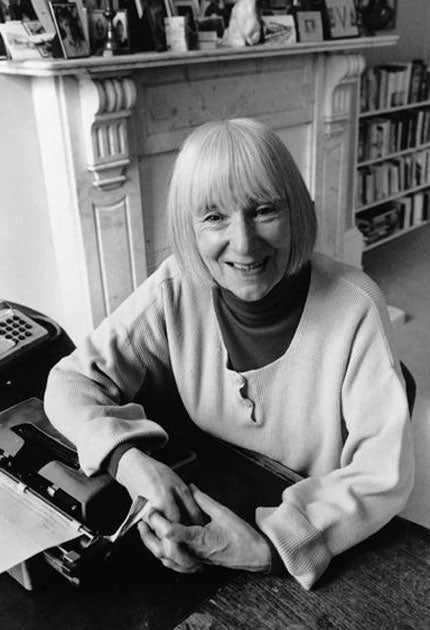

Eva Ibbotson: Novelist who moved from adult romance to writing entrancing fantasies for children

The author for most of her working life of worldly adult love stories and irreverent fantasies for children, Eva Ibbotson came to late fame at the age of 76 with the publication in 2001 of her stirring Amazonian adventure story Journey to the River Sea. Written as a full-blooded romance for young readers, this new departure sold more than 200,000 copies and won the Smarties Prize Gold Medal. All the more remarkably, she was suffering at this time from lupus, a cruelly debilitating disease in which the body's immune system turns on itself. Often exhausted after only a few hours, and with fingers so stiff that it was sometimes hard to hold a pen, she continued to write in this dramatic vein for children with new verve and unslaked powers of invention. Ironic and uncomplaining to the last, she leaves a legacy of fine writing as highly individualistic as she was herself.

Ibbotson's childhood was as turbulent as anything in her stories. Born in 1925, she came to Britain in 1933 from Vienna without a word of English. She was accompanied by a governess and her Jewish father Berthold Wiesner, a brilliant physiologist who had been offered a job at Edinburgh University. A pioneer of human artificial insemination, he used sometimes to draw on his own resources when volunteer donors – according to Eva, largely consisting of "various clergymen from Gloucester" – were not, as it were, on hand. "Only recently I met a half-sister for the first time," she told me once. "She was eager to hear any details about my father, whom she had been able to trace following a DNA test performed first on her, then on me."

Eva's adored mother Anne Gmeyner arrived in Britain a year later. A charismatic and beautiful communist playwright, also Jewish, she had worked with Brecht and written film scripts for Pabst. Long separated from her husband, she was living with an aristocratic Russian philosopher in Belsize Park, north London. Eva would travel between the households, each occupied by glamorous and sophisticated parents prone to criticise the other in her presence. Attempting to ingratiate herself wherever she was, changing her hairstyle and clothes in the train from one party to another, it was with some relief that she finally enlisted as a boarder at Dartington Hall, the famous co-educational Progressive School set in deepest Devon.

Greeting its determinedly informal headmaster WB Currie with a full curtsey on their first meeting, Eva soon realised that in her embroidered Austrian dress and white ankle socks she stood out from the other universally dressed-down pupils. But the school's friendly atmosphere was exactly what she was looking for. Remembering her time there with great affection, she recreated the whole school, with its occasionally wacky ideas, in her 1997 adult story A Song for Summer.

Back in Belsize Park,Eva's mother wrote her best-known novel Manya in 1938. Her father had become interested in the maternal behaviour of rats, which as Eva pointed out, he found "more satisfactory than the maternal behaviour of my mother". Writing a classic monograph on the subject, he later turned his attention to ESP, working with the Cambridge psychologist RH Thouless. In emulation of her father, and influenced by Dartington's inspired biology teacher David Lack, better known as the author of The Life of the Robin, Eva decided to study physiology at Bedford College, London. Getting a good degree without ever really taking to her subject, she moved on to do research at Cambridge. There that she met and married Alan Ibbotson, an academic entomologist.

Joyfully abandoning her uncompleted PhD, she set up house with her new husband in Newcastle while he taught at its university. Four children followed in a marriage lasting 49 years which was only brought to an end by Alan's death from a heart attack in 1998. Ibbotson started writing early on, producing love stories for various magazines including The Lady and Good Housekeeping. Once her youngest son started school she turned to novels.

Her first of eight romances for adult readers, A Countess Below Stairs (1981) tells the story of a Russian noblewoman forced to work as a housemaid to an English Earl engaged to a beautiful heiress with alarming views on eugenics. Stocked with memorable minor characters, the story culminates in a serenely happy ending. This was a pattern Eva maintained, putting this preference down to her own often unfulfilled need as a child to feel securely valued and loved. But her fiction gave her ample opportunity "to reassure people and reassure myself. I want my characters to find love and safety."

Magic Flutes (1982) also features an impoverished émigré aristocrat, young Princess at the Hapsburg court toiling in a menial capacity for an anarchic opera company. Music features, too, in The Morning Gift (1993) set again in pre-war Austria. Passionate, clever Ruth Berger falls in love with Heini Radek, a prodigy studying the piano at the Vienna Conservatoire. Wide-ranging and often amusing, these and her other novels set in the mid-Europe of her youth were written primarily to give both herself and her readers all the pleasures of intelligent escapism.

Well received in Germany and America, they experienced in Britain the critical neglect suffered by numbers of other high-class romantic writers. Eva's early writing for children was in a different vein. A succession of what she described as "rompy" stories started with The Great Ghost Rescue (1975), which established her as a satirical force in pre-adolescent fiction. This was followed by Which Witch? (1979, runner-up for that year's Carnegie Award). It tells the tale of a proud wizard who decides he must marry in order to produce an heir. Organising a contest to discover which witch to choose for his bride, he is finally nabbed by beautiful Belladonna after she manages to survive a number of set-backs.

More mostly jolly witches appear in further stories, often based on a compound of Eva's grandmother, aunts and older cousins, many of whom also came to Britain in the late 1930s. As she recalled, "The din they used to make when they were together, the strange clothes they wore, the small moustaches some of the older ladies had and the impression they all gave of perpetually wandering about with no true home to go to made a big impression on me as a child. I was very fond of them, which is why my witch characters, although sometimes mischievous, are always basically kind." But one particular harpy with an unflattering hairstyle and ostentatious handbag is taken directly from Mrs Thatcher, a politician Eva neither liked nor respected.

The Secret of Platform 13 (1994) was also successful. Its vision of a hidden entrance at King's Cross Station leading to another world inhabited by ghosts and wizards open for nine days every nine years, anticipated in its rich comic inventiveness JK Rowling's Harry Potter stories, the first of which followed three years later. But after the death of her husband, Eva turned away from purely light-hearted children's fiction. In her Journey to the River Sea (2001), emotions formerly kept at arm's length by a series of jokes were now allowed full expression.

In a Cinderella plot aimed at older children, a wronged orphan named Maia living at the turn of the last century finds happiness after suffering at the hands of cruel guardians. It was set in South America, a country Eva had never visited, the research that went into its vivid evocations of natural history a tribute to her late husband. As she put it, "Writing about some of the things he enjoyed was one way of keeping his presence close to me when he was no longer there."

The book was later successfully adapted for the stage. It was followed by The Star of Kazan (2004), set again in Hapsburg Austria and involving another orphan child and an evil impostor-mother. Eva's tenth novel for children, The Beasts of Clawstone Castle (2005) was a return to the jokey ghost stories. Her last novel, The Ogre of Oglefort, about an ogre having a nervous breakdown, was short-listed for this year's Guardian Children's Fiction Prize

Living in a pretty terraced house in a Victorian suburb of Newcastle, crammed with painting and photographs and with a papier-mâché brick on the mantelpiece made by her grandchildren and labelled "writer's block", Eva cut a defiantly cosmopolitan figure; a visit ensured a feast of racy conversation laced with salty language. Her Christmas card for 2005 reproduced a photograph showing her being carried piggy-back by her "noble stepbrother" during a visit that previous summer to Egypt's Valley of the Kings. It was typical of the resolute, feisty spirit that drove her right to the end.

Maria Charlotte Michelle Wiesner (Eva Ibbotson), novelist: born Vienna 25 January 1925; married 1949 Alan Ibbotson (three sons, one daughter; died 1998); died 20 October 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments