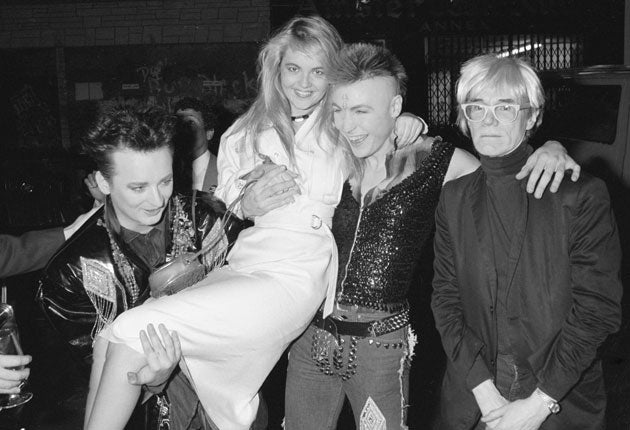

Warhol’s press pass to the stars

As ‘Interview’ approaches its 40th anniversary, Ian Burrell hears how the magazine famous for its celebrity covers was way ahead of its time

Andy Warhol, as one might expect, was no ordinary magazine publisher. He purportedly founded the iconic title Interview merely in order to justify his application for a press pass to give him free access to the New York Film Festival.

But as his reputation as an artist grew, so too did the influence of his magazine. It was nothing for him to secure an on-the-record audience with John and Yoko, as the couple reclined in their bed in Manhattan. And when Interview was granted access to Salvador Dalí, Warhol assigned the story to the flamboyant pre-operative transsexual and film star Candy Darling, simply because he was intrigued by the chemistry the pair would create.

Interview, which will be 40 years old next year, was way ahead of its time in being a magazine devoted to the cult of celebrity, defining the emerging stars of film, fashion, music and literature. It was also the pioneer of the Q&A style of interview, which has become a staple of publishing in the past four decades. And now Glenn O’Brien, who ran the magazine for Warhol in its early years after joining fresh from film school, is back in the editor’s chair.

O’Brien’s latest edition of Interview includes pieces with Damien Hirst, Richard Prince, Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman, some of the most influential artists alive, and the editor hopes it becomes a collector’s item for years to come. “I feel like people are going to keep it on the bookshelf for 10 or 20 years because it’s comprehensive and authoritative,” he says. “It’s not something you throw out it’s a periodical that has the qualities of a book.”

O’Brien came to Interview back in 1970, eight issues after it started. Along with his friend and fellow film student at Columbia University Bob Colcello, he was summoned by Warhol to bring some sense to an editorial operation previously assigned to his acolytes in the wild surroundings of the artist’s studios ‘The Factory’.

“I guess Andy felt that the people who had been editing Interview couldn’t get it done. They wanted more normal people – they used to say ‘nice, clean cut college kids’,” he says. “We really went to work on it and started producing it in a more or less professional manner. It was kind of a dream come true because in undergraduate school we were big Warhol fans, we would be the only people in an audience in Washington DC watching a Warhol film.”

The pair decided to broaden the magazine’s appeal from its origins as an underground film title. “We had the idea of making it more commercial, a bigger and more successful magazine. We decided it should be more a generally cultural magazine and also cover music, art and fashion and other things.”

The early years of the magazine coincided with the emergence of the cassette recorder, a factor which directly influenced the writing in Interview. “It’s no coincidence that Interview came out at the same time as the small cassette recorder. Interview was very much the function of the technology. The most crucial decision that we made was to try to make [the set piece interview] mostly Question and Answer, to really go into a format which nobody had done before,” says O’Brien.

“Playboy interviews, probably the form people knew of before Interview magazine, were highly edited. They would meet with somebody over the course of several days and tape hours and hours and edit it down to something that read in a very cogent, proper copy-edited way. Interview magazine’s interviews were much more verbatim and gave you a feeling of what it was like to be there, like a fly on the wall in the room. It was a lot more free form and a lot less concerned with proprieties.”

The magazine became famed for its covers, which many readers assumed to have been produced by Warhol himself, though, in fact, they were made by his fellow artist and friend Richard Bernstein. “Richard would take the photographs that we selected for the cover and paint them to enhance them. At first it was just livening them up a little, then he developed this poster style. I think probably 90 per cent of people who bought Interview in the late Seventies thought that the covers were by Warhol. [The work] was very much influenced by Andy’s silkscreen style.”

Warhol himself was hovering in the background. “He was very involved in the magazine. He would suggest interviews, if somebody was in town. As the magazine became more successful he became more involved. He had a lot to do so he would delegate responsibility for the magazine but when it came back from the printer if he didn’t like something he would let you know immediately.”

If the interviewee was especially interesting, Warhol would come along. “The high point for me,” says O’Brien, “was when Andy, (film director) Paul Morrissey and I went and interviewed John Lennon and Yoko Ono in bed at their house. That was really fun. It wasn’t difficult at all because Andy knew Yoko from the art world – we just went to their house and they were in their bed. It was very informal and relaxed. We weren’t taken seriously because we weren’t a Time-Life type of publication, we were an underground art magazine run by an artist, so we could go off and get things without going through the whole publicist route.”

Darling’s interview with Dali he remembers as “a very funny interview because a lot of it is not understanding what the other one is saying”. “Andy took Candy Darling because Dali loved extravagant people and Candy was very extravagant.”

Other interviews were equally eccentric, such as one conducted by the pop artist Ray Johnson. “He really wanted to do something for Interview so Andy said ‘OK Ray, you can interview anybody you want’. He came back with an interview with the deputy mayor of Halifax, Nova Scotia. It was really boring but I guess it was pop art you know. I like things like that.”

On another occasion, O’Brien indulged the photographer Berry Berenson, by publishing her verbose interview with Anthony Perkins over several issues. “She went to interview him and I guess she fell in love with him and came back with a 20,000 word interview. She was so desperately in love with this guy that I went and printed it in two, maybe three issues, because I liked Berry and she liked him so it was like a love triangle of publishing. They ended up getting married after that, so it was a historic interview that led to a family.”

Interview was often produced without cover lines, which are so prevalent in contemporary magazine publishing. One edition carried a cover photo of the then little-known Studio 54 disco owner Steve Rubell, without telling readers who he was, a deliberate attempt to give the magazine the feel of a private club.

O’Brien left Interview after four years, by which time circulation had grown from 500 to 35,000. He went to work for Rolling Stone and then High Times, where he wrote a profile of Warhol that led to him returning to Interview as a writer, and remaining there beyond the artist’s death in 1987.

The striking covers of Interview form a part of the current Andy Warhol: Other Voices, Other Rooms exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London. Eva Meyer-Hermann, the curator, says the story about Warhol founding Interview in order to obtain a press pass “may well be true”. “A press pass was found in one of his many time capsules. Warhol never threw anything away.” Meyer-Hermann says the publication was also a vehicle that enabled Warhol to gain access to people he found interesting. “It gave him the opportunity to talk to the celebrities he admired.”

O’Brien returned to Interview as part of a buy-out early this year. He quickly made his mark by securing a revealing interview with Kate Moss. “Kate hasn’t given that many interviews and I have known her since she was a teenager. She was very comfortable and I got her to talk in a way that I think nobody had seen before.”

He is now trying to bring this famous title closer to the origins that he himself helped to define. “I wanted to put it more in touch with the roots. I felt that the content could be stronger and I could raise the level of conversation in the magazine. I thought visually it had become mainstream and bland and I wanted to make it more exciting,” he says. “I think it’s now more like a magazine that Andy would have enjoyed.”

Andy Warhol: Other Voices, Other Rooms is at the Hayward Gallery, London, until 18 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks