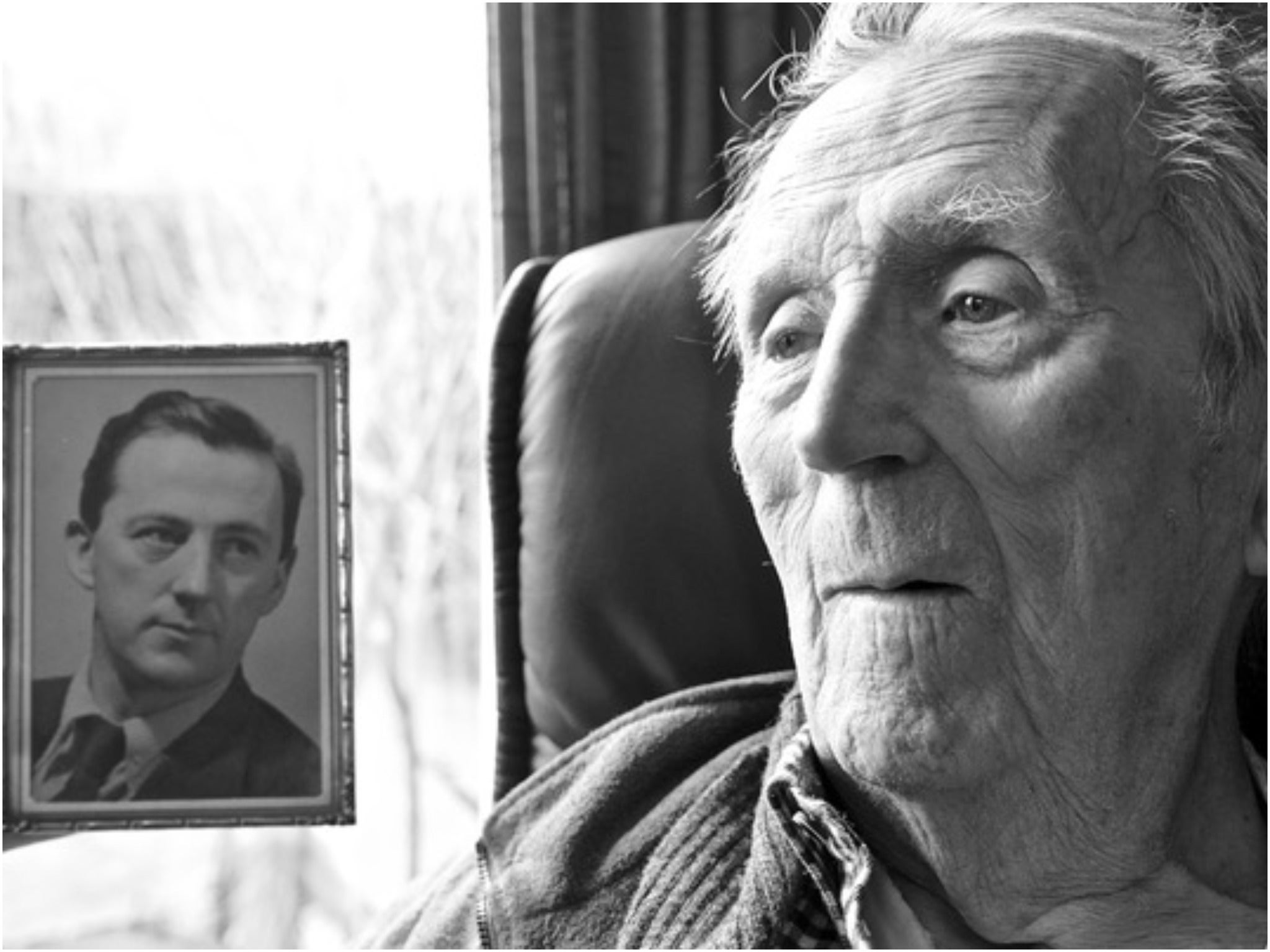

Emyr Humphreys: One of the most courageous novelists of post-war Wales

The award-winning author published more than 20 works in which he wrestled with questions about human progress and morality

One of the most prolific and distinguished novelists of post-war Wales, Emyr Humphreys was primarily concerned with the moral questioning associated with the Protestant conscience, examining in particular the means by which good is, or is not, transmitted from one generation to the next.

Unable to accept the novel as mere entertainment, he believed that, in our time, the novelist’s attitude is more crucial than his manner of expression. His Christian faith led him to conclude that, despite all evidence to the contrary, human progress is possible, however slow, towards the kingdom of God. This was no facile conclusion but one worked out, often at great personal cost, in a long life devoted to pacifism, Welsh nationalism, cultural analysis, and his work as a writer.

He published, besides several collections of poetry and short stories, more than 20 novels in which he wrestled with such questions as whether it is love that makes human progress possible, whether conscience is handed down from parents to children or learnt from contemporaries and the experience of living, and whether, in such a complex process, it is reasonable to presume divine intervention.

From about 1951, the year in which his third book, A Change of Heart, appeared, he was engaged in writing the Protestant novel in which his deep sympathy for individuals, particularly the dissident whom he saw as the key figure of our time, was subsumed in concern for the future of civilised society, which for him meant, in the first instance, the continuance of Wales and the Welsh language.

Humphreys, who has died at the age of 101, worked hard to achieve his vision of a Wales emerging at last from the ravages and betrayals of the past 200 years, and made it the central theme of his writing. He was born in Prestatyn, a seaside resort in the old county of Flintshire, and brought up as English-speaking at nearby Trelawnyd (formerly called Newmarket). At the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, he read history, came into contact with Welsh-speaking contemporaries with literary ambitions, learnt Welsh and joined Plaid Cymru.

His politics were drawn from the work and example of Saunders Lewis, the playwright and father of modern Welsh nationalism, whom he revered as a necessary figure and whose plays he was later to translate and produce for television. He also shared some of the views of RS Thomas, although in his sympathy with nonconformist, egalitarian Wales he was very different from both Thomas, an Anglican, and the Catholic Lewis.

Liable for military service in 1940 after only two years at university, he declared himself a conscientious objector on Christian pacifist grounds and was sent to work on the land in Pembrokeshire. Four years later, still subject to call-up, he went as a war relief worker first to the Middle East and then to Italy, where he was an official of the Save the Children Fund under the aegis of the UN; he also helped to run a refugee camp in Florence.

His marriage, on his return to Wales in 1946, was crucial to his development as a writer. Raised as a Christian in Wales, and as a young man intended for the Anglican priesthood, he married Elinor Jones, the Welsh-speaking daughter of an independent (congregationalist) minister, and so discovered the continuity of the religious and politically radical culture that he was to make the stuff of his novels. Success followed soon afterwards: with his fourth novel, Hear and Forgive, published in 1952, he won the Somerset Maugham Award and with his seventh, A Toy Epic (1958), the Hawthornden Prize.

After two years of teaching at Wimbledon Technical College in London and four at Pwllheli Grammar School, Humphreys joined the BBC in Cardiff as a drama producer, only to find that radio and television took a heavy toll on his creative energy. He left in 1965 to take up a lectureship in drama at the University College of North Wales, Bangor.

In that year he published Outside the House of Baal, his ninth and, in the view of many, his finest novel. The longest of all his books concerned with the transmission of good, it is a portrait of the Reverend JT Miles, a Calvinistic Methodist minister, who is selfless, warm-hearted, pacific, inarticulate – but also, in his personal relationships, inadequate, sometimes foolish and, at the last, bewildered and overwhelmed by an alien world. This powerful novel is about family ties, friendship and trust; more profoundly, it is about agape, again betrayed by eros and found wanting because it is too quick to abandon tradition and too slow for the vulgarities of modem society.

Humphreys left academic life in 1972 to give his time entirely to writing, though he still depended for his income on making programmes for television, often with his sons Sion and Dewi. Over the next 20 years from his home on Anglesey, he produced a septet of novels collectively entitled The Land of the Living on which his reputation is sure to rest secure.

The first to appear was National Winner (1971); it was followed by Flesh and Blood (1974), The Best of Friends (1978), Salt of the Earth (1985), An Absolute Hero (1986), Open Secrets (1988), and Bonds of Attachment (1991). The central character of this roman-fleuve is Amy Parry, the working-class schoolteacher who becomes Lady Brangor, and her climb to social eminence and eventual descent into spiritual poverty are meticulously charted. Her once-radiant patriotic idealism is gradually compromised as she embraces the self-serving, hypocritical standards of the Labour Party establishment. These books teem with lesser, but more sympathetic characters, and take in much of the history of Wales and Europe in the 20th century, from the economic depression of the inter-war years to the more affluent, but equally challenging conditions of our own post-industrial times.

Many readers have enjoyed Humphreys’s novels, particularly the lyrical quality of his early books, the surface wit of his characters’ dialogue and the comedy of his plots, without always understanding their deeper concerns. Others have been put off by the later novels’ extended time-sequences, the complicated narrative patterns, the episodic cutting, the author’s lack of sentimentality towards his characters, the sometimes impenetrable schemas, the high seriousness of his preoccupations, and by the very fact that, in the case of the septet, the novels were not even published in chronological order. Almost always, the reader is left to draw their own conclusions because the author has refused to play the role of the omniscient, ubiquitous narrator.

In England, particularly, Humphreys generated less excitement among critics and readers after his early triumphs, despite the interest of his London publishers, perhaps on account of his unrelenting search for a contemporary morality or because, more superficially, the Wales portrayed in his novels had no place for the stereotypes that the English-speaking world has come to expect from Welsh writers. His characters, for instance, speak a standard English rather than the “look you, boyo” idiom of popular caricature.

The same literary qualities are to be found in the rest of Humphreys’s work: a collection of stories entitled Natives (1968), four volumes of poems (some of which appeared in the Penguin Modern Poets series in 1979), and his selected history of Wales, The Taliesin Tradition (1983), which is important for a full understanding of the themes in his novels. Shards of Light, a collection of previously unpublished poems, was published to mark his 100th birthday.

Humphreys’s unswerving devotion to the Welsh language led him to give active support for Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (the Welsh Language Society), whose militancy, perseverance and non-violent methods he greatly admired. On one occasion, in 1973, that devotion also resulted in a spell in prison, after he refused to pay the BBC a licence fee, as part of a campaign for a Welsh language television service that led to the establishment of S4C in 1982.

In his disapproval of the English presence in Wales, he was implacable and thoroughgoing: for example, he insisted on considering himself a Welsh, rather than an Anglo-Welsh writer, and chose to belong to the Welsh-language section of the Welsh Academy, the national society of writers. This was not perversity on his part but a declaration of his Welsh identity, which, once achieved, was something to be cherished as life itself.

His private manner revealed the milder man whom I knew and admired, while his modesty and keen interest in the work of others won him many friends among a younger generation who recognised in him a Welsh patriot of great courage and staunch conviction, and a writer of wide horizons and immense literary gifts.

Emyr Owen Humphreys, novelist, born 15 April 1919, died 30 September 2020

Meic Stephens died in 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks