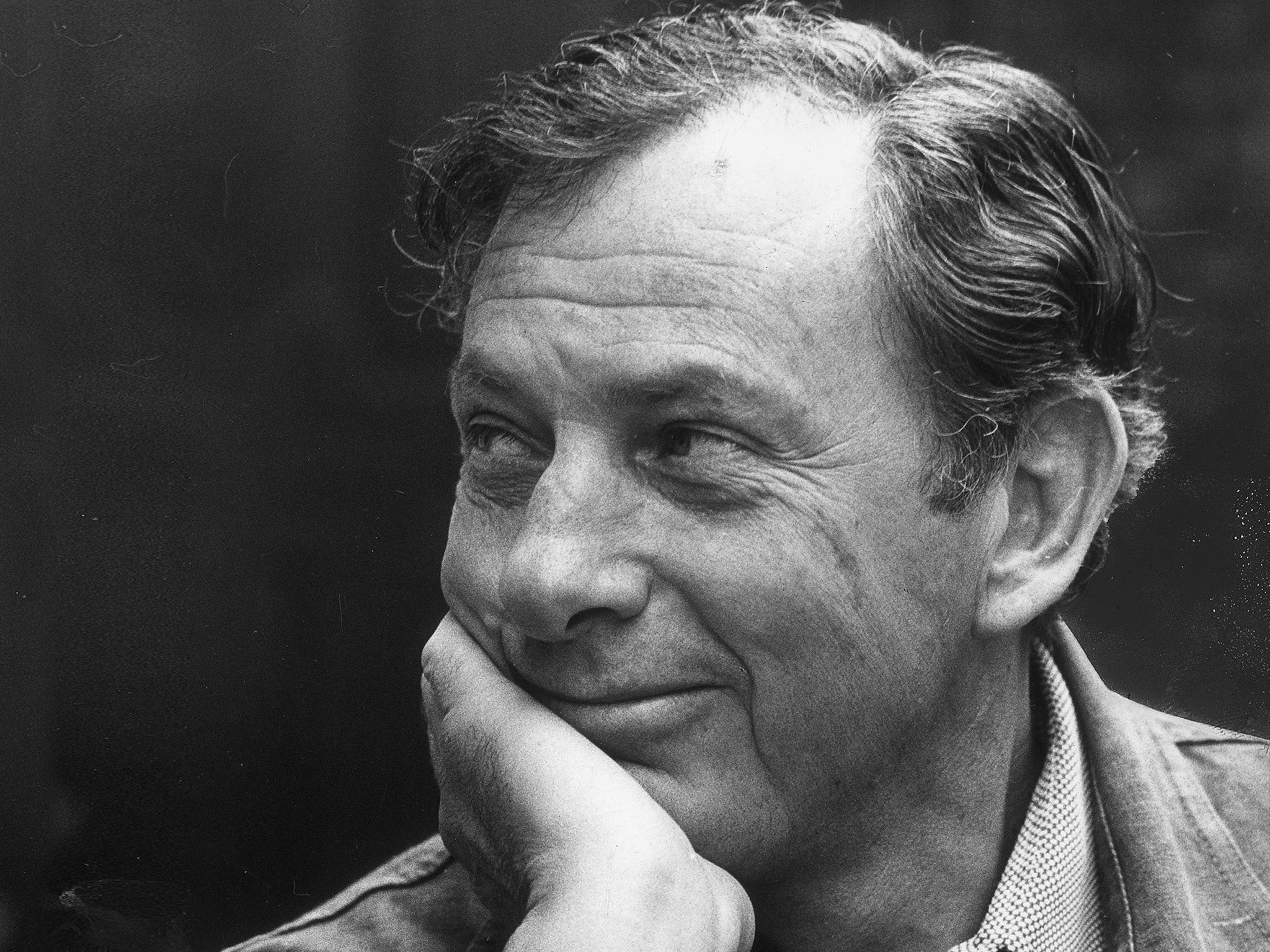

Clifford Irving: Author whose literary hoax fooled America in the Seventies and inspired a Hollywood film

Irving penned a fake autobiography of Howard Hughes, the American billionaire and eccentric recluse. It was so good that when Hughes complained, many thought he was the liar

One of the greatest literary hoaxes of the 20th century – call it a prank, scandal, adventure, criminal conspiracy, or an early piece of “fake news” – fooled lie-detectors, handwriting experts, publishers, journalists, Swiss bank officials and very nearly the entire United States.

It featured disguises, an arcane codename, the world's most reclusive billionaire and, almost by chance, a president. By some accounts, it may have triggered the break-in at the Democratic National Committee which led to the Watergate scandal that brought down Richard Nixon.

The hoax's perpetrator? Clifford Irving, the globetrotting novelist and supposed biographer of the late American billionaire Howard Hughes. Hughes was known for being an eccentric and a recluse – perfect fodder for the plan Irving was to hatch.

Irving, who has died aged 87, had lived nearly as swashbuckling a life as Hughes when he contacted publisher McGraw-Hill in early 1971, declaring that he had obtained Hughes's permission to write a tell-all biography of the aviator and movie mogul.

The son of a prominent New York cartoonist, Irving had worked as a New York Times copy boy, machinist and door-to-door cleaning supplies salesman before sailing around the world, living on a houseboat in India and riding on horseback into Tibet. He wrote novels, reported on the Middle East for NBC and moved to Ibiza, where he met three of his six wives and became a local celebrity, using pictures of Henry Miller and William Burroughs for target practice with his air pistol.

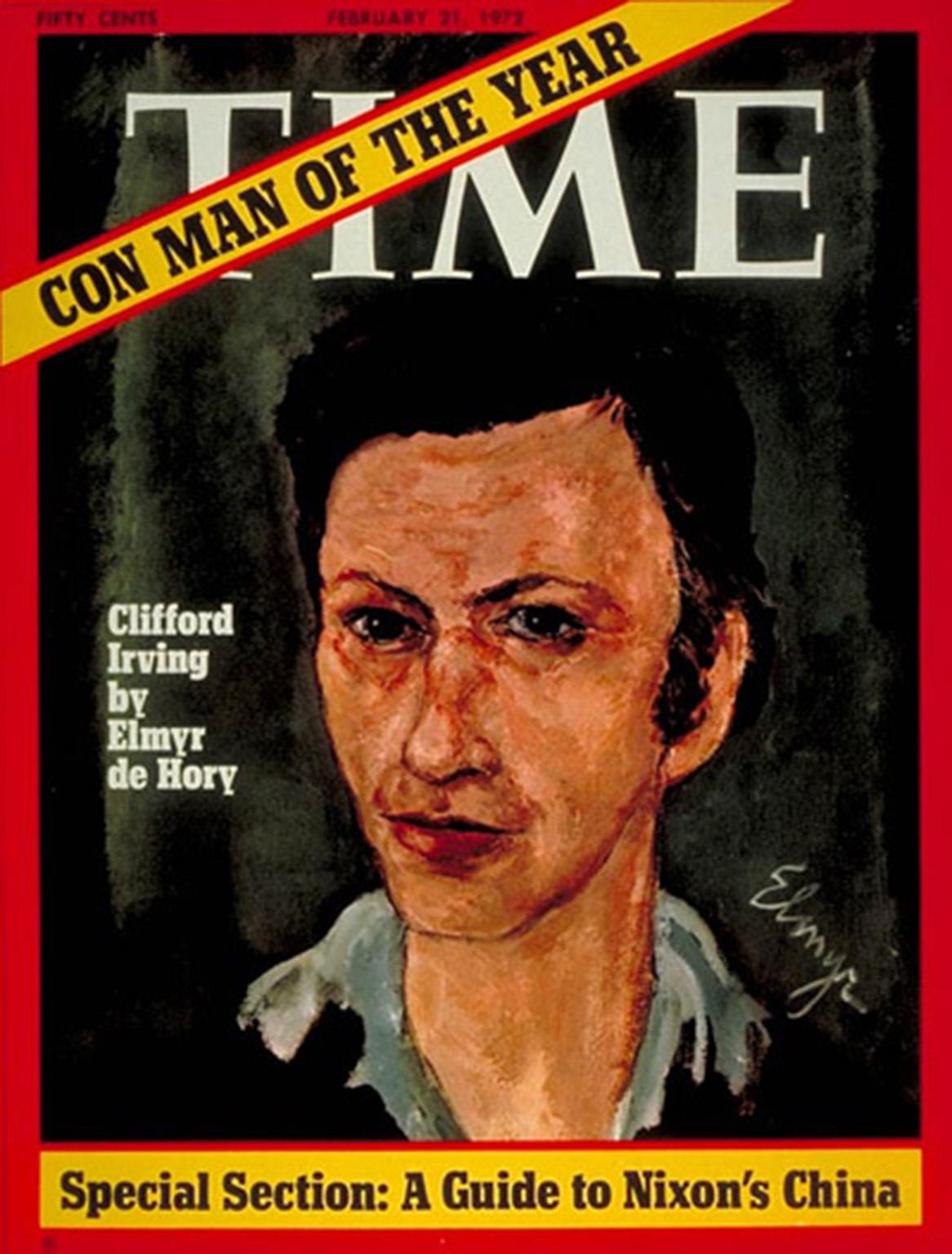

His act of literary forgery was inspired by a neighbour on the island, Hungarian art forger Elmyr de Hory, who became the subject of Irving’s book Fake! (1968). Sometimes described as a novel – as with much of Irving's life and work, the lines between fact and fiction were blurred – the book chronicled de Hory’s career, creating sham works by Picasso, Matisse and Modigliani and inspired the Orson Welles film F for Fake.

In a letter to his publisher, Irving said that he had sent a copy of Fake! to Hughes, who was reportedly living in near-total isolation inside a hotel in the Bahamas. The billionaire, he said, replied with a thank-you note praising Irving's sympathetic treatment of the subject, which Irving took as cue to suggest a biography of Hughes himself.

Irving assumed that Hughes had become so reclusive and private – he had not been seen in public for 15 years – that he would rather stay silent than come forward and deny the book was real. He soon received a staggering $750,000 advance from McGraw-Hill and a sizeable check from Life magazine, which planned to publish excerpts from what became known as Autobiography of Howard Hughes.

With the help of a researcher and co-author, Richard Suskind, Irving began studying the details of Hughes's life, gathering old news stories and reference materials. The duo took turns “interviewing” one another, pretending to be Hughes as they transcribed imaginary conversations in which the movie producer described his friendship with Ernest Hemingway (fake) and his efforts to perfectly capture the breasts of actress Jane Russell on film (real).

Irving travelled to Mexico, Puerto Rico and the Bahamas to “meet” with Hughes in parked cars and motel rooms – much of the time he was actually seeing his lover, Danish singer and actress Nina van Pallandt, and placed international calls to his publisher to create a heightened air of authenticity.

He studied examples of Hughes’s handwriting to forge letters by the billionaire, encouraging the book's publication; appeared on 60 Minutes to try to convince sceptics the biography was real; and was aided throughout by his wife, the former Edith Sommer, who used a false passport to deposit the publishers' fees in a Swiss bank account under the name HR Hughes.

“I've read the Hughes manuscript, and it's good, very good,” she told reporters who visited the Irving family home in Ibiza. “It's so good it's a shame it's an autobiography.”

By late 1971, however, Hughes and his lawyers had apparently had enough of the story and announced the book was fraudulent.

Even then, Irving nearly succeeded. Hughes had such a reputation for reclusive eccentricity that some journalists theorised that the billionaire, not the writer, was lying. Perhaps, the theory went, Hughes had agreed to be interviewed for the book but later decided that it would compromise his finances and reputation.

The story fell apart entirely in early 1972, just before the book's scheduled publication, when investigators linked Edith Irving to the Swiss bank account and after van Pallandt, his Danish mistress, announced that she had been with Irving on some of the dates he allegedly interviewed Hughes.

Irving, his wife and Suskind returned the remainder of the money they made during the what Irving later called the “writing event!” and pleaded guilty to charges of grand larceny and conspiracy. Each of them spent time in prison, with Irving serving about 16 months of a two-year sentence. (His wife was also imprisoned in Switzerland for her role depositing the cheques; they divorced after her release.)

Serving time came as a shock to Irving, who was dubbed “Con man of the year” in a Time magazine cover story and insisted that his “autobiography” –“the most famous unpublished book of the 20th century” as the International Herald Tribune put it – was merely a joke.

“I don't see it as a crime worthy of society's customary revenge,” he later said. “Had I succeeded, no one would have been hurt … If I had it all to do over again, I would do it all, with one difference. I would succeed.”

According to Irving, Hughes’s biographer Michael Drosnin “claimed that the threat of the book’s publication caused the White House to worry enough about Hughes’s revelations of bribery for President Nixon to approve the Watergate break-in.”

Born in Manhattan, Irving graduated from Cornell in 1951 and soon travelled to Europe, where he completed the first of some 20 novels and works of non-fiction, including the legal thriller Trial (1990) and Clifford Irving: What Really Happened (1972), which was later reissued as The Hoax. Written by Irving and Suskind, the book chronicled the making of their Hughes work, and was adapted into a 2006 movie starring Richard Gere and Alfred Molina.

Irving is survived by his wife of 19 years, the former Julie Schall of Sarasota; three sons from earlier marriages; and one grandson.

He offered different explanations in later life for why he decided to write the Hughes book, but eventually pointed journalists toward the epigraph to his book The Hoax, a quote from someone named Jean le Malchanceux.

“You may look for motive in an act, but only after the act has been committed,” it began. “An effect creates not only the search for a cause, but the reality of the cause itself. I must warn you, however, that the attempt to establish relationships between acts and motives, effects and causes, is one of the most time-wasting games ever invented by Man.”

Irving told a newspaper in 2007 that the quote was from a “12th-century French philosopher” before pausing to correct himself.

“Actually,” he said, “I made him up.”

Clifford Irving, writer, born 5 November 1930, died 19 December 2017

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks