Geraldine Ferraro: Lawyer who made history as first woman vice-presidential candidate for a major US party

Geraldine Ferraro was buried beneath one of the great landslide defeats of American politics. But her place in US history is secure, as the first female (and moreover the first Italian-American) candidate for president or vice-president for one of the country's two major political parties.

Since that landmark election of 1984, women have broken through many barriers. Their numbers in both Senate and House have soared, while three women have served as Secretary of State and one of them – Hillary Clinton – came close to securing the Democratic nomination in her own right. Between 2007 and 2011, Nancy Pelosi held office as the first woman Speaker, and in 2008 another woman, Sarah Palin had a place on a national ticket. But Ferraro was the trailblazer.

At the time, the circumstances were certainly propitious, even though she was a mere third-term Congresswoman from New York, of scant national reputation. Much was then being made of the "gender gap" in US politics, whereby women voted in much larger numbers for Democrats. At the same time Walter Mondale, the party's White House nominee, was a worthy but somewhat dull figure, desperate to shake up a contest in which the popular incumbent Ronald Reagan, helped by a surging economy, was universal favourite to win a second term. Many therefore argued, why not choose a woman?

For weeks, the name of Geraldine Ferraro had been high on the possibles list, but it was none the less a sensation when Mondale announced her selection on 12 July 1984. Such was the throng of reporters that police had to rope off her office on Capitol Hill. The frenzy prefigured the one that would surround Palin 24 years later, when she was plucked from even greater obscurity by John McCain.

For many women, the moment when Ferraro accepted her nomination at the Democratic convention in San Francisco, was not just a political, but a societal, breakthrough. "My name is Geraldine Ferraro," she began, amid chants of "Gerr-ee, Gerr-ee", from what seemed to be an audience exclusively of women. "I stand before you to proclaim tonight, America is the land where dreams can come true for all of us." Not a single soul in the convention arena, or in front of a TV at home, missed the emphasis on the word "all".

But even if Geraldine Ferraro had not been a woman, her ascent would have been remarkable. She was the only daughter of Dominick Ferraro, an Italian immigrant who ran a restaurant in the Hudson river town of Newburgh, 60 miles north of New York. Two of her three brothers died before she was born, and she lost her father when she was eight. The family finances were stretched thin, but there was just enough money to put Geraldine through school and university, where she shone. "She delights in the unexpected," her college yearbook noted prophetically.

By day she was a teacher, by night she studied law at Fordham Law School in New York City, one of only two women in a class of 179. In July 1960 she graduated and two days later married the John Zaccaro, a real estate businessman. For the next 13 years, Ferraro played the traditional role of the Italian-American mother, devoting herself to home and raising the couple's three children. But in 1974 she took up law full-time, as as an assistant district attorney in Queens, specialising in family violence and rape.

Before, she had barely dabbled in local politics, but the cases she dealt with hardened her Democratic and liberal convictions. When the Congressman representing Queens announced his retirement, Ferraro seized the opportunity with both hands, and in November 1978, she was elected to Congress for New York's 9th district. "Finally, a tough Democrat," was her slogan, referring to her law-and-order background. After seeing off two rivals in the primary, she defeated her Republican general election opponent by 10 points.

In Washington her approachable, breezy style soon impressed the Democratic powers-that-be. By 1980, Ferraro was a co-chair of the Carter-Mondale campaign, before being twice re-elected to Capitol Hill, in 1982 with 73 per cent of the vote. As talk grew of a woman on the Party's 1984 presidential ticket, she was an obvious option.

For a moment in the giddy aftermath of Mondale's announcement, the Democratic pairing drew level in the polls with the Reagan/George HW Bush tandem. But reality – and wounding financial rumour – quickly took over.

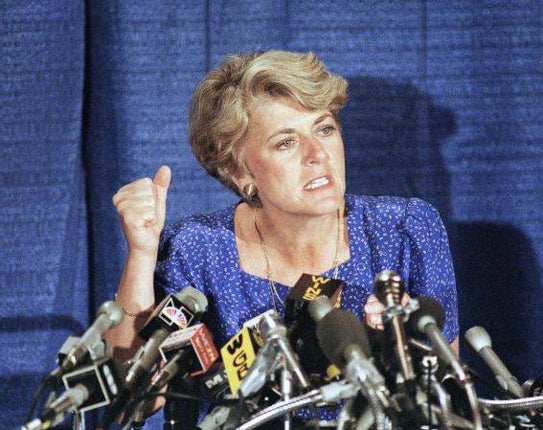

From the outset, the media concentrated on Ferraro's gender. Could a woman be tough enough to face down the Russians, she was asked – what did she know about nuclear weapons? In short order, though, an even trickier problem emerged, with questions about her husband's financial dealings, even insinuations that he was connected to the mafia.

The controversy was a godsend for the Republicans, who could assail a female candidate without being accused of sexism. Nor did Ferraro help her cause, when she was asked why her husband initially refused to make his tax return public. "You people who are married to Italian men, you now what it's like," she quipped, intensifying public curiosity and attracting charges of ethnic stereotyping for good measure.

Eventually the controversy abated, and Ferraro made partial amends with a solid debate performance against Bush, at one point lambasting his "patronising attitude that you have to teach me about foreign policy" – a subject on which she had in fact amassed considerable expertise during her six years on Capitol Hill. Barbara Bush earned her a little extra sympathy too, by describing her husband's opponent as "that four-million-dollar – I can't say it, but it rhymes with 'rich'."

By then, though, the election was already lost. On 6 November 1984, Reagan carried 49 of the 50 states, winning by 18 percentage points. Even women in their majority went for the Republican. Analyses afterwards concluded that Ferraro had neither helped nor hurt her party's chances.

Her political career never recovered. She was in much demand as a speaker and published a best selling memoir, Ferraro: My Story. But John Zaccaro was charged with financial offences and their son John Jr was jailed for four months for cocaine possession. Her husband would be acquitted, but the uncertainty forced Ferraro to pass up a 1986 Senate race she might well have won.

In 1992 she again tried and failed, brought down by more allegations of financial chicanery. After a brief return to the law, she was named by the newly elected Democratic president Bill Clinton as US ambassador to the United Nations Commission for Human Rights, a post in which she was highly effective. In 1996, her public profile grew further, with a successful stint as the liberal host on CNN's Crossfire programme.

Once again a Senate bid in New York beckoned, but she lost the 1998 primary to choose a Democratic candidate to unseat the Republican incumbent Al D'Amato. This time the campaign did not get personal; Ferraro was simply outspent and outmanoeuvred by her opponent Chuck Schumer, who went on to rout D'Amato in the general election. It was her last campaign.

But Ferraro had no regrets. "I was constantly being asked, 'Was it worth it?' Of course it was worth it!" she wrote in her 1998 memoir Framing a Life, A Family Memoir. "My candidacy was a benchmark moment for women. No matter what anyone thought of me personally, or of the Mondale-Ferraro ticket, my candidacy had flung open the last door barring equality – and that door led straight to the Oval Office."

Geraldine Anne Ferraro, lawyer, politician and broadcaster: born Newburgh, New York 26 August 1935; US Representative for New York, 9th Congressional district 1979-1985; Democratic candidate for vice-president 1984; US ambassador to United Nations Commission for Human Rights 1993-1996; married 1960 John Zaccaro (two daughters, one son); died Boston, Massachusetts 26 March 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments