Remembrance of Times past

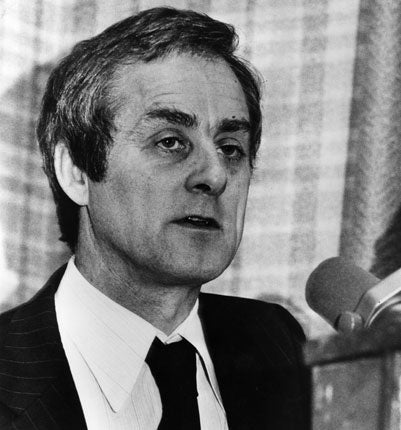

At The Sunday Times Sir Harold Evans presided over a golden age of investigative reporting. Now, as he embraces new technology, how does he see the future of the press?

When Sir Harold Evans arrives he is wearing white running shoes. His wife, Tina Brown, the celebrated magazine editor, is asleep in their room in a fashionable London hotel, following the couple's transatlantic flight the same day, but Sir Harold, 81, fancied a spot of exercise and hit the streets.

He may never have had quite the circulation figures of, say, the Daily Mail's all-powerful Paul Dacre, The Sun's Kelvin MacKenzie or John Junor, who ran the then-mighty Sunday Express for more than three decades – but Harold Evans remains the most-esteemed British newspaper editor of the past 50 years. He is revered mostly for the investigative record of his Sunday Times, whose exposé of the drug Thalidomide and the unmasking of Kim Philby as a Soviet spy transformed the quality press and elevated the status of journalism in the minds of the public.

Although a product of the pre-digital era – "the aromatic urgency of hot metal marinated with printer's ink" as he puts it in his new memoir My Paper Chase – Sir Harold is someone who instinctively embraces change. Asked, for example, about the potential of the Kindle, Amazon's electronic book platform, he says he has one upstairs in his hotel room.

"I'm reading Proust at the moment on a Kindle. It's pretty good actually. I thought, 'Harry, you've gone through your life without reading Proust, what kind of guy are you?' So I summoned up Remembrance Of Things Past, it popped up – the type was too small so I increased its size."

Though he praises Proust's work for its journalistic qualities – "the quality of reporting and observation is amazing" – he confesses that, on returning home from travelling, he took down an unopened copy that had sat on his bookshelf and finished reading the story in its traditional format. "Out of sentimentality I prefer to hold a book and to hold a newspaper," he says. "It's a physical thing."

But he has already discovered technology that can help in providing that crucial tactile comfort. A fortnight earlier, he was holidaying on a boat moored off a remote Greek island. Yet each morning, over breakfast at 8am, he was able to peruse the printed pages of that day's Financial Times, Wall Street Journal and New York Times. "How?" he asks, before answering his own question.

"A Hewlett Packard machine – the HN550. It's fantastic; digital quality printing and the type is very legible."

Since returning home to New York, where he has lived for 25 years, Sir Harold has researched the wider potential of the device.

"This Hewlett Packard machine is available at retail for $2,900, say £1,500, but these prices will come down just as technology has become cheaper. It will become cheap enough for pretty well-off people to put a printer in their house, not just for the newspaper but for other digital printing, photographs and so on.

"Newspapers could encourage this by giving subsidies of some form, or the corner shop can have one."

Such consumption of the press would reduce the costs of printing surplus copies, he points out. "In magazines, the return rate is about 60 per cent. You are printing a lot of waste. Print on demand is coming at lightning speed for books and print on demand for magazines and newspapers is the way to do it."

He is "very, very optimistic" about the long-term prospects for journalism, thanks to the potential of online applications, especially video, and the "unparalleled access to information on a scale never known before". But of course he accepts that news-based businesses have a problem in transiting to this new world.

"I'm rather worried in the short term because the tendency is to produce the cheaper forms of journalism. It won't work in the long term," he says. "The reason The Sunday Times succeeded was not because of me but because [former chief executive of Times Newspapers[ Denis Hamilton and [former Times and Sunday Times owner[ Roy Thomson decided to invest for the long term. When Rupert Murdoch bought The Sunday Times it was a very profitable paper and he made it even more profitable."

Now, as then, it is imperative to find ways of generating additional revenue to fund the "not cheap" process of sending reporters on assignment. "On The Sunday Times we had a number of ancillary activities. After the first exposé on Philby in 1967, the phone rang and it was the publishers saying 'Would you write a book?' It was a huge best-seller and all the costs of investigating Philby were completely written off, in fact we made a profit."

When the Special Air Service rescued hostages from the Iranian embassy in London in 1980, The Sunday Times had a paperback on sale within a week. Other books expanded on the newspaper's reporting of the crash of a DC10 airliner in Paris in 1974, and the Jeremy Thorpe scandal in 1976. Little wonder that Evans would later in his career become president of the publisher Random House.

News International's senior executive Katie Vanneck recently boasted in these pages of the value of The Sunday Times Wine Club which, with 80 million sales a year, has become "one of the largest direct wine businesses in Europe" and, more significantly, offers a database of 300,000 customers, which is central to the commercial future of the newspaper itself. The club was set up under Sir Harold's editorship 30 years ago. "The ancillary activities at The Sunday Times were making a profit of £1m a year," he recalls, stressing the need to plough money back into editorial operations.

Sir Harold's appreciation of the value of reporting is born of his own newspaper apprenticeship – detailed in My Paper Chase – during which he cycled 14 miles to work on the Ashton-under-Lyne Reporter, on the outskirts of Manchester, before going "parring" – knocking on doors at undertakers, working men's clubs and rectories in search of nuggets of news that would make a paragraph of copy. He later honed his craft on the sub-editing desk of the Manchester Evening News and distinguished himself as a campaigning young editor of the Northern Echo, based in Darlington.

Unsurprisingly, he is alarmed by the vogue among cost-cutting newspaper owners for doing away with the role of sub-editor altogether. No writers are infallible, he says. "Where do these superhuman people live? Everybody makes mistakes, I made mistakes in writing this [book], the editors found them. Although I think the reporter is the heart of the paper, subs are crucial to economy of space, clarity of expression and legal safety."

A former editorial director of prestigious American publications including US News & World Report, The Atlantic Monthly and the New York Daily News, Sir Harold is critical of the way some American proprietors have cut back on content and devalued their products. He thinks the British press is a little healthier. "The quality of writing in the British press is really terrific and the variety is marvellous. In the US, the journalism varies from place to place. If it's a monopoly town it may be second-class. But in New York we've got The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times, which I read every day."

More surprisingly, he is a friend of News Corporation's abrasive New York Post, which he describes as "a really terrific Murdoch tabloid". His relationship with the great media mogul is a complicated one. It was differences with Murdoch on editorial independence that led Sir Harold to give up the editorship of The Times in 1982, after only a year in the post, and head to America. Yet he is clearly an admirer.

Asked for his comment on the view held by some media commentators that falling News Corp profits, the call for online pay walls and the stalling of MySpace suggest Murdoch is losing his touch, Sir Harold pauses and picks his words carefully.

"I think he's far-seeing. The biggest quality of Murdoch is that he doesn't follow the conventional wisdom. He's very courageous. If I had money I would put my money where Rupert's mouth is. I may have lost some with MySpace," he concedes, breaking into a laugh, "but as a general trend I think he's extremely shrewd and extremely well informed – I'm not talking about his political views, I'm talking about his business management."

Though Sir Harold does not "take back a word" of the criticisms of Murdoch's proprietorial methods made in his 1984 memoir Good Times, Bad Times, he describes the subsequent smashing of the print unions in the Wapping dispute of 1986 as a "redemptive blow for press freedom", which led to the birth of The Independent.

The industrial problems that dogged the British press in the 1970s and 80s were another complicated issue for Sir Harold, the son of a Manchester railway worker and active trade unionist. His father nonetheless sympathised with his firm stance towards the likes of the Communist union official Reg Brady, who liked to wear a Russian military fur cap. "I was denied the publication of the Thalidomide story and denied the expansion of the paper, not because we weren't prepared to pay them but because they were bloody-minded," says Sir Harold. He has been impressed by Murdoch's strategy for the Wall Street Journal, since he controversially acquired it from the Bancroft family in 2007. "I was interested to see whether the treatment of China would get more friendly and whether the paper would adopt a certain attitude in news stories. I don't see any malign influence. On the contrary I think that the publisher there, Robert Thomson, has done a first-class job."

His view of the current direction of the BBC is more mixed. "Generally in the US it is highly respected. It is regarded as one of the great British virtues like crumpets and tea," he says, before adding that he regularly hears complaints about the corporation's perceived "anti-Israel" bias at foreign policy events in New York.

Sir Harold is more scathing about the BBC's ambitions beyond its public service remit. "There are probably too many people in the BBC ... and I feel newspapers are entitled to feel resentment that a subsidised corporation is competing with them," he says. "The salaries of the BBC top brass are quite extraordinary."

For all this he remains hopeful for journalism's future, partly because of the achievements of the woman asleep upstairs in their hotel room. Tina Brown, who edited Tatler in Britain and then The New Yorker, launched the news website Daily Beast last year. "You recognise where the title comes from, I hope?" he asks, ever-conscious of journalistic traditions. "Yes, from [Evelyn Waugh's novel] Scoop. Good! My wife's website has more than three million visitors a month now. And what's it based on? Journalism."

There are rumours that Brown may set up a British version of the site, which has grown to a staff of more than 30, including the great investigative journalist Gerald Posner, and has had contributions from Condoleezza Rice and review suggestions from Bill Clinton. "It's not making money now, [but] it will do," says the proud husband. "The question is can a website like that monetise itself sufficiently quickly to replace the diminution in daily journalism – that's an open question and I don't know."

Sir Harold deserves his place in the pantheon of British journalism. Some will say he worked in the final golden era of a story that stretches back, via CP Scott and Harmsworth, Dickens and Hazlitt to the coffee-house pamphlets of the early 18th century. He doesn't see it that way. "Yes I'm optimistic but that's my nature, don't forget. Most times it's worked out, though sometimes not," he says. "But I'd never sit around moaning, I'd be thinking, 'What can I do to change the situation.'" On which positive note, he climbs back onto his sneaker-clad feet and heads off smartly to his next appointment.

My Paper Chase by Sir Harold Evans is published by Little Brown, £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks