Dave Charnley: Boxer considered one of the best without a world title

When Dave Charnley was asked to pick the best fighter he ever met he was invariably stuck for an answer and would mumble something polite about there being "so many". Charnley held the crown no fighter ever wanted when the great Mickey Duff declared him the best British fighter never to win a world title. "It was certainly not through a lack of trying," gentleman Dave would reply. Charnley also held the British, European and Commonwealth lightweight titles.

In the early 1950s in south London, fighting for England and being the ABA champion meant a lot and Charnley enjoyed what many called a reign of terror during his years at the Fitzroy Lodge. He won the ABA featherweight title in 1954, stopping Dick McTaggart in the final in the first round; McTaggart won Olympic gold two years later.

Charnley turned professional with Arthur Boggis, a man with a justifiable and fearsome reputation for getting the most for his fighters at the negotiating table. However, Boggis was also one of the bravest managers working at time when there was, if the truth be told, a lot of competition for that title.

There was far less protection for fighters in the '50s and Charnley never had it easy. He lost a couple and drew one before winning the British title from Joe Lucy in 1957, a title he kept until he retired in 1964; Charnley's fighting reputation was made far from the lasting glitter of the Lonsdale belt.

In 1958 he met a trio of exceptional fighters: Don Jordan, Peter Waterman and Carlos Ortiz. On each occasion Boggis went to work, helping Charnley accumulate a small fortune in fights a modern manager would not consider for a young star. Jordan beat Charnley over 10 rounds and 11 months later won the world title at welterweight, Ortiz beat Charnley over 10 and eight months later won the world title at light-welterweight and Charnley stopped Waterman in five; Waterman was the reigning British and Commonwealth welterweight champion, a full 11lb heavier.

"There were a lot of good fighters at the time and it was not unusual for a fighter to move about the weights," said Duff. "Charnley was the best British fighter to not win a world title and the truth is that he survived his career despite Boggis."

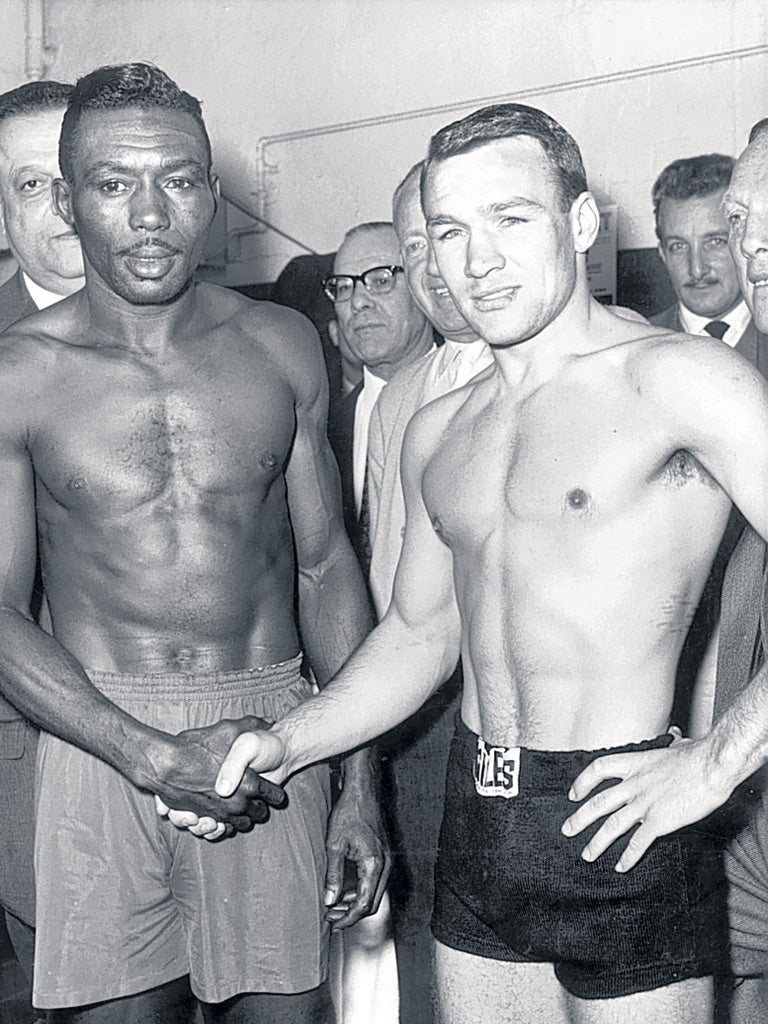

In 1959 Charnley went to Houston, Texas, to finally challenge for the world lightweight title, against Joe "Old Bones" Brown, a fighter who had lost his birth certificate and was probably, like a lot of good black fighters from the southern states at the time, a few years older than he claimed. It was a savage, short fight that ended with Charnley cut so badlyit was called off after five rounds.

"He needs a rest and I'm going to see that he gets it," Charnley's wife at the time said. Charnley was still only 24 but he had fought 40 times in five years and stocking the bank had taken its toll.

Boggis moved his fighter to theEuropean title, and a defence, and in April 1961 he worked with the promoter Jack Solomons to bring Brown, now nearly 35, to Earl's Court in London for a world title rematch. Just over 18,000 watched, thought to be an indoor record at the time, as Charnley appeared to win comfortably, perhaps by as much as five rounds.

However, an ancient and all- too familiar rift between Boggis and the referee Tommy Little meant Brown kept his title after 15 rounds. Boxing really was a tribal and savage business 50 years ago. "It was a disgrace," Duff never tired of saying. Boggis and Little had not spoken for years, their animosity open, and why he was allowed to sit in judgement on the fight is a dreadful mystery.

"I often wonder what would have happened if I had won that title," gentleman Charnley told me last year. "Perhaps I would not be the man I am now."

A few years later, in 1963, Duff and his partners brought Brown back to England for a non-title fight and Charnley stopped the relic in six rounds. "Joe was not the same fighter at that time," admitted Charnley, and arguably neither was the Dartford Bomber, as Charnley was known throughout his career.

Charnley finally retired after a trio of stunning fights in 1964, which perhaps perfectly capture both his brilliance and bravery and also just how different the modern sport of boxing brats is now compared to a time of real heroes. Charnley lost on points to the British welterweight champion, Brian Curvis, then beat the brilliant Kenny Lane, who had just lost over 15 rounds to Ortiz for the world title, and was finally stopped for the first time in his career when he was put in with Emile Griffith, who was the world welterweight champion. It was astounding matchmaking, even by the old standards of excess. Charnley retired after winning 48 of his 61 fights and with a fortune estimated at just under £500,000.

In retirement he ran hairdressersbefore moving into property deals that saw his wealth grow. He remained, however, an enigmatic and seldom-seen figure. In boxing circles, especially in London, he was always considered a legend and a sighting was rare and celebrated.

"The best fighter I met?" Charnley said to me after a short break when I spoke to him last year. "Kenny Lane. He was a gentleman." I would not be surprised if Lane said exactly the same thing.

David Charnley, boxer and businessman: born Dartford 10 October 1935; married firstly Ruth (marriage dissolved), secondly Maureen (two daughters); died 3 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks