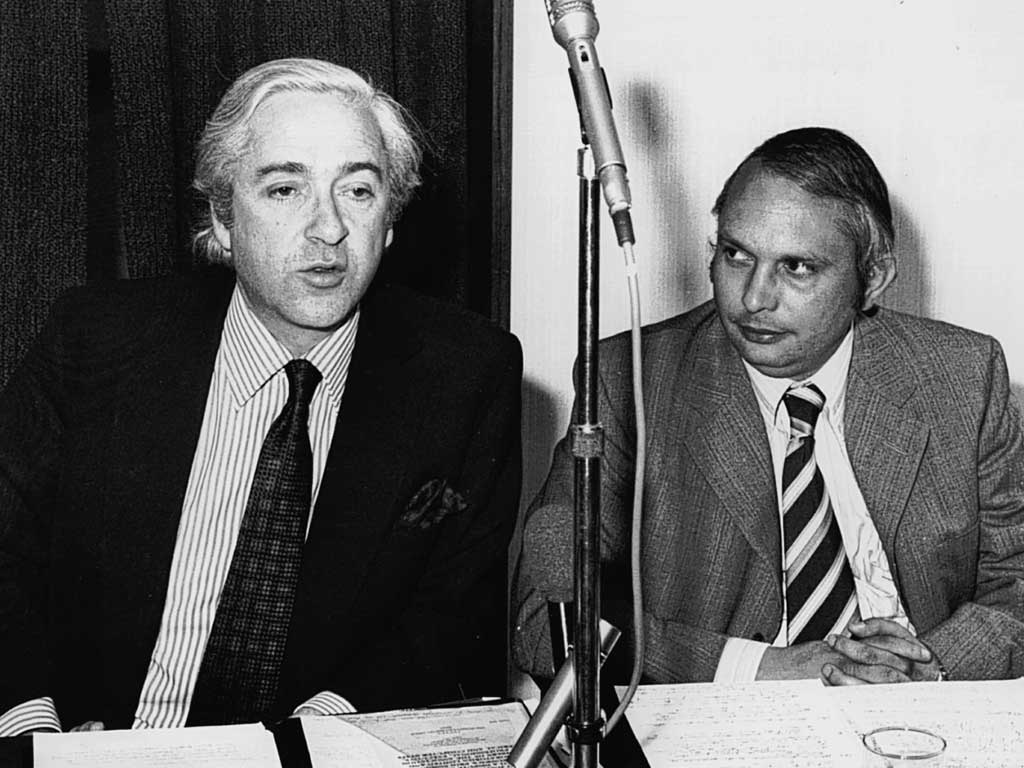

George Ward: Grunwick owner whose strike battle set the scene for Thatcher's union reforms

As boss of a North London photographic company in the mid-1970s George Ward played a central role in a key episode in Margaret Thatcher's developing belief that the power of Britain's trade unions had to be curbed. The strike at his firm dragged on for two long and bitter years, encompassing violence on the picket lines, huge political controversy and high-level legal proceedings before ending in defeat for the unions.

Ward had the strong support of Thatcher, then Leader of the Opposition, who hailed him as a champion of freedom in the dispute at his Grunwick film processing laboratories. He refused to yield in the long-running trial of strength with the workers, eventually prevailing and helping confirm Thatcher in her belief that union power could be broken.

The episode hugely embarrassed the Callaghan Labour government. There was an amount of public sympathy for the strikers, many of whom were Asian women who became known as "strikers in saris". But it was another matter when nightly television reports showed ugly clashes between thousands of pickets, who included miners bussed in by Arthur Scargill, and riot police in paramilitary gear. There were more than 500 arrests and many injuries "when policemen's helmets started flying", as a reporter at the time put it.

Callaghan hurriedly sought a way out, commissioning a senior judge, Lord Scarman, to produce a report, but legal proceedings dragged on before the strikers eventually gave up the fight. Ward declared he was standing up for the right to work and the importance of freedom. He insisted that he was not anti-union – but he also insisted that "the dominant factors behind this dispute are Marxist-inspired."

George Ward was born into an Anglo-Indian family in New Delhi in 1933. The son of a well-off accountant, he was fascinated by horse racing all his life, and had youthful ambitions of becoming a jockey. But the family fell on hard times after his father's death and, almost penniless, moved to England.

Ward worked as a postboy before winning a scholarship to a London polytechnic, where he qualified as an accountant. He spent three years in Rio de Janeiro before returning to become a partner in an accountancy firm.

He and two business associates founded Grunwick Laboratories at a time when developing holiday snaps was big business. He was particularly proprietorial about the firm, having invested his savings in it and working long hours to build it up.

In 1976 a male worker was sacked on the grounds that he was working too slowly. Other workers protested, joining the trade union Apex, and when around 150 went on strike all were sacked. Picketing began and the two-year dispute was under way.

Conditions in the plant were said to be harsh, though Scarman's report did not bear out allegations that it was essentially a sweatshop. Ward contested accusations that he exploited immigrant labour, declaring: "I myself am an immigrant." He lauded those employees who remained at work, saying they had "heroically withstood the bully-boy tactics of the extremists."

Some Labour ministers and MPs supported the strikers while Conservatives were divided among moderates who favoured a compromise solution and others who saw it as an important trial of wills. Keith Joseph, who became a leading Thatcherite, called it "a make-or-break point for British democracy", saying that unless the unions lost, Grunwick would represent "all our tomorrows". The left-wing journalist Paul Foot concurred, describing the dispute as "a central battleground between the classes and between the parties".

Those who continued to work were ferried in coaches fitted with grilles to ward off the milk bottles and other missiles. Pickets were also bussed to the site, which the media called "the Ascot of the left". Some postal workers refused to handle Grunwick mail. Merlyn Rees, the Home Secretary, was barracked by crowds of angry pickets when he went to the site to insist that the heavy police presence was necessary.

The Trades Union Congress, which initially supported the strike, grewuncomfortable with the clashes and displays of militancy, which it reckoned had got out of hand and was costing the movement support. The TUC general secretary, Len Murray, would latersay: "There were calls for us to blacklist Grunwick's post forever, to drive the company out of business, and even turn off Mr Ward's gas, water and electricity - all very illegal and very unacceptable to the majority of moderate British people."

Legal proceedings dragged on, with Ward winning some battles and losing others, until eventually the House of Lords upheld his right not to recognise the union. Support then drained away.

The Grunwick company prospered and expanded after the strike, though the rapid developments in modernphotographic technology, particularly in digital cameras, eventually hadan effect and it closed in 2011. Wardran into trouble with the Conservatives in 1988 when the Hendon branch,which he chaired, was suspended by the Party. He denied allegations that he had signed up relatives and employees as members in advance of an important meeting.

He was a prominent sponsor of horse racing, with a number of major races bearing the names of his various companies, but he felt he was denied access to the establishment. On his death Edward Gillespie, managing director at Cheltenham race course, said: "George was a great man but unfortunately he never quite achieved what he wanted to in racing because he was never allowed into the inner chambers, and that was a big disappointment to him.

"George was only allowed to get so far because of who he was, because of his background, his relationship with government, his disappointment with Margaret Thatcher. The ranks sometimes closed against him, and it was very sad."

George Ward, businessman: born New Delhi, India 2 April 1933; married 1965 Loretto Hanley (one son, one daughter); died 23 April 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks