World Book Day 2018: Eight underrated novels by great writers that deserve a wider audience

Even literature's canonical authors can see their work unjustly gathering dust on the shelf

World Book Day seems like an ideal opportunity to reassess the great writers in the literary canon and shine a light on some of their lesser-known works.

Tomes like FR Leavis’s The Great Tradition (1948) have long-since established the pantheon of our finest authors, sanctifying literature’s leading lights from Jane Austen to Joseph Conrad.

But such undertakings are inevitably subjective and prone to being distorted by personal prejudice – as indeed is the list to follow. Leavis’s decision to exclude the likes of Laurence Sterne, Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy, for instance, was as unfathomable at the time as it appears today.

Even for those writers who are firmly established as canonical and never fall out of fashion, the popularity of certain key works - often those routinely adapted for film, television and radio - can come to overshadow the rest of their output.

A brilliant novelist like Laurie Lee was prolific in his day but the success of Cider With Rosie (1959) has proven the kiss of death for sales of much of the rest of his work.

In an attempt to redress the balance, here are eight examples of books by revered authors that deserve a wider audience.

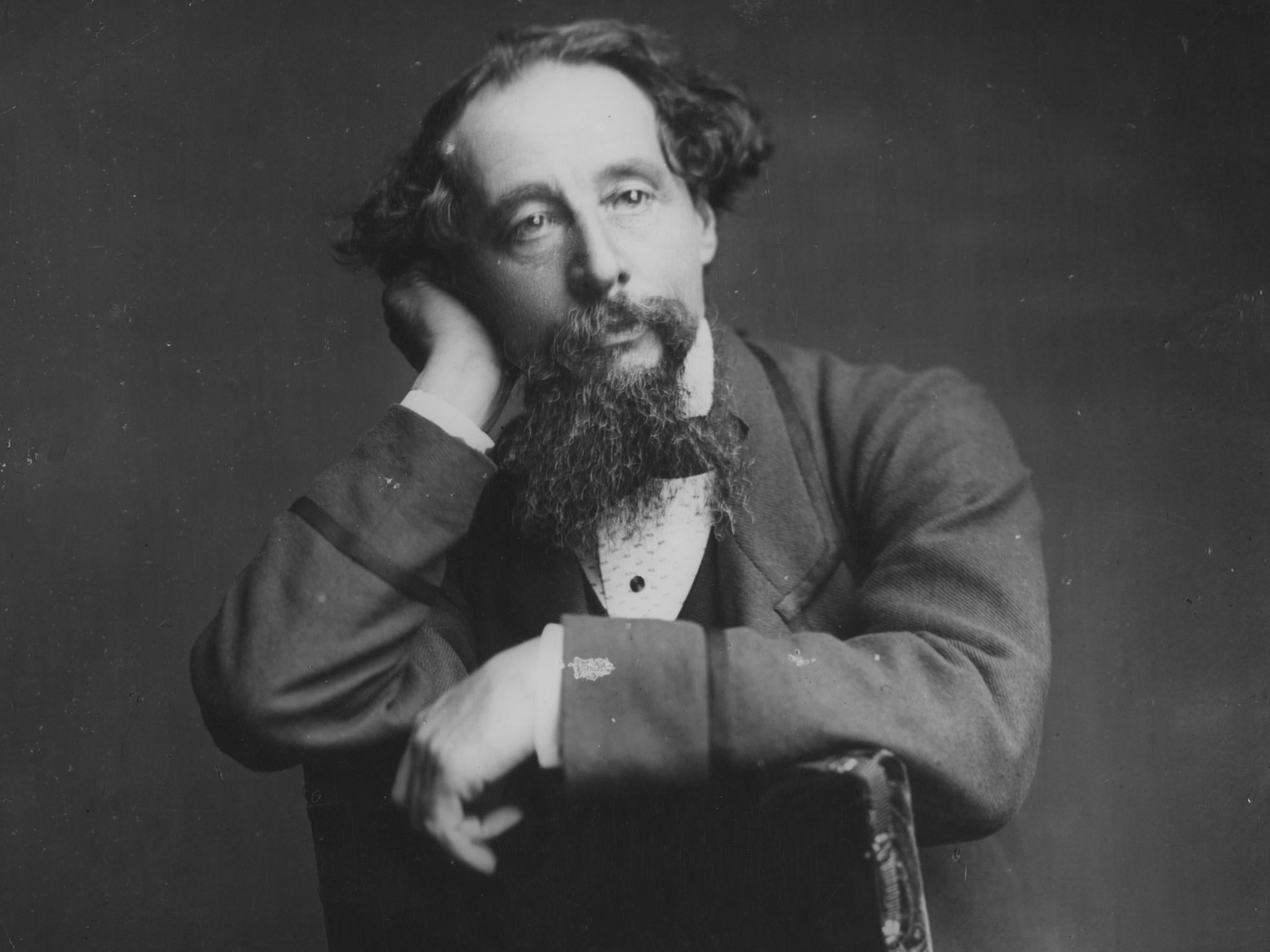

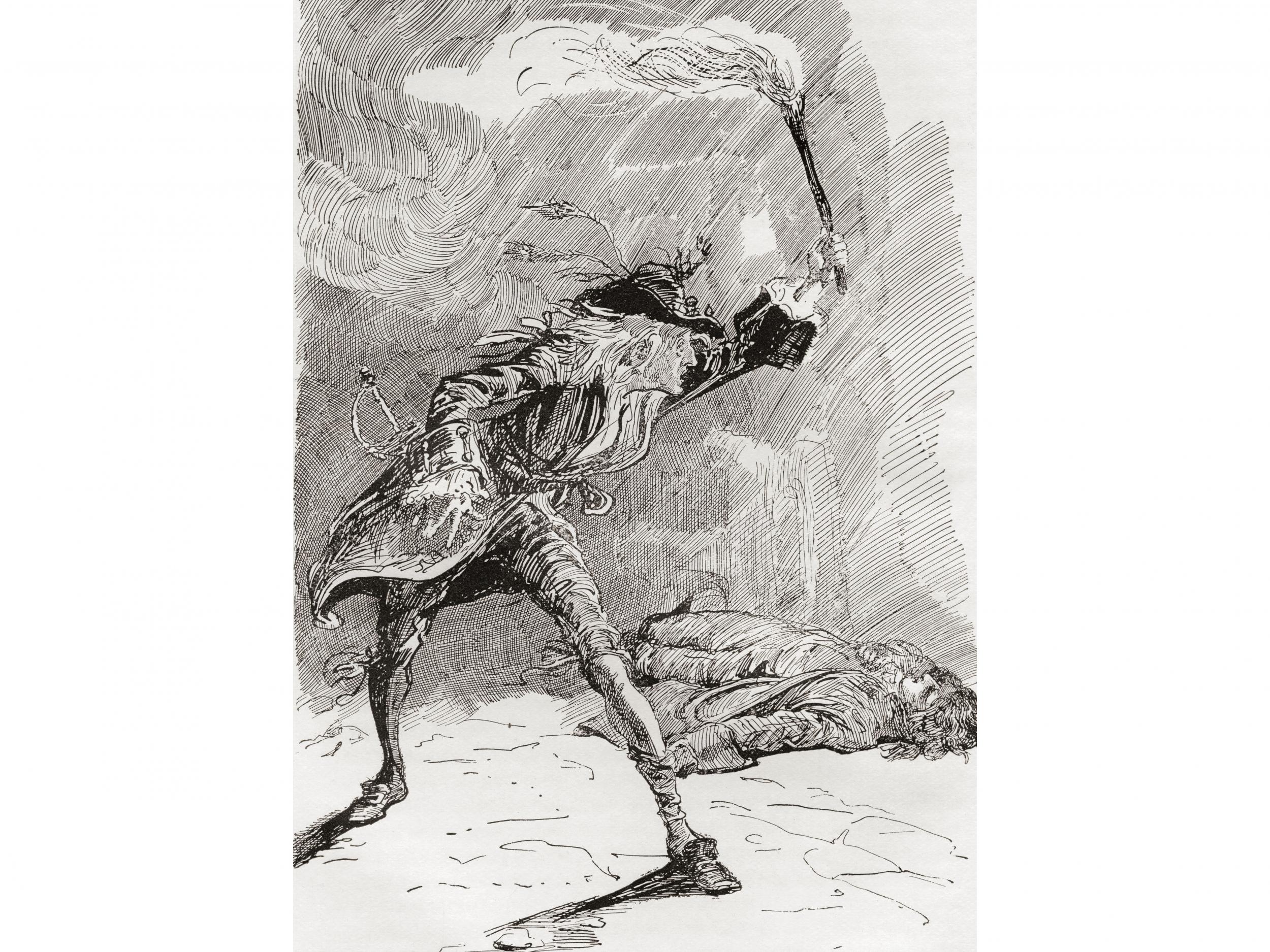

Barnaby Rudge (1841) by Charles Dickens

Everybody knows Dickens’s seminal novels and his many classic characters, comic and gothic. But while few venture beyond Oliver Twist (1839), A Christmas Carol (1843), David Copperfield (1850) or Great Expectations (1861), all of his writings contain something worth savouring: be it a slice of uproarious satire, a heart-breaking demise or a biting piece of social comment.

Barnaby Rudge boasts the latter in spades. A historical novel serialised in 1841 but dealing with the Gordon Riots of 1780, Dickens uses the "no-popery" uprising inspired by Lord George Gordon’s inflammatory rhetoric against the Roman Catholic "infiltration" of Britain in the 18th century as a means of attacking mob mentality and the hijacking of political causes for crude personal gain. Recommended reading in Brexit Britain, trust me.

Typee (1842) by Herman Melville

In Moby-Dick (1851), American novelist Herman Melville wrote a serious contender for the greatest novel of all time, a colossal artistic achievement. In 'Bartleby the Scrivener' (1853), he created one of the most devastating short stories ever conceived.

Both works are astounding examinations of the human condition. But neither saved him for being overlooked in his own lifetime and dying in obscurity in 1891, his name famously misspelled in a New York Times obituary.

Perhaps less well known today is Typee, his first novel, “a romance of the South Seas” inspired by his experiences as a young sailor in the Pacific. A brilliant piece of a travel writing, faithfully recording the lush landscapes of the Marquesas Islands, it is also a thrilling colonial adventure story concerning two American mariners cast adrift among rival cannibal tribes, struggling to decipher which side is friendly and which malevolent. Authentic, deeply atmospheric and chilling.

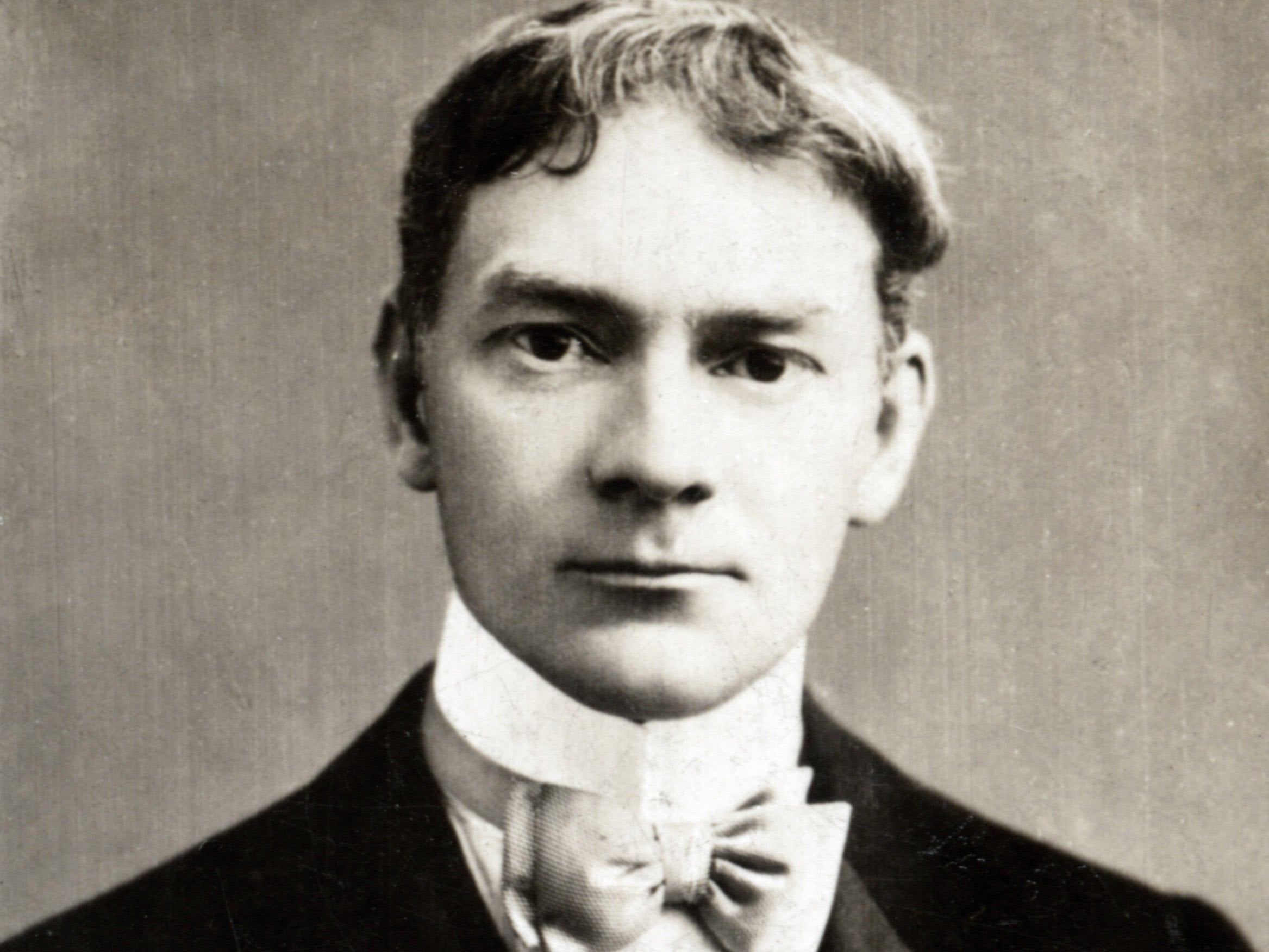

Three Men on the Bummel (1900) by Jerome K Jerome

Three Men in a Boat (1889) remains a beloved British classic, the tale of the author and his friends Wingrave and Harris – plus their dog Montmorency – getting into scrapes, stepping in the mustard and toppling into the Thames on a supposedly relaxing jaunt up river from Kingston to Oxford.

While that novel has never been out of print and one seldom passes a second-hand book shop without spotting a copy, its sequel is much overlooked. The three heroes of the original reunite in extended middle-age to go on a cycling holiday to Germany’s Black Forest.

Equally as filled with comic incident and humorous mishaps as its precursor, Bummel (its title employing a German word for “journey”) finds fresh meat in sending up Teutonic customs from a late Victorian, very British point-of-view.

Jerome characterises the German people he encounters as being in thrall to authority, an uncomfortably prescient observation given what was to follow in the century then dawning and the sort of detail that ensures the book has more lasting interest than it might otherwise have offered.

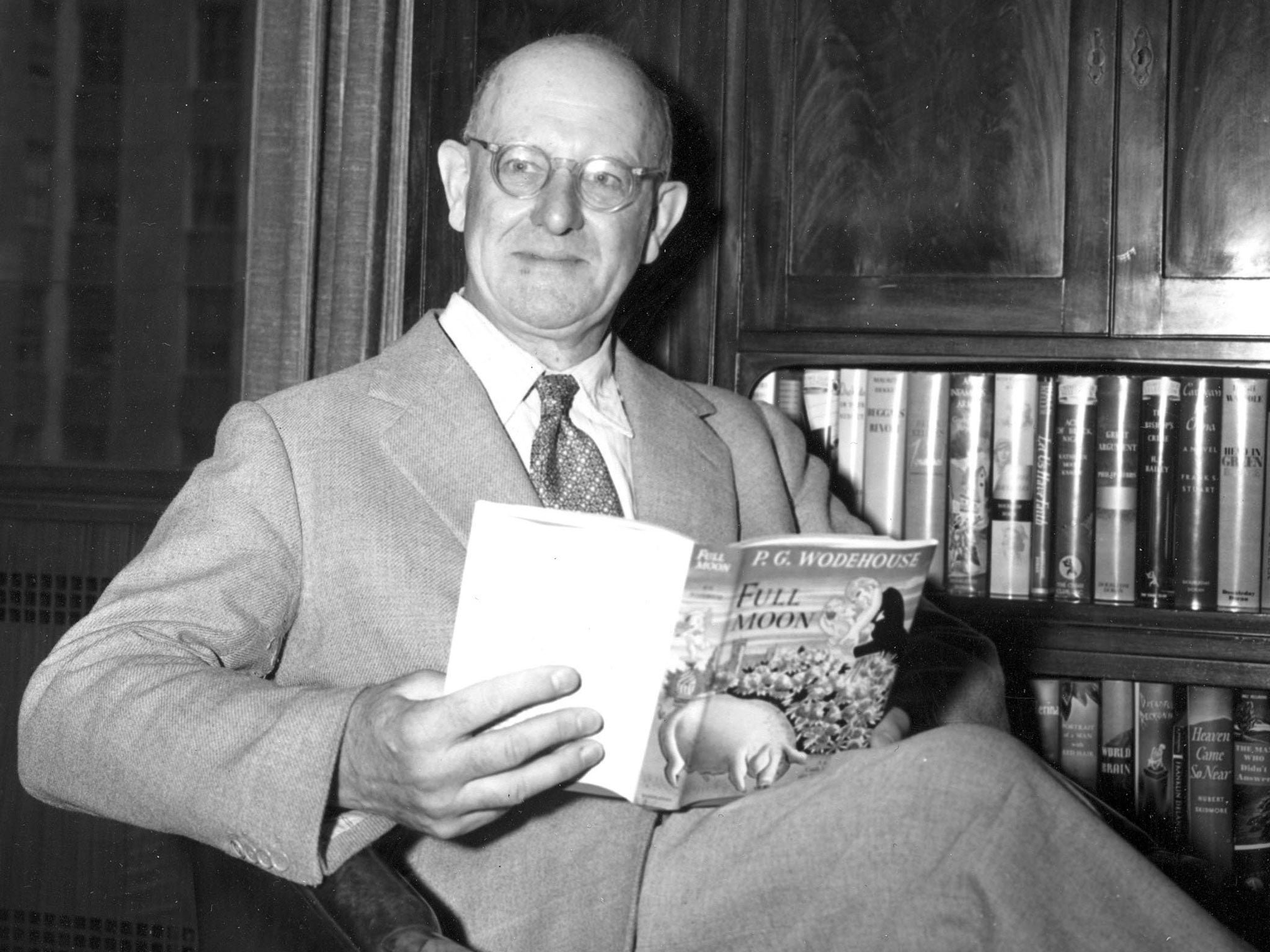

Leave It to Psmith (1924) by PG Wodehouse

Jeeves and Wooster are rightly adored as English literature’s favourite double act. Their tales of dreary fiancées, lovestruck newt-fanciers, violent aunts and high society farce have been the nation’s preferred comfort reading for over a century.

Wodehouse created a number of other brilliant comic characters, however. Psmith (the “P” is silent but insisted upon) is one such, a breezy gadfly who caused chaos across four extremely satisfying novellas between 1909 and 1924.

Following Psmith's introduction in Mike, his adventures as a broker in Psmith in the City (1910) and tackling the Fourth Estate in Psmith, Journalist (1915), Wodehouse revived him once more for Leave It to Psmith, which finds the master comic writer at the height of his powers, pitting Psmith against Lord Emsworth and family at Blandings Castle in a daring crossover plot. Forget Marvel, this is the cinematic universe we ought to be demanding.

The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles (1958) by Giorgio Bassani

Italian writer and editor Bassani is perhaps best remembered for discovering someone else’s masterpiece: Guiseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1958), unquestionably one of the greatest of all European novels.

Bassani was editorial director of Milan’s Feltrinelli publishing house when he received the aristocrat’s manuscript and was among the first to recognise the brilliance of Lampedusa’s dissection of Sicilian grandeur in decline.

Bassani was an admired writer in his own right and known for his series of short stories and novellas about his native Ferrara’s Jewish community and their trials at the hands of Benito Mussolini’s brutal Fascists. That same year, he produced The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles, an elegantly written portrait of a shy doctor struggling to conceal his homosexual inclinations in intolerant times.

Overshadowed by The Leopard and Bassani’s own classic The Gardens of the Finzi-Continis (1962), this earlier work owes a debt to Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912), anticipates Andre Aciman's Call Me By Your Name (2007) and deserves new readers.

This Sweet Sickness (1960) by Patricia Highsmith

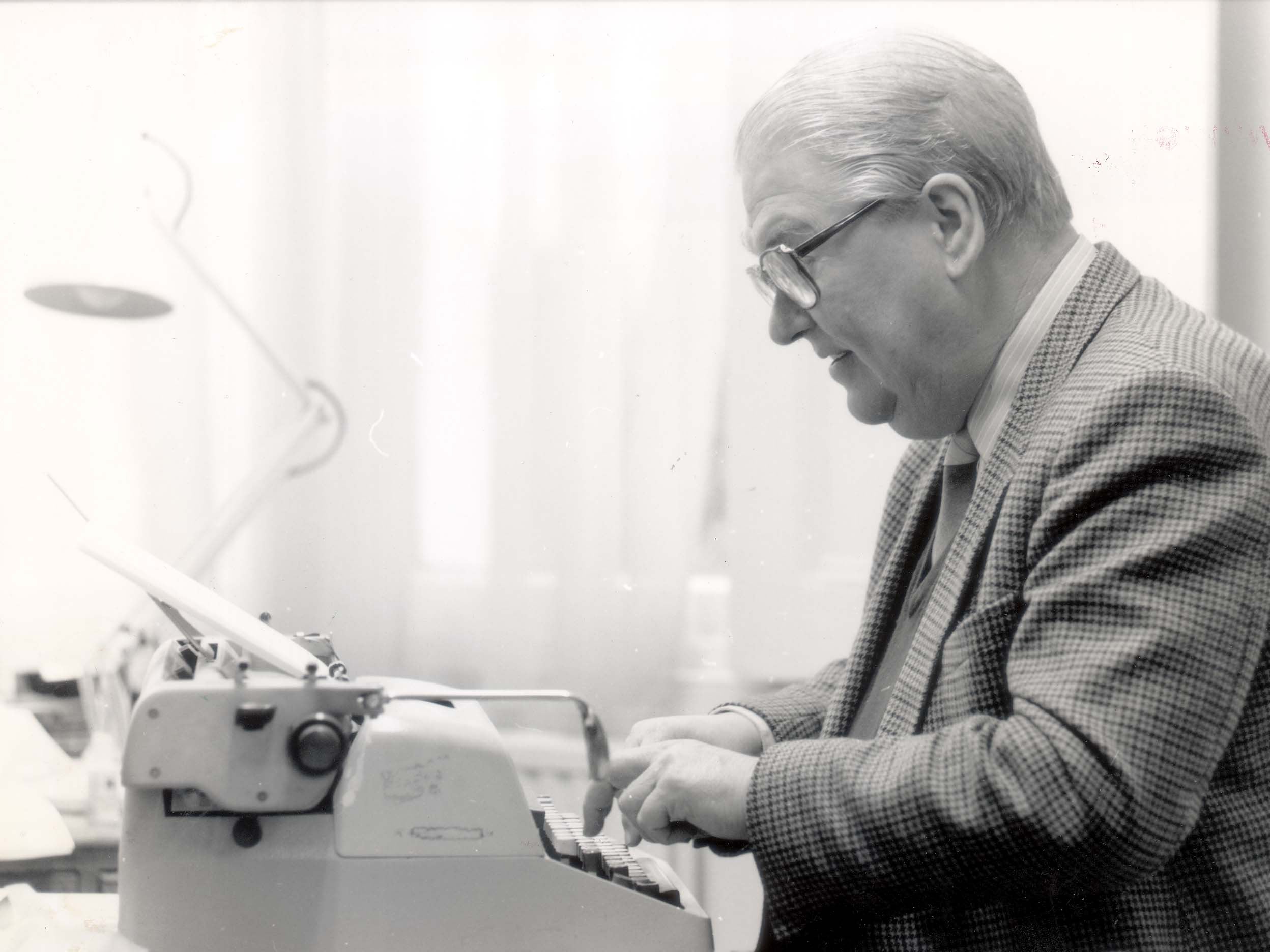

Highsmith is one of the finest practitioners of the psychological thriller to ever set up shop behind a typewriter, her Tom Ripley novels greatly admired and frequently adapted. More recently, she drew new legions of fans thanks to the success of Carol, Todd Haynes’s brilliant film translation of her pseudonymously-penned lesbian romance The Price of Salt (1952).

This Sweet Sickness is a terrifying portrait of a psychopath infatuated with a woman who has rejected him. Building on the envious outsider of The Talented Mr Ripley (1955) and anticipating the “peeping Tom” themes of Cry of the Owl (1962), Highsmith’s tormented stalker David Kelsey is a tragic monster, a fearless portrait of obsession that leaves one questioning the author’s own wellbeing.

Clock Without Hands (1961) by Carson McCullers

American novelist Carson McCullers only completed four novels in a short life curtailed by illness and alcoholism. Associated with the Southern Gothic style, her astonishing debut The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940) remains her most enduring success. However, her final novel also deserves another look.

Recommended for anyone who enjoyed the sweltering tensions of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Clock Without Hands tells the story of an elderly judge in rural Georgia reflecting on his career and dreaming of a revival of the Confederacy as the state begins implementing the court-ordered racial integration of its schools. Judge Clane’s inability to accept changing times is contrasted with his grandson’s friendship with a young black orphan, victimised by the townsfolk.

McCullers final statement on prejudice and conflict in the American South wasn’t to everyone’s taste, however, with Flannery O’Connor dismissing it as, "the worst book I have ever read". Make up your own mind.

The Old Devils (1986) by Kingsley Amis

For an extremely busy novelist, few these days read Amis’s work other than Lucky Jim (1954). He appears to have fallen badly out of fashion and is unfairly better remembered as friend to Philip Larkin and father of Martin. This is no doubt in part down to the fact that his very male preoccupations with forgotten jazz LPs, tippling, academic slights and fading potency are insufficiently Instagram-friendly subjects.

This is a pity as Amis was a highly skilled comic writer with much to offer. The Old Devils was one of his last novels – winning the Booker – and is packed with deliciously cantankerous humour, quite unlike anything else out there. It is the story of Alun Weaver, a broadcaster of minor celebrity, who returns home to Wales for a weekend of pub boozing with old friends. The group’s long-brewing resentments and historic infidelities are gradually teased out as the collective become increasingly sloshed and incoherent. It’s lively, vinegary stuff.

So what have we missed? Why didn’t I go to bat for Persuasion (1818) and end the tyranny of Pride and Prejudice (1813), I hear you cry. What a wasted opportunity to stand up for Graham Greene’s Stamboul Train (1932) against the edifice that is Brighton Rock (1938), you howl in torment. Why no mention of underappreciated efforts by Conrad, L.P. Hartley, Joseph Heller or William Golding?

Well, picking favourites is always a losing game. Just ask Leavis. Which neglected works by the undisputed greats do you love?

For more on World Book Day, you may also enjoy our profile of Welsh horror writer and mystic Arthur Machen, another unsung talent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments