Beth Chatto dead: Garden designer and writer who won 10 golds in a row at the Chelsea Flower Show

The Beth Chatto Gardens in Essex has become a place of pilgrimage for many thousands of admirers and enthusiasts

Creating a garden demands above all an appreciation of climate and landscape and the limitations they will place on what can be attempted.

Beth Chatto, who has died aged 94, found herself faced with the formidable challenge of establishing one in a predominantly arid and windswept location, inimical to many of the best-loved elements of a conventional English garden.

It took patience and determination; but in the end she succeeded so spectacularly that she achieved national celebrity and the Beth Chatto Gardens, at Elmstead Market in Essex, has become a place of pilgrimage for many thousands of admirers and enthusiasts.

Chatto never strayed far from Essex. Born there in 1923, she was educated at Colchester County High School before going to Hockerill Teacher Training College, just across the border in Hertfordshire.

While she did not take up teaching as a career, the skills she learned at college would come into their own later when, as an established star of the horticultural firmament, she was in demand as a lecturer and instructor in Britain and abroad, travelling frequently to Europe, America and Australia.

She became interested in gardening at the age of 20 when she married Andrew Chatto, who had made a study of plant associations. The first skill she developed was as a flower arranger, and she was a founder member of the Colchester Flower Club. Early on she was inspired by Sir Cedric Morris, the plantsman and artist whose nearby garden at Benton End in Suffolk showcased his unerring eye for shape and colour.

After the Second World War Andrew established a fruit farm at Elmstead Market, five miles east of Colchester. By 1960 he was successful enough to have a house built for the family – by now he and Beth had two daughters – in a corner of the farm that had become a wilderness, near a spring-fed stream too wet and boggy to sustain an orchard.

Although the banks of the stream were a tangle of trees and shrubs, Chatto was excited by the challenge of making a garden at their new home. Essex is one of England’s driest counties, with an average annual rainfall of below 20 inches, and she calculated that the irrigation from the stream would allow her to experiment with a wider range of plants than her neighbours. “I thought it would be wonderful to be able to grow primulas and hostas and so on, which are normally hard to grow round here,” she told me in her garden in 1996.

Water from the adjoining fields drained into the stream, and the spring ensured that it flowed even in the driest weather. She dammed it to create three ponds, placing around the edges groups of damp-loving plants such as arum lilies, gunnera, skunk cabbage and snake’s head fritillaries.

She planted willows, birches and swamp cypresses to give structure to the garden, supplementing the oaks – some quite ancient – that were already there.

Moving away from the stream, visitors passed through the woodland garden, where shade-loving plants such as hellebores thrived beneath the oaks. Here Chatto’s genius for grouping plants came into its own, with an emphasis on their foliage: yellowy green leaves merging into bronze and gold, with billowing grasses and ferns – of which she was especially fond – drawing the eye from one group to the next.

“I’m interested in harmony in foliage, in making things flow,” she told me. “I like plants that set each other off and I keep out those that I think look aggressively cultivated. A garden is a matter of selection, of choice. It’s like painting. Everyone may have the same palette but they all do it slightly differently.”

Closer to the house is the unshaded Mediterranean garden, for species that need minimal quantities of water. Here again the planting and structure is meticulous, with tall shrubs such as cistus and buddleia providing the framework for such subjects as verbascum and kniphofia. She made maximum use of whatever moisture there was by a generous application of mulches, chiefly bark.

This provided the material for her first book, The Dry Garden, published in 1978. It was followed four years later by The Damp Garden and, as her reputation grew, a stream of other books appeared every three or four years – all written in longhand to be transcribed by her secretary. She wrote attractively and informatively, with a keen eye for detail, while never aspiring to be ranked among the great stylists of garden literature such as EA Bowles, Vita Sackville-West and her good friend Christopher Lloyd.

Still, in 1998 the Garden Writers Guild gave a her a lifetime achievement award. She carried on publishing in later life with books such as A Year in the Life of Beth Chatto’s Gardens (2012) and 2016’s Drought-Resitant Planting.

By 1967 she had developed sufficient confidence in her horticultural techniques to start a plant nursery, specialising in herbaceous perennials.

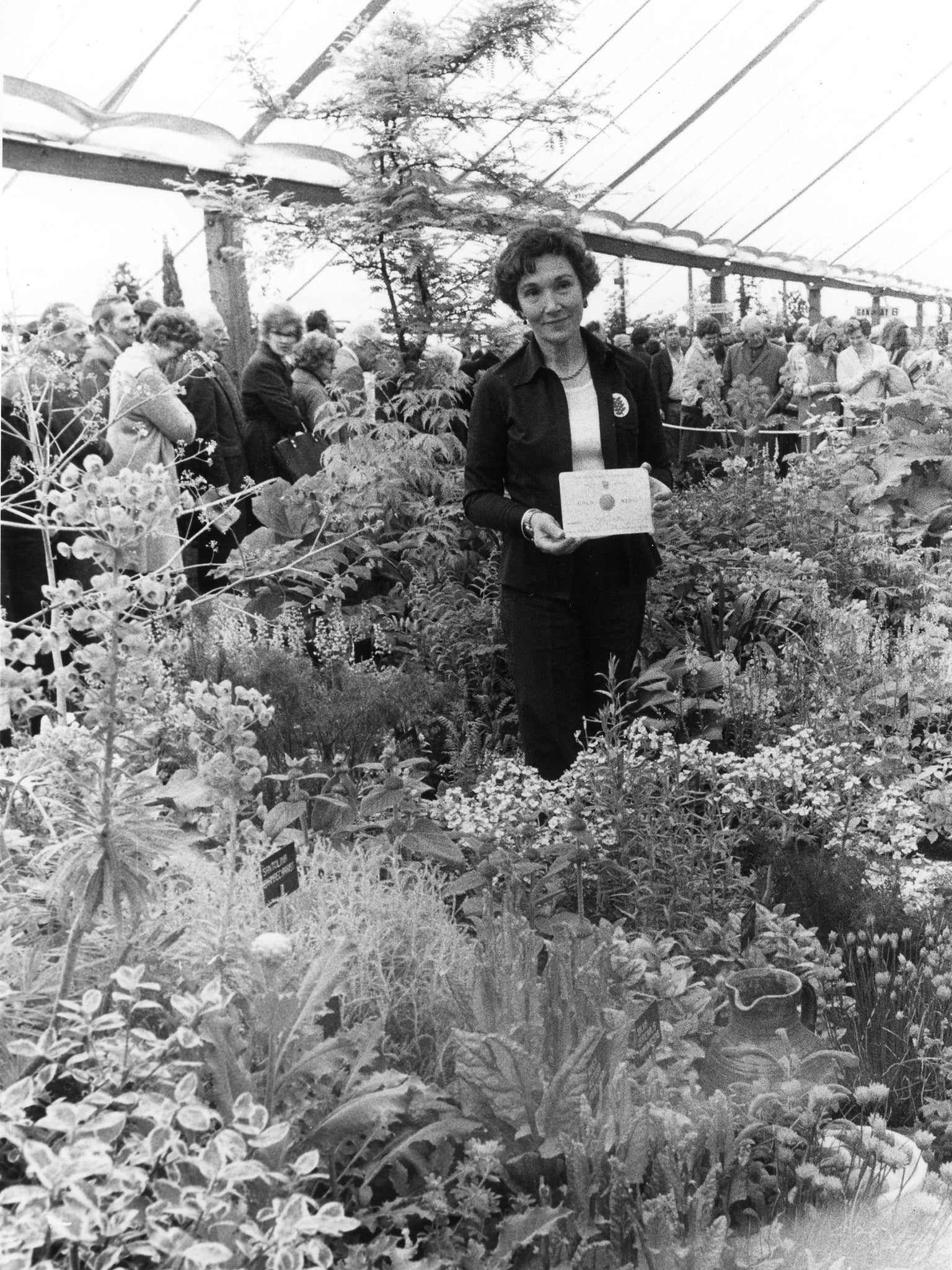

It quickly became a commercial success and eventually the main family business, attracting an increasing number of visitors to the garden. For years the nursery was a regular exhibitor at the Chelsea Flower Show, winning 10 successive gold medals.

In 1988 she wrote a poignant account of the pleasures and pressures of preparing and running a Chelsea exhibit, concluding: “We need all the enthusiasm expressed for our stand; it affects us like champagne when we have been talking, taking orders, giving advice, selling catalogues ... for hours, it seems, on end. Just when we think that we are totally drained, a particularly sympathetic visitor not only gives us a great lift, but kindles enthusiasm ... We all have a great laugh and everyone feels revived.”

This was typical of the warmth and generosity she showed to visitors to her garden. She was unfailingly courteous and patient, even to those who persisted in asking what to her must have seemed very basic questions.

As the nursery grew, Chatto was able to hire more staff to help her run it, but she always took a hands-on approach and loved walking round the greenhouses and sheds to check on the plants’ progress. Her employees welcomed her visits, for she would invariably offer encouragement and congratulation on their efforts.

In 1991 she made the bold decision to move the nursery car park, which had been on the highest and driest part of the estate, and replace it with a gravel garden. This was an even greater challenge than the Mediterranean garden. With water shortages becoming more frequent, and the supply companies banning the use of hosepipes, she thought it would be an important service to gardeners everywhere to identify plants that would survive with the very minimum of moisture.

For that reason she was adamant in refusing to water any part of her garden, arguing that if plants perished she would have established that they were unsuitable for the location.

“I’m discovering what I can grow that will stand the cold of winter and the heat and drought of summer,” she told me. “I hope that by discovering plants that can survive those conditions, I’m doing something to help people who have hosepipe bans.”

Visitors occasionally complained about the parched look of the gravel garden but she stuck to her guns, even when the formidable Christopher Lloyd took issue with her. In a series of letters exchanged between them, published as Dear Friend and Gardener in 1998, Lloyd wrote: “When I see plants suffering, it’s like having a pet animal that you’ve neglected to feed.”

Her reply was uncompromising. She admitted that she had suffered anguish at the height of the drought, but any sentimentality was outweighed by her passion to experiment and learn, reinforced by her conviction that nature knows best. She noted that in the driest periods the gravel garden “remained furnished with interesting shapes, textures and tones of scented foliage”, even if there were few flowers.

This essential difference in their approaches to gardening did not weaken her friendship with Lloyd, which lasted some 30 years until his death in January 2006. They sometimes travelled abroad together and visited the opera at Glyndebourne. In his 1995 book, Other People’s Gardens, he wrote of her: “She is a great proselytiser and a great teacher and she teaches by example, giving the world ample opportunity to profit from her abundant and evident creativity.”

Her husband Andrew died in 1999 and although she had to devote an increasing amount of time to caring for him, she still maintained her lively and active interest in the nursery and the garden. In 1988 she had been awarded the Royal Horticultural Society’s Victoria Medal of Honour and in 2002 she won wider recognition by being made an OBE.

In 2014 she won the John Brookes Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society of Garden Designers.

Speaking to Martha Kearney on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour in 2008, when a retrospective of her work was on display at the Garden Museum, she said she saw herself as part of a tradition. “I’m only part of a chain of people who’ve influenced me ... now all the people who come here who take little bits of me away, if you like,” she said, adding: “We’re all handling the same plants.”

Her garden was her life and will now be her memorial. The last word should go to Christopher Lloyd, again writing in Other People‘s Gardens: “So many of the most admirable enterprises depend on the gifts of one person and her admirers must learn from them while they may ... I salute her with love and with admiration.”

Beth Chatto, garden designer and writer, born 27 June 1923, died 13 May 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks