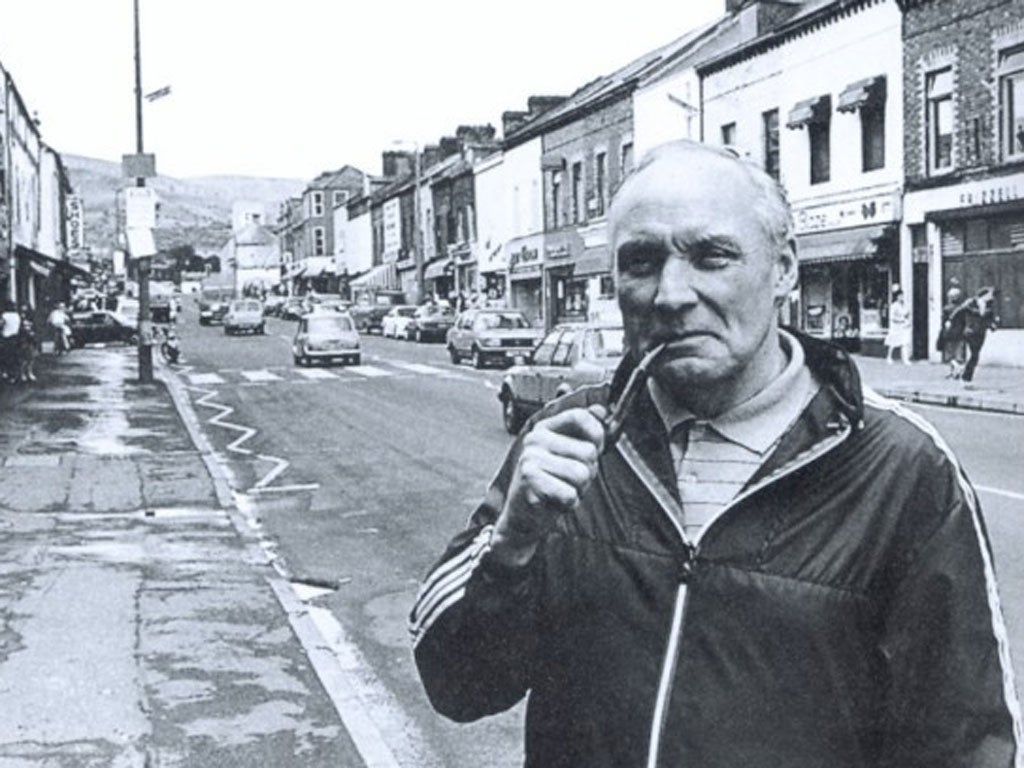

Gusty Spence: Loyalist terrorist who later became an advocate of peace in Northern Ireland

Gusty Spence was one of modern Belfast's earliest Loyalist gunmen, helping start the group which killed the first three victims of the Troubles. He was also the first of the hard men to repudiate violence and embrace the idea of peace. This duality led some to regard him as a man with much to answer for, while others commended him as a figure who had a genuine conversion to peaceful methods.

Most accept that his change of view was sincere. But not everyone has forgiven him for his involvement in murder and for launching the Ulster Volunteer Force which went on to claim the lives of almost 600 people. The charge against him is that he was a key figure in starting the Troubles.

Augustus Spence was born in 1933 in the Shankill Road district, one of Belfast's toughest Loyalist heartlands. His was a service family; his father Ned fought with the Royal Artillery in the First World War, while two of his brothers were in the Royal Navy and another in the Gordon Highlanders.

Housing conditions on the Shankill were fairly primitive, but local Protestants had the advantage over Catholics from the nearby Falls in terms of employment. His school was something of a roughhouse, Spence remembering that the headmaster "gave us some hammerings." Leaving school at 14, he found work in the shipyard and other engineering concerns which were largely Protestant preserves, before following in family tradition by joining the Royal Ulster Rifles.

The Rifles, which he described as one of the toughest regiments in the army, with extremely strict discipline, were despatched to Cyprus to deal with the emergency there. But after a few years he developed asthma and was discharged. He returned to work in the Post Office, but was sent to prison for claiming for overtime which he had not worked. "I was jailed for something I did, all right," he commented, "but it was custom and practice."

When the mid-1960s saw a mildly reformist Unionist government, the Reverend Ian Paisley and others cried treachery. Alarmed by this, Spence and others took to meeting in bars. He became commander of Shankill UVF, maintaining that he had been sworn in by a Unionist politician whom he never named. They prepared for a fight to the death with the IRA, which then barely existed. "I bought the first Thompson submachine gun that was ever seen on the Shankill Road," he remembered. "I paid 30 quid for it and 20 rounds of ammunition."

In May 1966 his group warned: "From this day we declare war against the IRA and its splinter groups. Known IRA men will be executed mercilessly and without hesitation." At first this was not taken seriously but within a month Spence's gang had claimed three lives. Although he always maintained he was not motivated by sectarianism, two of the victims were harmless Catholics who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The third was a Protestant widow in her seventies who was terribly burned when the gang attacked a Catholic-owned bar and accidentally set fire to her home. Spence was convicted of the murder of a teenage Catholic barman, Peter Ward, who was shot dead in the Shankill after leaving a local pub. He was also charged with a second killing but these charges were dropped.

He was affronted by the idea of the authorities pursuing Loyalists. When police raided his house he protested, "That's what you get for being a Protestant." In prison he embarked on various protests, including hunger strikes. But he and the UVF seemed to be fading into history until the Troubles erupted in 1969. Spence's methods were suddenly in back-street vogue: the ominous slogan "Gusty was right" is said to have appeared on a Shankill wall.

The violence brought about a revival of the UVF and other Loyalist groups. This meant that a stream of militant Protestants were sent to prison, where Spence took charge of them. He handled them with military discipline. When Long Kesh prison was opened to hold both Loyalists and IRA inmates he acted as a martinet, drilling them up and down in its compounds. On the outside, meanwhile, the UVF developed into a major killing machine, murdering many Catholics in shooting attacks and pub bombings.

Spence had four months of freedom in 1972 when, on parole to attend his daughter's wedding, he was "abducted" by the UVF. During that time young Loyalists flocked to the organisation, dazzled by his Scarlet Pimpernel image. Back in Long Kesh, however, he embarked on a period of reflection. "My real education began in jail, finding out about myths and legends," he recalled. "I had to find out the historical context of what led me to where I was – why people were prepared to do the most desperate things." He read political and history books and had many conversations with left-wing Republicans, enjoying their company and becoming fascinated by their views. He was to write that his "deeply held and lifelong opinions on most matters changed dramatically, and I learned not to be afraid of the truth, however embarrassing."

He grew to detest Unionist politicians who, he maintained, had duped working-class Protestants into violent actions. He came to describe himself as a moderate socialist. Various eyebrows were raised when he wrote to the widow of a Republican activist shot dead by the army, telling her: "I salute your husband as an honourable and brave soldier. He was a soldier of the Republic and I a Volunteer of Ulster."

Above all, he came to believe that violence was futile, preaching negotiation and compromise to his captive audience. He explained: "Politics to us was the art of the possible, and we could see no reason why we couldn't come to an accommodation." He resigned as UVF commander in Long Kesh and called for a ceasefire.

At this point a cruel irony came into play, for as he was leaving violence behind many were eagerly plunging into it. The UVF went on a vicious spree, carrying out almost 200 killings in a three-year period. Many of its most militant members were young men who Spence had personally sworn in during his time at large. Some were known as the Shankill Butchers because they attacked Catholics with butchers' knives and cleavers.

Spence sent many letters from prison to the UVF leadership advocating peace, but according to a UVF veteran, "We said to ourselves, 'Jail has made him soft.' Sometimes we even tore it up and one time somebody wrote 'bollix' across his document."

Following his release in 1984, Spence continued to advocate peace. One of his contacts was the Catholic Cardinal Tomas O Fiaich, whom he described as a friend. But it was not until 1994, after the IRA went on ceasefire, that the Loyalists followed suit. It was Spence who made the announcement, offering "the loved ones of all innocent victims over the past 25 years abject and true remorse".

Since then the UVF has dwindled in size, but has not disappeared altogether, carrying out shootings and occasional rioting. He was upset when his home was attacked by other Loyalists during a feud, and he had to move away from the Shankill. He did not run away from his past, though, contending: "Society has to be magnanimous and recognise the transformation of an individual, or else there can be no change. Regrets? My life is absolutely strewn with regrets. They have helped me influence people not to make the same mistakes that I made."

Augustus Spence, Loyalist activist: born Belfast 28 June 1933; married 1953 Louie (died 2003; three daughters); died Belfast 24 September 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks