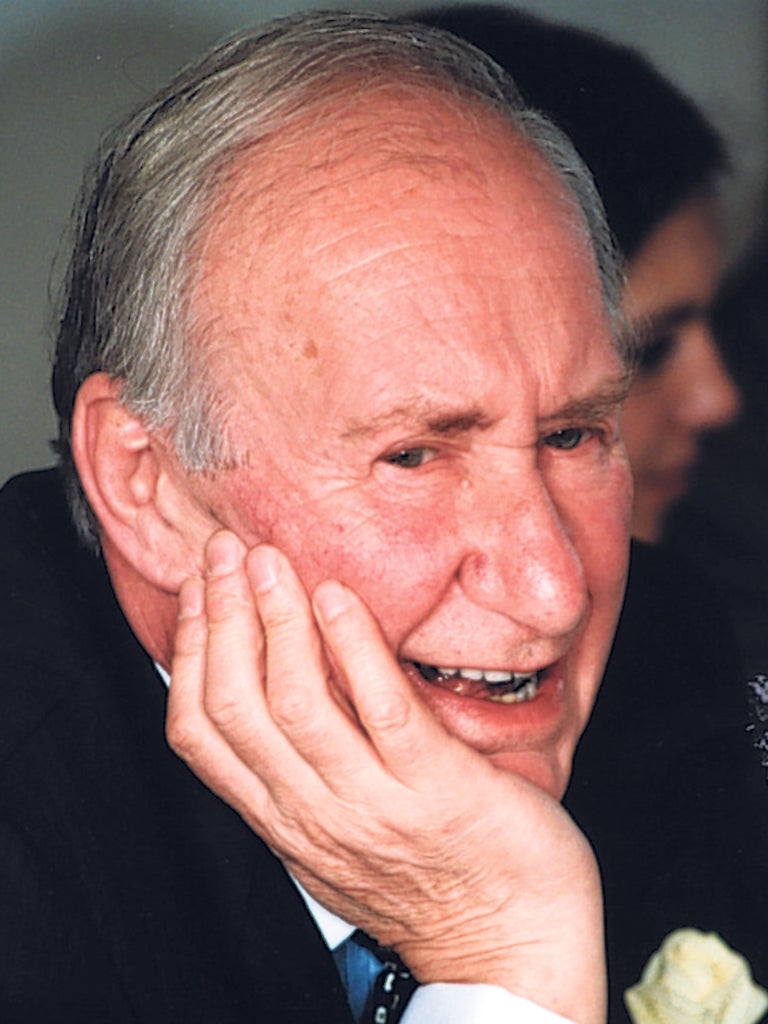

Doctor Eric Brenman: Highly regarded psychoanalyst

Eric Brenman was a psychoanalyst and former President and Training Psychoanalyst of the Institute of Psychoanalysis. He made a distinctive and important contribution to psychoanalysis within the post-Kleinian tradition, and his collected papers on psychoanalytic theory and technique can be found in his seminal book The Recovery of the Lost Good Object (2006, Routledge: London).

Brought up in North London, Brenman trained as a doctor then as a psychiatrist. His psychoanalyst during his training was Hanna Segal, and one main strand of his work developed her ideas on reparation. In a 1952 paper on creativity, Segal had put the issue thus: "It is when the world within us is destroyed, when it is dead and loveless, when our loved ones are in fragments, and we ourselves in helpless despair – it is then that we must re-create our world anew, reassemble the pieces, infuse life into dead fragments, re-create life".

Brenman's focus was on difficulties patients experience with this task of repair, a task central to life. The main thrust of his work may be summarised as a detailed theoretical and technical psychoanalytic study of the struggles of patient and analyst to reassemble fragmented inner loved ones.

I was privileged to go to Brenman for supervision. He had a brilliant way of finding potent images to help understand underlying difficulties patients may face. He once illuminated a particular patient's current plight with the tale of the Flying Dutchman in Wagner's opera. The Flying Dutchman is an example of the archetypal legend of man condemned endlessly to wander alone and tormented by guilt about his greed, corruption and destructiveness, unable to find inner rest, forgiveness and love.

In Wagner's version he can only be saved by the love of a good woman, personified by Senta. However, full of doubt and suspicion, and unable to trust in Senta's abiding love and faithfulness, the Dutchman destroys himself. Brenman's point was that we need a good loving relationship in order to bear knowing about our own destructiveness, but the good relationship we need may be very difficult – sometimes too difficult – to bear and to believe in.

He thought that what helps patients over time is having the sense that their psychoanalyst really appreciates what it feels like for them to be who they are. He conveyed a sense that, if the analyst were in the same situation with the same pressures the patient had and has, would he or she do any better than the patient? He invited one to realise: probably not. He conveyed an analytic stance with a deep sense of "there but for the grace of God would I have gone or be".

In a celebrated paper, Cruelty and Narrow-mindedness (1985) he discussed those who consume and possess without a conscious sense of guilt or responsibility. He emphasised the narrow-mindedness of this view of the world and its intimate connections with cruelty. The person expects ideal provision and is driven to punish people for not being ideal and for not being able to satisfy him or her in every way.

Brenman's paper was important in that it helped open up a path to the better psychoanalytic understanding of grievance-based states of mind and to further work in this area. He brilliantly discussed the quality of narrow-mindedness, its ruthless greed, its persistence and its blinkered focus, one that can occlude the benign influence of ordinary love and understanding. These ideas have relevance for society at large. Brenman argued that this syndrome could be observed in wealth-seeking, wars, sexual conquests, racism, political beliefs, religious corruption, – often fuelled by a crusade of holy grievances.

In his paper Matters of life and death – real and assumed (2006), he wrote of the complex conflictual relations between the parts of the self that embrace life and truth and those that embrace deadliness, lies and corruption. He stressed that compromises are necessarily reached. For instance, he argued that people may kill off or deaden parts of themselves that are capable of love, not out of pure destructiveness but in order to avoid being excessively tormented by guilt, a useful perspective on these situations which can be so difficult in psychoanalysis. What matters then is not that we kill off but how much we kill off.

Brenman's psychoanalyst-as-guide comes across with modesty of aim and awareness of limitation and context, whose needed strength to withstand the patient's and his or her own omnipotence is like a bough that bends rather than one that breaks under pressure. This is the strength "to bear knowing and experiencing, and knowing how much one can bear''.

He had a dry, ironic, sometimes cheeky sense of humour. He was a deeply cultured man with a penetrating interest in whatever his attention focused on. He lived life to the full: he loved good food, wine, music,theatre, books and football, and he loved Italy. He said his favourite play was The Bacchae by Euripides, which he once cited as an illustration of just how badly things can go wrong if we disrespect or discount the reality that we are cursed with an omnipotent, god-like part of ourselves.

Eric Brenman, psychoanalyst and medical doctor: born London 12 January 1920; married firstly Ishbel McWhirter (marriage dissolved; two sons), secondly Irma Pick (one stepson); died 6 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks