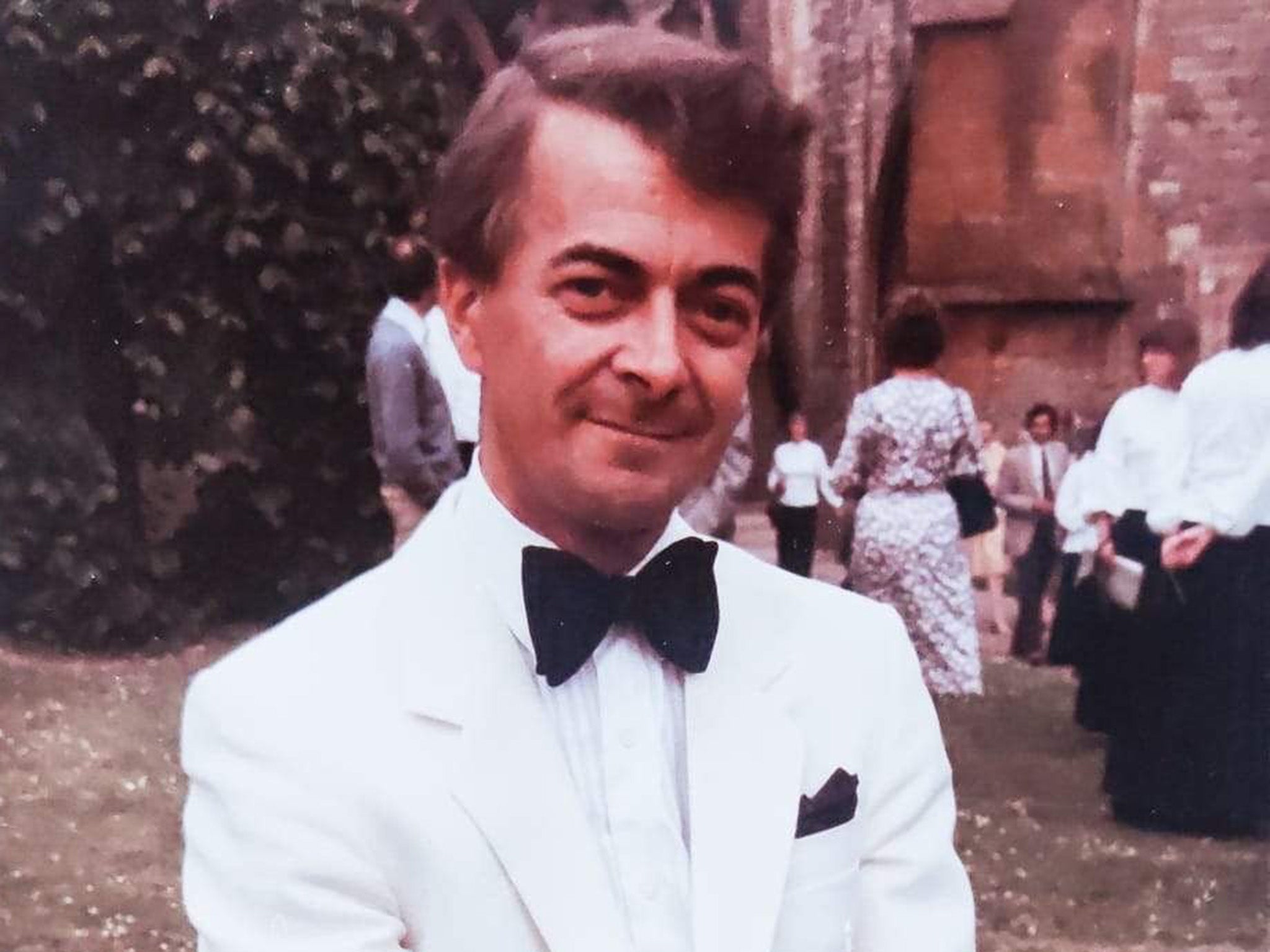

Barry Griffiths: Violinist who led some of the nation’s finest orchestras

He effortlessly built an enviable reputation for musical insight and selfless integrity

Barry Griffiths, one of a series of distinguished musicians produced by the Royal Manchester College of Music throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, enjoyed an outstanding reputation as a soloist, chamber musician and teacher, in addition to becoming leader of three of this country’s premier orchestras.

He invariably enjoyed an easy rapport with audiences and fellow musicians alike, and if his reputation has not reached the heights of some of his peers, it is perhaps because he displayed a notable lack of ego. For him, virtuosity meant artistry, not showmanship.

The only son of a Birmingham butcher, Barry Warwick Dominic Griffiths began his illustrious career studying the piano at the age of six before, four years later, taking up violin lessons with local teacher Kenneth Page. By then he had also become a prolific composer, having a number of his early piano pieces broadcast on the BBC Children’s Hour programme. At the same time, he directed a local music club that, most unusually, was run entirely by children. In 1955, at the age of 16, he proved a natural and popular choice to become the first leader of the newly formed Midland Youth Orchestra, rehearsing at that time in the old Birmingham School of Music.

Twelve months later, Griffiths was awarded a John Webster Memorial Exhibition scholarship to move north and study at the Royal Manchester College of Music. There his violin tutor was the celebrated Hungarian virtuoso Endre Wolf, and his piano teacher was Dora Gilson. They instilled in him the academic rigour that not only characterised his subsequent career but, in the more immediate short term, brought him a whole raft of awards that included the prestigious Webster Memorial Prize together with the highly coveted Hiles Medal. When fellow student Rodney Friend left Manchester to join the London Mozart Players, Griffiths succeeded him as leader of the college orchestra.

Emerging as one of the finest violinists of his generation, Griffiths effortlessly built an enviable reputation for musical insight and selfless integrity. Musically adventurous, precise and flawless, his virtuoso playing rarely failed to make an impact. Long noted for his ability to obtain a singularly beautiful tone, he revelled in the opportunities afforded him by the acquisition of a magnificent violin built in 1861 by the Parisian instrument maker Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume. A companion throughout the violinist’s career, the instrument went missing in 1994 when Griffiths was rushing for a train at London Bridge station. He was devastated but, thanks to the police, it was quickly returned to him.

Remaining in Manchester after graduating, Griffiths was soon enjoying a busy and successful freelance career. Invited to return to the Royal Manchester College of Music to teach, for 10 years he led Manchester University’s Ad Solem Ensemble as they explored all manner of mainly classical and romantic chamber repertoires. Membership of George Hadjinikos’s New Manchester Ensemble saw him no less at ease with more rarefied contemporary works, including a number of impressive premieres. Likewise, having joined the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra in 1964, he was rarely off the airwaves. His elevation to leader in 1972 brought his talents to a far wider national audience.

Four years later, Griffiths moved south to become leader of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. He was a regular soloist throughout his time in post and popular pieces included both Edward Elgar’s Violin Concerto and Ralph Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending, a work he later put on disc. Other recordings range from the ballet scores of Tchaikovsky to the music of Carl Davis. He was no less successful in managing to diffuse the often bitter tensions between fellow players and the more combative of conductors, most notably the fiery Antal Dorati. Particularly sensitive to mood, he was always quick to appreciate difficulties and even quicker to give colleagues support.

Becoming leader of the orchestra of English National Opera in 1989, Griffiths remained with them until retirement in 2004. He was appointed an OBE in 2002 for his services to music. As a conductor, he appeared rarely with professional bodies, but an exception was the ENO’s 1995 revival of Nicolette Molnar’s production of Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte. However, with amateur groupings such as the Voce Ensemble and the Lydian Orchestra, he proved highly efficient, leading each with unfailing good humour and inexhaustible enthusiasm.

While studying at the Royal Manchester College of Music, he met fellow violinist Angela Caldwell. They married in 1964, and together with their eight children – Clare, Francis, Katy, Peter, Cecilia, Dominic, Antonia and Susanna – proceeded to make up one of the country’s most talented musical families. With no television in the house, each child first learnt the piano before progressing on to an orchestral instrument. Regularly performing together over the years, this family ensemble helped raise many thousands of pounds for numerous Kent charities. His wife survives him as do the children.

Barry Griffiths, musician, born 20 May 1939, died 17 September 2020

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks