Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau: Baritone hailed as the greatest lieder singer of the 20th century

In 1956 he sang with Peter Pears, who reported that he was 'very nice, and very musical, but very grand'

Nobody who was present at Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau's British debut will ever forget it. Thomas Beecham, who had a good nose for talent, had sniffed out a young German baritone who was making a name for himself. In England entirely unknown, he appeared on the posters as FISCHER DIESKOW. But he was a superb choice for Delius's A Mass of Life -– in looks somewhere between Tarzan and a Nietzchean übermensch; in voice, ideally sensuous and (as he later confirmed) entirely at home with Delius's idiom. The performance, on 7 June 1951, was a knock-out and next day at the Ritz, Beecham offered his discovery the role of Hans Sachs at Covent Garden. Fischer-Dieskau courteously, and wisely, declined, pointing out that at 27 such an assumption might be premature.

He was Berlin-born, to quite well-to-do parents, on 28 May 1925; his father, Albert Fischer, was a headmaster, apassionate promoter of concertsand an amateur composer; his mother was a von Dieskau. The family home echoed to music and to poetry, sothat conscription into a Hitler Jugend group was a brutalising experience which the young Dietrich found deeply uncongenial.

In January 1943 he sang Winterreise at his school, a performance interrupted for two hours by a heavy air-raid, and later that year he was conscripted into the army, eventually becoming a prisoner of the British in northern Italy, sometimes entertaining the allied troops with lieder and popular song recitals.

Repatriated in 1947, he stood in for an ailing baritone in Brahms' Requiem in Freiburg. The Bach Passions also came his way, but serious study was called for and he returned to Berlin to work with Hermann Weissenborn, his vocal mentor until his death in 1959. Success came quickly; during 1948 he made his stage debut (as Posa in Don Carlo) in Berlin, where he also broadcast Winterreise, while in Leipzig he gave his first solo recital.

The following year he began to appear at the Staats-opers of Vienna and Munich. In England he attracted the attention of two important impresarios – the formidable Walter Legge, of EMI, and Ian Hunter, then directing the Edinburgh Festival, where, in 1952, Fischer-Dieskau gave Winterreisewith Gerald Moore, who was bowled over by the exceptional gifts of "this young giant".

Returning to Edinburgh the following year, he appeared three times with Irmgard Seefried (who called him "Fi-Di") – once in Wolf's Italienisches Liederbuch, with Gerald Moore, and twice (on adjacent days before and after) in the Brahms Requiem. These performances were with the Vienna Philharmonic under Bruno Walter, who shared six concerts with Wilhelm Furtwängler. After the first I went round to congratulate all concerned. To my surprise,Fischer-Dieskau was not there; he had been seen leaving the hall. Going in search of him I discovered him sheltering rather miserably in the porch of a nearby church.

I assumed he had been dissatisfied with his own performance, so reassured him and coaxed him back to the hall. Only later did I learn that Furtwängler and Walter were to meet – in the greenroom that evening – for the first time since the war. On personal and political grounds the encounter was likely to be explosive. Fischer-Dieskau had not wanted to be present.

In Edinburgh, again, in 1957, he sang the "alto" part in Das Lied von der Erde – an arrangement for which I had discovered a precedent. In retrospect, it surprised me that both he and Otto Klemperer were willing to undertake this version, for it is not really satisfactory. Moreover, Klemperer was nervous (the Philharmonia had not played Das Lied before) and his baritone sometimes felt drowned. Nevertheless he brought a special, tender pathos to the last movement, the Dying "Ewigs" faultlessly enunciated, almost whispered. On this occasion – and on others – I tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade him to repeat the Delius.

He came to the Edinburgh Festival regularly and was immensely popular there, but his relationship with Aldeburgh was, for obvious reasons, morerewarding. Peter Pears had sung with him inGermany in 1956 and had reported that he was "very nice, and very musical, but grand". Later, Britten was to remark, "I'm scared of Dieter – he's the school bully." Notwithstanding these reservations, Britten was to write three works with his voice in mind: the Cantata Misericordium, the Songs and Proverbs of William Blake(premiered in 1965 with the composer accompanying) and – unforgettably – the War Requiem, first heard on 30 May 1962 and broadcast successfully despite Coventry Cathedral's obstructive staff and a spell of very cold weather. Fischer-Dieskau was deeply moved bythe occasion. At about the same time he proposed to Britten an opera onKing Lear, with himself in the titlerole and Pears as the Fool. Britten considered the project seriously but it did not materialise.

Not much of Fischer-Dieskau's work in opera was seen in Britain. Mostnotable was his Mandryka (Arabella) under Solti at Covent Garden in 1965: his aristocratic elegance suited the role perfectly. But Falstaff eluded him: rather too carefully sung, the disreputable old knight's boozy rascality was not within his histrionic range. And, truth to tell, he generally sounded less happy in Italian than in German roles, among the best of which were Wolfram and Amfortas (both at Bayreuth), Johnthe Baptist, Busoni's Faust, Wozzeck, both Olivier and the Count in Strauss's Capriccio and, eventually, HansSachs under Eugen Jochum in Berlin during the 1975-76 season. About his Mozart – the Count, Don Giovanni, Don Alfonso, Papageno – there were conflicting views.

Reservations were also sometimes expressed about his singing of lieder. While the sheer beauty of his voice – dark chocolate in colour – his immaculate technique, his crystal diction, his intelligence and his seriousness were unarguable, there were those who found excessive what Suvi Grubb (who recorded, for EMI, innumerable lieder with him) called his "enormous dynamic range" and Walter Legge his "Prussian exaggeration of consonants". But the total of his recorded achievement was awe-inspiring: most of Schubert (including Die schöne Mullerin, surely a cycle for tenor voice), Wolf, Schumann; much of Brahms, Beethoven and Mahler; some of Mendelssohn and Liszt; all of Strauss.

His regular accompanist was Gerald Moore, whose retirement recital in 1967 he took part in with Victoria de losAngeles and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf,a frequent partner in Wolf; but he also collaborated with Barenboim, Brendel, Richter, Sawallisch and once, disastrously, with Horowitz. To mark his70th birthday, Deutsche Grammophon issued a bumper collection of 44CDs, mostly with Moore, but among them some memorable Wolf and Brahms with Barenboim.

Fischer-Dieskau's repertoire outside lieder and opera was by no meansconventional. Though its notorious first night was aborted, he would have sung in Henze's The Raft of the Medusa;he did sing Blacher's radio opera, The Flood, several works by von Einem and by Reimann, and Lutoslawski's LesEspaces du Sommeil, which waswritten for him. As his vocal powers waned he took up conducting and generous conductor-colleagues loaned him their orchestras. But, though his conception of the music was often admirable, his technique was only "just about adequate", according to Suvi Grubb, for whom he recorded Schubert's 5th and 8th symphonies, a disc which sold poorly.

He was four times married. His first wife, the 'cellist Irmgard Poppen, died giving birth to their third son. His second and third marriages were unsuccessful. But his last, to the soprano, Julia Varady, brought him great happiness. Together, in 1984, they performed Bartok's Duke Bluebeard's Castle at the Edinburgh Festival, where he also gave his last recital there, a Brahms programme with Hartmut Höll. Five years later he published his memoirs, Echoes of a Lifetime.

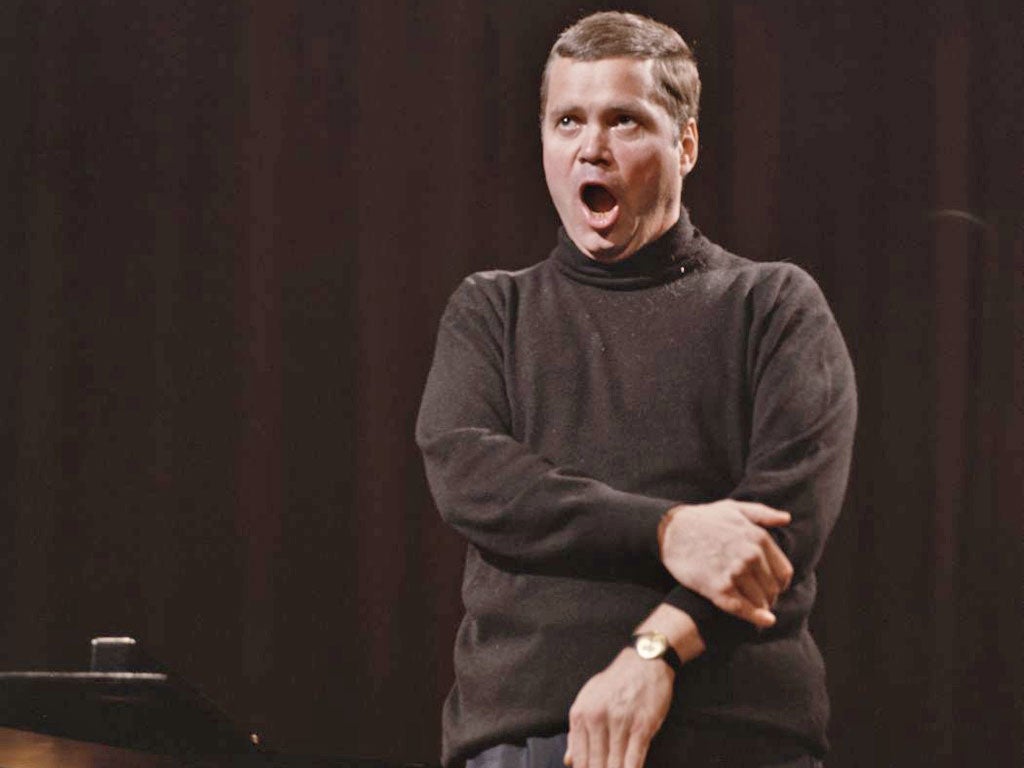

On the concert platform, Fischer-Dieskau was imposing. Always immaculate, his posture was elegant, attentive; he was self-evidently listening. He was invariably generous in acknowledging his accompanist. Whether singing Bach, with inspired simplicity, or Strauss (or, for that matter, Delius) with extrovert passion, his overall mastery was such that every performance was an "event" and – as a consequence – the lieder recital became, in the post-war years, a popular manifestation. And surely, his mannerisms notwithstanding, no other baritone delivered a more beautiful sound with such intelligence and intensity.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone: born Berlin 28 May 1925; married 1949 Irmgard Poppen (died 1963; three sons), 1965 Ruth Leuwerik (divorced 1967), 1968 Christina Pugel-Schule (divorced 1975), 1977 Julia Varady; died 18 May 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments