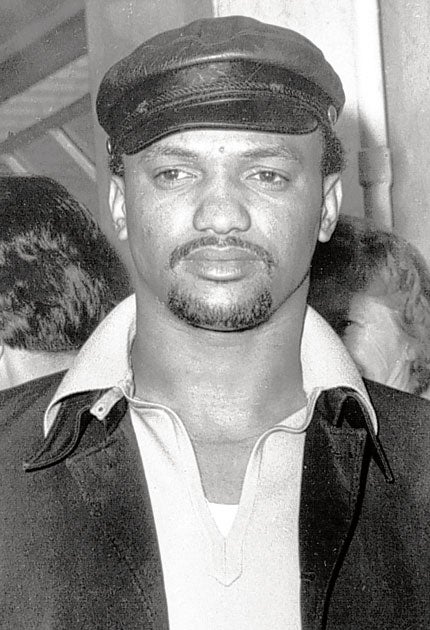

Geronimo Pratt: Black Panther leader who spent 27 years in jail for a crime he did not commit

America, it is assumed, does not make political prisoners of its own citizens. Not now, perhaps. But things were somewhat different in the racially charged era of the assassination of Martin Luther King and urban riots in major US cities – when the Black Panther leader Geronimo Pratt was sentenced to life in jail for a crime he almost certainly did not commit.

Pratt was convicted of the murder of Caroline Olsen and the serious wounding of her husband during a 1968 robbery at a public tennis court in Santa Monica, California, that yielded the killer just $18. Two years later, he was arrested and found guilty in 1972 after a trial that was little more than a judicial lynching.

In all, Pratt spent 27 years behind bars, eight of them in solitary confinement, before being released in 1997 when a judge ruled that prosecutors had withheld evidence that could have led to his acquittal. Eventually he received a $4.5m settlement for wrongful imprisonment and violation of his civil rights. Long before that, however, he had become an international symbol of racial injustice.

The son of a scrap dealer in the segregated south, Elmer Pratt grew up in wrenching poverty. Yet he was a clearly talented child who became the star quarterback at his local high school, before volunteering for Vietnam, where he served two tours, and was wounded and decorated for gallantry.

Taking advantage of the "GI Bill" that paid for the education of returning soldiers, he moved to Los Angeles and in 1968 enrolled at UCLA, where he studied political science. Those, however, were not ordinary times. Racial tensions were high and police violence rampant, and Pratt joined the radical Black Panther movement, where he quickly emerged as a potential leader, known as Geronimo Ji Jaga Pratt.

Inevitably, he came to the attentions of the FBI and its then boss J Edgar Hoover, who had declared the Panthers a mortal threat to the internal security of the United States and had launched the infamous COINTELPRO programme to infiltrate and destroy the movement. Pratt was a prime target, and the Olsen murder was an opportunity to bring him down. The only physical evidence was the presence of his car at the scene of the crime and a dubious identification by the victim's wounded husband.

The key prosecution witness, it later turned out, was an FBI informant inside the Panthers and a bitter rival of Pratt, while it later emerged that the FBI had – and did not disclose – wiretapping evidence confirming that Pratt was in Oakland, 400 miles away from Santa Monica, when the crime was committed. However all these exonerating circumstances were suppressed or ignored until 1997, and on 19 occasions Pratt was denied parole.

The reverberations of the casecontinued for decades. The attorney who unsuccessfully represented Pratt in the 1972 trial was the late civil rights lawyer Johnnie Cochran, who would later defend OJ Simpson – the black former football star whose 1995 acquittal on charges of murdering his wife may in part have reflected Los Angeles' collective folk memory of the Pratt case.

As Cochran later wrote, it "taught me and a lot of other lawyers never to accept the official version of an event, never accept a lab report, a forensic finding, never take so-called expert testimony at face value." Pratt himself, however, bore no outward grudges on account of his ordeal.

His death, in a village in Tanzania where he spent part of his time, was confirmed by Stuart Hanlon, another of Pratt's attorneys and a lifelong friend. "This became a microcosm of when the government decides what's politically right or wrong," Hanlon told The Oakland Tribune newspaper. "What happened to him is the horror story of the United States."

Elmer "Geronimo" Pratt, black activist and prisoner: born Morgan City, Louisiana 13 September 1947; married firstly Sandra (died 1971), 1976 Asahki (one son, one daughter); died Imbaseni, Tanzania 2 June 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks