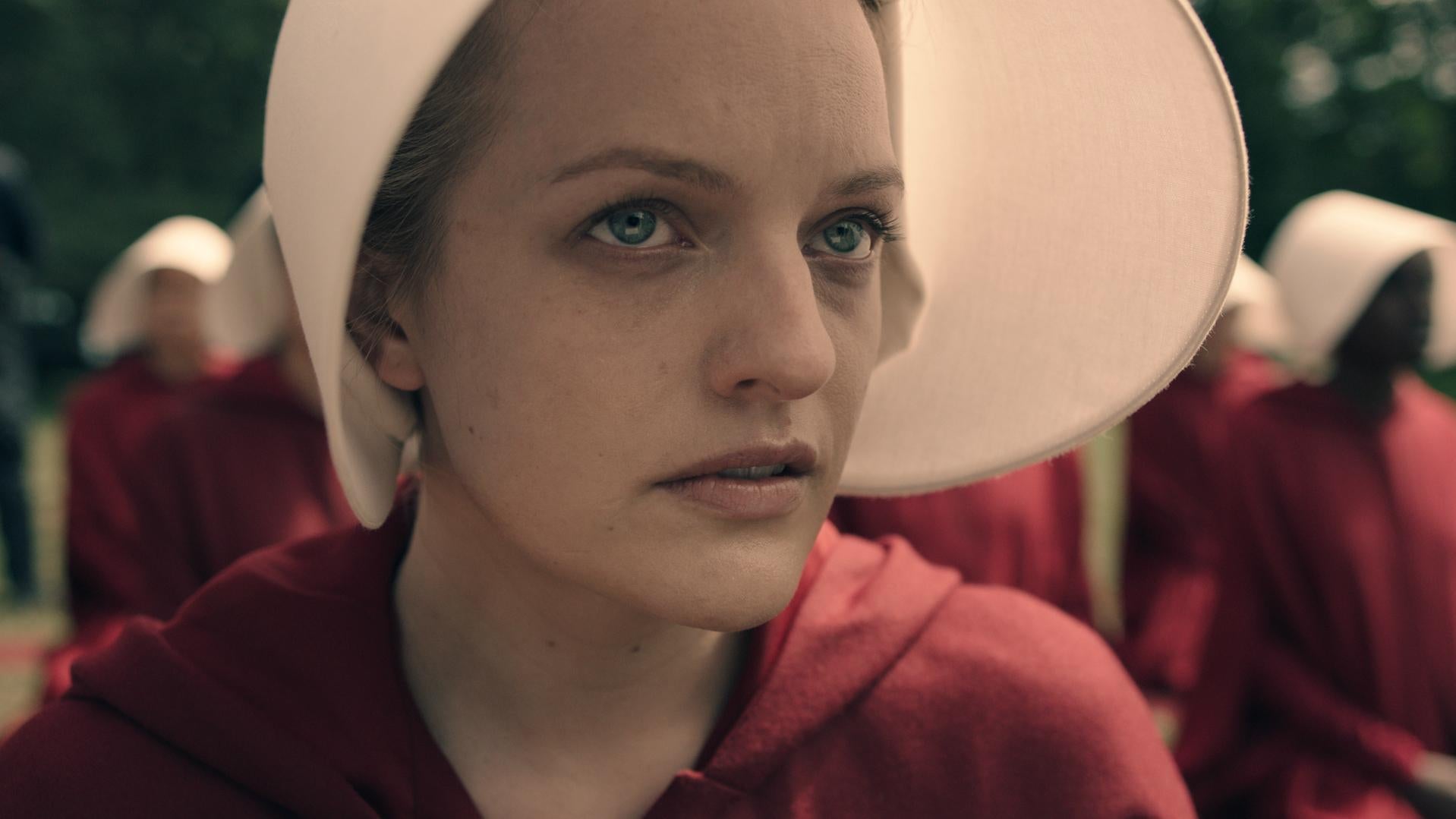

Women write science fiction. Women have always written science fiction. But often, they have been ignored, or sidelined, or simply slid under the radar. If they’re very good at writing science fiction, they can get co-opted out of the genre and into “literary fiction”. Take, for example, Margaret Atwood, whose work is out and-out science fiction, from The Handmaid’s Tale to Oryx and Crake. Atwood once infamously said her work wasn’t science fiction at all, because that was all about “talking squids in outer space”.

It was perhaps when Atwood relented on that and embraced her science fiction genes that things began to change. More notice was taken of those who had gone before, and successive new generations of genre writers had their ranks noticeably swollen by women. There’s an excellent website run by Ian Sales (a man, but we won’t hold that against him) at SFMistressworks.wordpress.com that is dedicated to reviewing books by women writers, both new ones and lost gems from the past. The name might sound a bit clunky but it’s a direct response to the series of yellow-liveried books that reprints classic SF novels under the banner SF Masterworks. It’s a good place to start if you want to build a reading list of woman-penned science fiction.

But why should you anyway? Well, because science fiction written by women seems, on the whole, to be vastly superior to that written by men. Why? Good question. I asked Twitter this week. It didn’t disappoint.

“Because we’re always navigating an alien territory, where the Other is the default, but where we have learned to walk in his shoes” – @evilrooster

“Because women are more often required to consider experiences outside their own and exhibit empathy? (If we are talking in generalisations). Or perhaps women want to create something really different while many men want the status quo but with spaceships?” – @FoxSpiritBooks

“Maybe because more women authors than men write character driven books that address complex issues? Is it my imagination, or are far too many men’s SF books post apocalyptic “shoot ‘em ups”?” – @Bookworm369

“One reason might be because they’ve always had to try harder, imagine wider, write better to even get published. Male writers have had it easy and don’t push themselves nearly as hard as they could.” – @neilwilliamson

“Because the world is good to men, and women have always had to (re)imagine a world that is better to them.” – @piabesmonte

If you look at the science fiction shelves of your local bookshop today, you’d be forgiven for thinking it’s always been an equitable game in terms of gender split. Writers such as Kameron Hurley, NK Jemisin, Mur Lafferty, GX Todd, Ann Leckie, Naomi Alderman, Nina Allen, Nnedi Okorafor… so many names, writing so many new and exciting and diverse and different books, that one hesitates even to try to make a list because it will only scratch the surface.

But it hasn’t always been this way, it’s been a fight. Sometimes it’s been a fight on the front lines by the likes of Joanna Russ, sometimes it’s been a battle of subterfuge, by the likes of Alice Sheldon. Sometimes it’s been an intersectional fight on many fronts, by the likes of Octavia Butler.

But it’s always been a fight, and one that continues.

It was a fight for Mary Shelley, too, of course, the woman who created the genre and whose book was published without her name on it with an introduction written for her by her husband.

But remember this: Mary Shelley was originally tasked to write a ghost story. Instead she invented science fiction with a novel that spoke of horrors yet pierced the heart of humanity. Women, eh? Never doing what they’re told, breaking all the rules, and creating things of a rare and lasting power.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks