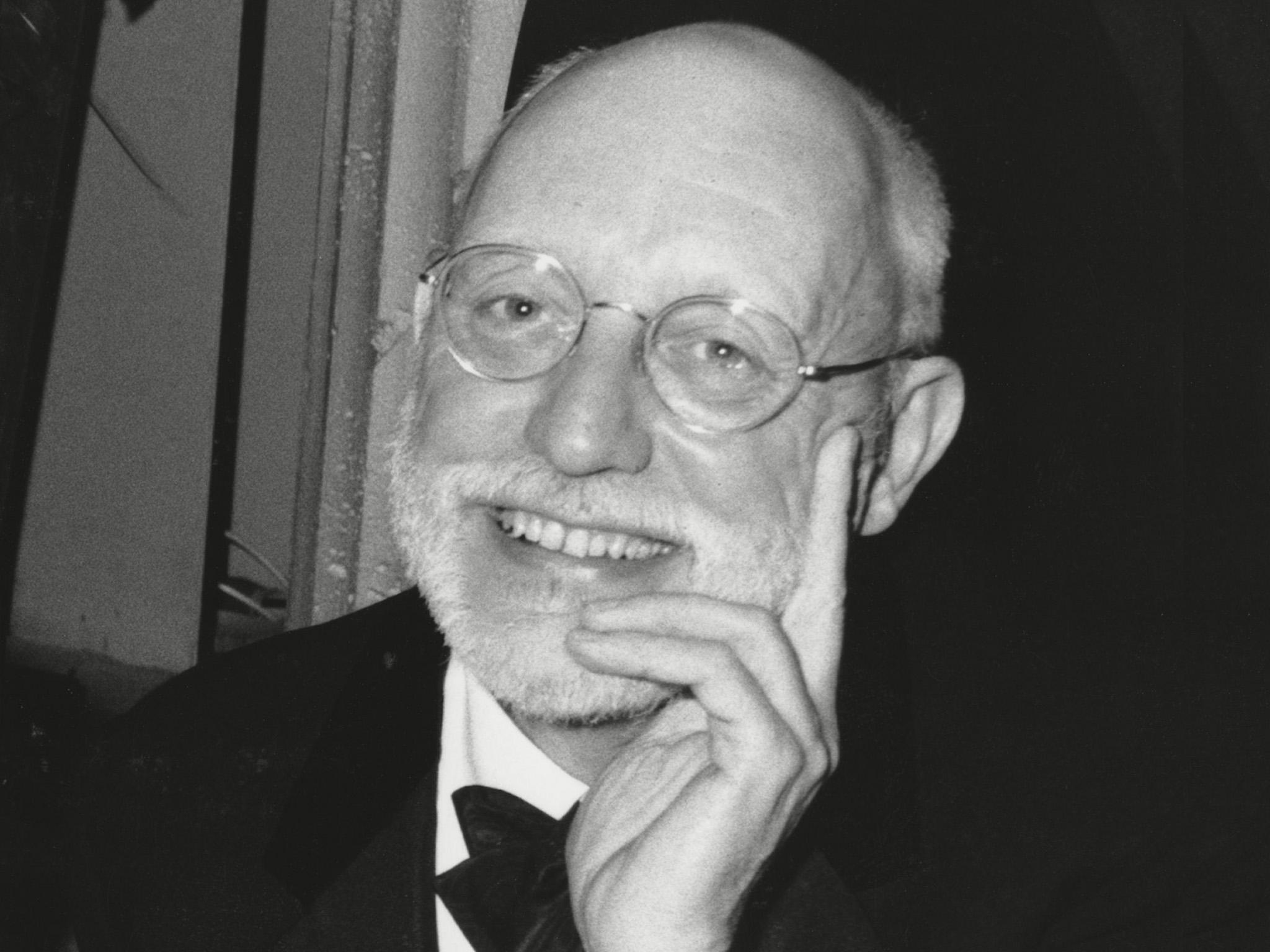

Charles Wood: Playwright and screenwriter whose military experience informed his work

He also scripted key Sixties movies such as ‘The Knack’ and The Beatles’ ‘Help!’

Charles Wood, who has died aged 87, was a writer for stage and screen whose brilliant and idiosyncratic use of language was wedded to an iconoclastic, passionate humanism.

Wood was born to a pair of touring actors, Jack Wood and Mae Harris, in Guernsey in 1932. Acting didn’t appeal to him and he attended Birmingham Art School, then in 1950 joined the army, serving for five years in the 17th/21st Lancers. His military experience would inform much of his later writing.

Wood worked as a graphic artist and scenic designer in London, including backstage at Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop, but found himself getting more interested in the words. His first one-act play, Prisoner and Escort (1959), was performed first on the radio, then on stage and television.

His first full-length piece, Dingo (1967), was to be performed by the National Theatre in 1961 but the Lord Chamberlain’s office objected, thinking it subversive (which shows an astuteness rarely found in censors). By the time the play made it to the stage in 1967, Wood was already writing for films.

The break came when Woodfall Films wanted to adapt Ann Jellicoe’s dazzling sex comedy The Knack. Richard Lester, fresh from the success of A Hard Day’s Night, was in the director’s chair, and he and Wood forged a friendship for life and a working partnership that endured across multiple projects.

By exploding the source play and reassembling it with his own additions, Wood helped to make The Knack… and How to Get It (1965) a groundbreaking film that introduced “Swinging London” to the screen and scooped the Palm d’Or at Cannes. Wood’s fragmented language, non-sequiturs, double-talk and gobbledygook blended beautifully with Lester’s jump-cuts, fast-motion and freeze-frames. Cinema and language were being joyously taken to bits.

Wood scripted Lester’s second Beatles film, Help!, a pop-art caper, released the same year, and in 1967, as Dingo was finally being staged, wrote the blistering, Brechtian satire How I Won the War, which featured John Lennon and was referenced in the lyrics of the song “A Day in the Life”. “Every word of this film is written in pencil in my own handwriting,” proclaims the hero.

In 1968 Wood’s screenplay for The Charge of the Light Brigade, perhaps his biggest project, was filmed by Tony Richardson. Wood’s dialogue, written in a dense, syntactically eccentric style influenced by Thackeray, contributed hugely to the film’s sense of history mixed with the absurd. “I’m an old man, Airey, and I’ve only got one arm. To fight the war with, it won’t be enough, eh?” mourns John Gielgud as Lord Raglan.

The play H; Being Monologues at Front of Burning Cities (1969) dealt with the Indian mutiny, and managed to be epic in both the Brechtian and David Lean senses of the word. The stage directions called for an elephant, which the National Theatre dutifully constructed, and an execution by cannon fired right into the audience’s faces, which the lawyers stepped in to prohibit.

The play Veterans; or, Hair in the Gates of the Hellespont, staged at the Royal Court in 1972, riffed on the experience of filming The Charge of the Light Brigade in Turkey, and enabled John Gielgud, who had appeared in it, to send himself up with Mock Turtle solemnity. “Day after miserable day I walloped about on a carthorse sticking a sword into astonished people: I can’t honestly say I enjoyed it.”

In parallel with his fiery, complacency-shattering film and theatre work, Wood enjoyed a television career which often assumed a cosier tone. He had long collaborations with the actor George Cole, for whom he wrote TV plays and then a sitcom, Don’t Forget to Write! (1977), drawing upon his own life as a procrastinating author and family man, and with John Thaw, for whom he wrote powerful episodes of Morse, Kavanaugh QC and Monsignor Renard. He also scripted three swashbuckling yet sombre episodes of Sharpe from 1994 to 1997.

It was the Bafta-winning TV play Tumbledown (1988), dealing with a soldier (Colin Firth) seriously injured in the Falklands, that began a film collaboration with director Richard Eyre, a longtime theatre friend, leading to Iris, the Iris Murdoch biopic starring Judi Dench in 2001, and the thriller The Other Man, with Liam Neeson in 2008.

Eyre wrote of Wood: “There is no contemporary writer who has chronicled the experience of modern war with so much authority, knowledge, compassion, wit and despair, and there is no contemporary writer who has received so little of his deserved public acclaim.”

Settling in the north Cotswolds, Wood may have joked about being a “recovering writer”, but he never really stopped, tinkering with old plays or new ones until his final illness.

He is survived by his wife, the former actor Valerie Newman, and his daughter Kate, also a screenwriter. A son predeceased him.

Charles Wood, playwright and screenwriter, born 6 August 1932, died 1 February 2020

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks