How Blackadder changed the history of television comedy

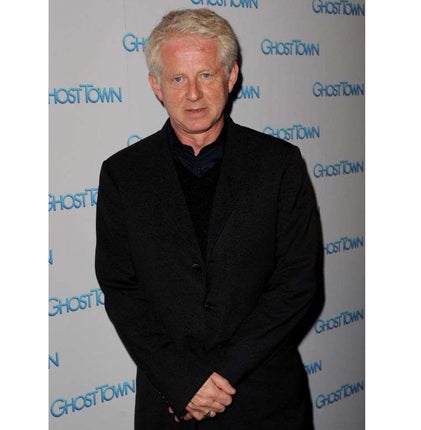

The screenwriter and director Richard Curtis talks to Ian Burrell about his enduringly popular creation

Richard Curtis never expected it to turn out like this – that an idea of toying with the comedy and sheer idiocy of pivotal moments in British history would end up a whole generation later as a hefty, multi-volume resource for teachers.

Blackadder, the most successful historical television sitcom yet conceived, is more than a quarter of a century old. When the blundering Edmund Blackadder, with his absurd pointy shoes, basin haircut and equestrian ineptitude, made his first appearance in 1983 (inadvertently decapitating Richard III at Bosworth Field), Margaret Thatcher was crushing Michael Foot at the polls in real life.

Between mouthfuls of porridge, Curtis, 52, offers his theory on the lasting appeal of the show, which he co-created with its star, Rowan Atkinson. "It seems to have been a trick of fate that something historical finds it easier to last, because it was out of date when it was made," he says.

Since that first medieval incarnation of Edmund, Atkinson has embodied successive generations of the Blackadder dynasty, from the Elizabethan and Regency periods and then, perhaps most poignantly, as an army officer in the First World War trenches. That series – Blackadder Goes Forth – was made in 1989, since when Curtis (who co-wrote the last three series with Ben Elton), has gone on to become a successful screenwriter and film director. While box-office favourites such as Four Weddings And A Funeral, Notting Hill, Bridget Jones's Diary and Love Actually flowed from Curtis's pen, he was also writing another hit television comedy, The Vicar Of Dibley. As his working relationship with Atkinson, a friend from their days at Oxford University, evolved into another endearingly uncoordinated comic icon, Mr Bean, Blackadder appeared to have been consigned to the TV archives – yet it had not gone away.

When Curtis recently returned to Harrow School, where he was once head boy, he was pleasantly surprised to find that the pupils, without exception, asked him not about his blockbusting cinematic romcoms but about a geek of ages past. "They didn't give a damn about the movies," he says.

It is not only at Harrow either. "I think [Blackadder] is taught in schools, definitely the First World War series is. I think teaching might be a slightly rich interpretation of it; I think it is background atmosphere. I've got a feeling that when they do the Regency or the Elizabethan period, at some point after exams or a particularly hard prep, the DVDs go on," he says. "What is great is that they don't think, 'Oh, here's a hideously old-fashioned thing with people with mullet haircuts'. They think 'here's some comedy I like set hundreds of years ago'."

The enduring appeal of the show is helped by the success its stars subsequently enjoyed. Hugh Laurie is now internationally known as Dr Gregory House, while Stephen Fry is almost a national institution. Curtis admits: "When somebody shoves on a DVD, instead of it being people they don't know, it's people they have come across, so it does feel more germane." In recent years, the occasional live Blackadder sketch has kept alive speculation about a fifth series, and Curtis will not rule this out. In fact, he has a fine idea or, as the bumbling Baldrick (played by Tony Robinson) might put it, a "cunning plan". "It did occur to me the other day that it would have been funny to have done a fifth series set when we actually did the first series – in 1984 – with Blackadder working in No 10 and very annoyed about a series called Blackadder which showed his ancestors had been fools."

But Curtis says his concern would be that, 26 years on, he and the team members might be too self-aware and end up "writing to a formula ... putting in lots of similes and lots of silly names". "I have always said that Blackadder was a young man's show about how stupid people in authority were," adds Curtis. "There might be a time when we are all old men and we want to say how stupid young people are. That moment has not yet quite arrived."

Meanwhile, there is another time-travelling television project on his mind. As a father of four children, he has become a big fan of Dr Who since it was revitalised four years ago by the Welsh writer Russell T Davies. "I have been thinking of writing something my children would enjoy," says Curtis. "The fear of films is that you start a film when a child is 14 to amuse them and, by the time you've finished it, they are 17 and wouldn't dream of watching it. So I thought if I actually want to do something that will make my children happy, why not write for a show they do love and which turns itself around quickly, so I can be absolutely confident that I will be sitting in the living room in a year from now, watching something that they'll like."

He has not yet committed himself to writing for Dr Who, though it's a notion that appeals to him. Having been born in New Zealand and lived in various countries before arriving in Britain at the age of 11, his experiences of children's TV are quite different from his those of his peers. "To be honest, I was not really a Dr Who person in its earliest manifestations," he says. "I never really got Blue Peter or Captain Scarlett or Thunderbirds or Dr Who. In a way those are things you've got to start watching when you are five and they then leak into your bones."

Curtis is enthusiastic about the health of British TV comedy, being a fan of The IT Crowd and Flight Of The Conchords and someone who enjoys watching E4's The Inbetweeners with his children. He does voice concerns about children's history books ("it's a tough search to find a Napoleon or Wellington biography in a child-friendly form") and thinks that, although research was never its strongest suit, perhaps Blackadder can help here. "We wrote the whole second series without ever reading a book, but it's a weird thing the amount of history you know in your bones," he says. "After we'd written Blackadder II, I gave Ben a Ladybird book of Elizabethan history for Christmas and it turned out we'd covered 12 of the 13 chapters. Somewhere in your bones, you know there was exploring, beheading, religious corruption, the invention of the cigarette and so on."

He regrets that "kids don't watch old historical movies on wet Sunday afternoons" any more, but maybe Blackadder (which he thinks took its name from a "dodgy" Tony Curtis film called The Black Shield Of Falworth) can fill that void too. "Maybe what we are doing is providing the background buzz of inaccurate historical fiction," he muses.

While there might be a shortage of biographies aimed at young readers, Terry Deary's Horrible Histories series has been a publishing phenomenon, Curtis points out. "It's quite interesting that history education has moved in a Blackadder direction," he says. "It is trying to take the juiciness, violence, stupidity and oddness of old eras to look at it through a young kid's eyes."

Blackadder Remastered: The Ultimate Edition, a deluxe box set of all four series with special features, is out on DVD today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments