Fights, drugs, racial tension: '70s spelled trouble for NBA

If there was a decade when the NBA nearly disintegrated under the weight of its own problems, the 1970s was that decade

Even the biggest games were on tape-delay. Anyone who sat through what the NBA had to offer in the 1970s could see this was a league that struggled with the spotlight.

If there was a decade when the NBA, which turned 75 this season, nearly disintegrated under the weight of its own problems, the 1970s was that decade. It was a fight-filled, drug-addled operation that had made Black players an integral part of the show, only to be left wondering if those players were chasing away the fans.

It featured a plodding brand of basketball that looked even worse when compared to the game being played by the upstart ABA — a free-flowing, 3-point-shooting fun-fest that wasn't above using trumped-up contract deals to poach away some of the sport's most promising talent.

The NBA's 17 teams at the start of the decade were mostly in America's largest markets and were mostly well-financed, which gave the league the bankroll and heft to carry on despite dwindling crowds and a product that, more or less, nobody wanted to watch.

During an era in which the NFL was taking off and Major League Baseball still held a tight grip on the imaginations of American sports fans, chunks of the NBA playoffs and finals were relegated to late-night, tape-delayed broadcasts — a surefire signal of trouble, and a reminder to us now that the league's bright future in the 1980s and beyond was anything but preordained.

Early in the '70s, average attendance hovered at around 8,000 fans a game. The NBA finals received a 7.2 rating in 1979, a time when there were three networks and a 20.0 was only good for 30th place in the Nielsen ratings.

“The fan base was like, 'Ehhh, I don't know if I like this,'" said Spencer Haywood, who won a landmark Supreme Court ruling in 1971 that opened the door for players to enter the league before completing college.

“There was so much chatter about it becoming a Black league,” Haywood said. "And we Black players didn't help the matter. We weren't refined. It was like, big fur coats, big fur hats. It was like Superfly in the NBA.”

The league also had its share of fighters and drug abusers.

Haywood himself used cocaine while with the Lakers in the late '70s — a stint that came to an unceremonious end when he was kicked off the team after falling asleep during practice for a finals matchup against the 76ers.

John Lucas. David Thompson. Bernard King. Michael Ray Richardson. Walter Davis. These were a few of the players who had problems with drugs in a league where, the Los Angeles Times estimated, up to 75% used cocaine and one in 10 smoked, or freebased, the drug.

In an interview with The Associated Press, Haywood said he became addicted at a Hollywood party, when someone took him into a kitchen where they were heating up cocaine for freebase.

"I took a hit off that ball that night at around 10:30," he said. "Next thing I knew, I left there at 4:30 to get home and go to practice. It grabbed me just like that.”

In some ways, the proliferation of drugs, along with the integration of the league, reflected changes that were playing out across society in America. Not all of it could be labeled as progress.

In 1979, the New York Knicks became the first team to have an all-Black roster — an achievement celebrated in some corners but one that also led racists to pervert the team's full name.

“It wasn’t so much New York attitudes, but fans around the league let you know how they felt about you as an opponent and as a Black man as well,” Knicks star Earl Monroe told Newsday in a recent interview.

Meantime, the league had taken a violent turn. Haywood said fights broke out essentially “every other night, and for no real reason.”

If there was a single moment that defined the problem, it came during a game between the Rockets and Lakers in 1977, when Rudy Tomjanovich ran down the court to intercede in a fight. Kermit Washington turned and cold-cocked Rudy T, crumpling him to the floor and fracturing his skull, cheekbone and nose.

But that was hardly the first burst of violence to mar an NBA game, and some of the ugliest incidents came when the lights were brightest, in the finals.

— In 1975, Warriors coach Al Attles, not a man to be trifled with even after his playing days, stormed onto the court and tangled with Wes Unseld as Attles tried to protect Rick Barry after Barry was sucker punched by Mike Riordan of the Washington Bullets.

— In 1976, a fight punctuated Game 3 of the Suns-Celtics series, then a fan assaulted referee Richie Powers, who had earlier blown a potentially decisive call, as part of a wild finish to the triple-overtime thriller in Game 5.

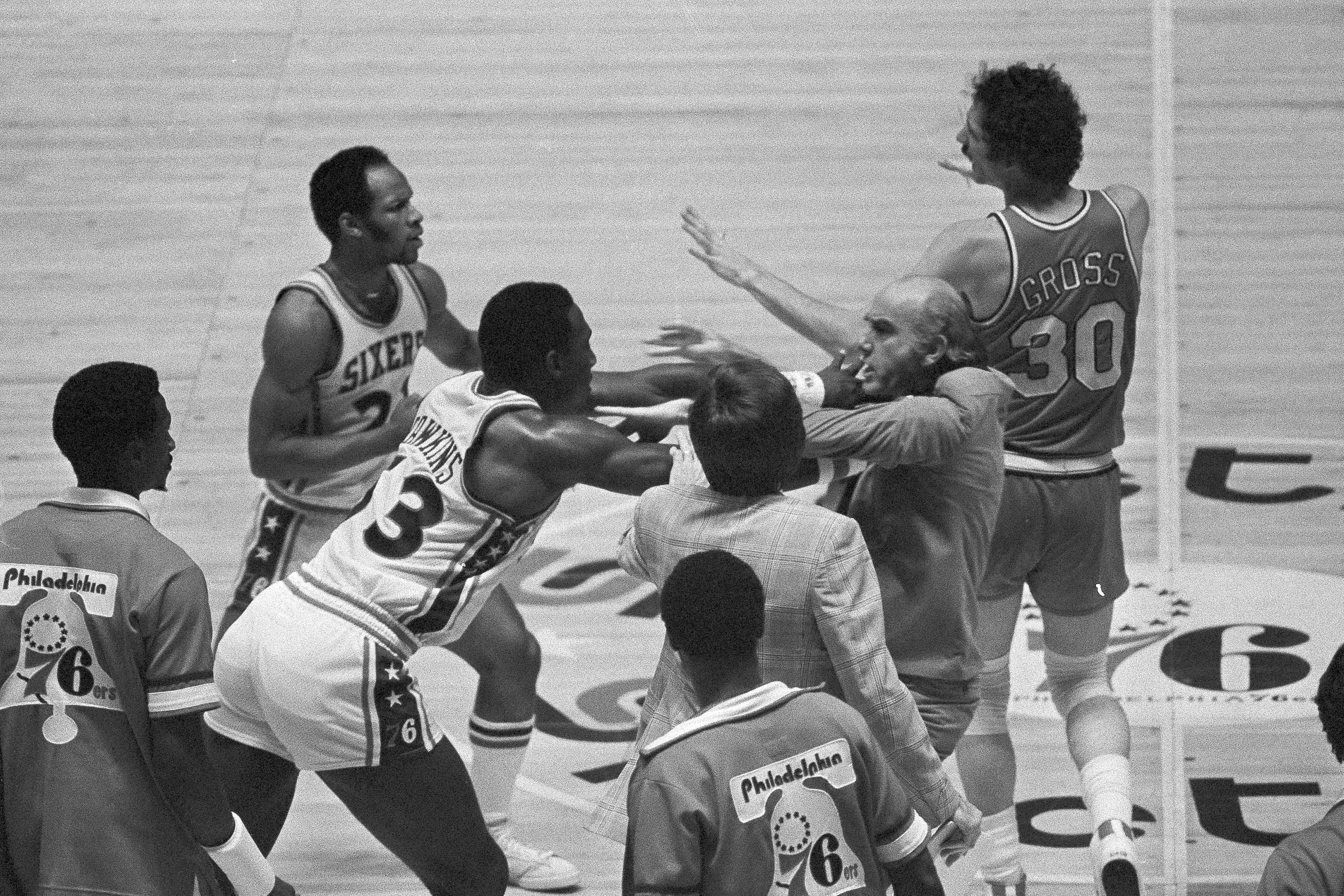

— In 1977, Maurice Lucas and Darrell Dawkins squared off in a fight that changed momentum between the Sixers and Blazers that also brought people from the stands down onto the court.

“To say I was not getting a great reaction from potential sponsors would be the kindest way to frame it,” former NBA executive Rick Welts said in the ESPN documentary “Basketball: A Love Story.” “If I could get an appointment, it was about 15 minutes of 'Why would anyone in their right mind want to associated with your league?'”

Among those asking that question was CBS, which in the late ‘70s began airing many postseason games, including some finals, on tape-delay, as a way of keeping affiliates happy and not impeding on sweeps week, back when the finals started in May. (People much preferred watching “Dallas,” over LA or Philly).

The NBA TV deal was so inconsequential in the ‘70s that the league barely flinched when owner Ozzie Silna asked to forgo a lump-sum payment in exchange for a piece of the NBA’s future TV rights as the buy-off to make his Spirits of St. Louis disappear when the NBA absorbed the ABA’s four best teams in 1976.

"We saw some room for growth there," Silna said in a 2006 interview with The AP, by which time he had become a millionaire hundreds of times over. "We had no idea it would grow this much."

Hardly anyone did in those days, but for anyone willing to look closely enough, there were glimmers of hope.

In the NBA offices, a relatively unknown lawyer by the name of David Stern who had helped the league in its futile Supreme Court fight against Haywood, was moving up the corporate ladder and starting to inject the idea that the league needed a clean-up job and a rebranding.

“We needed someone to come in and put things in order,” Haywood said of Stern, who became commissioner in 1984. “We were at a point where you had to do a number of things to get the drugs out, and to get the fighting out.”

As for that clinching game of the 1979-80 NBA Finals between LA and Philly that most of the country watched on delay, or missed altogether: It featured a rookie named Magic Johnson. Playing center in place of the injured Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Johnson went for 42 points and 15 rebounds to put away the 76ers.

Across the country, rookie forward Larry Bird was a spectator. Despite Bird's 22 points a game, the Celtics had lost in the conference finals to Philly and Doctor J. Only a year earlier, Bird and Magic had met in the NCAA title game between Indiana State and Michigan State. It was just that sort of star-studded matchup the struggling NBA desperately needed to be able to showcase, as well, if it was to ever regain its footing.

___

More on the NBA At 75: https://apnews.com/hub/nba-at-75

___

More AP NBA: https://apnews.com/hub/NBA and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks