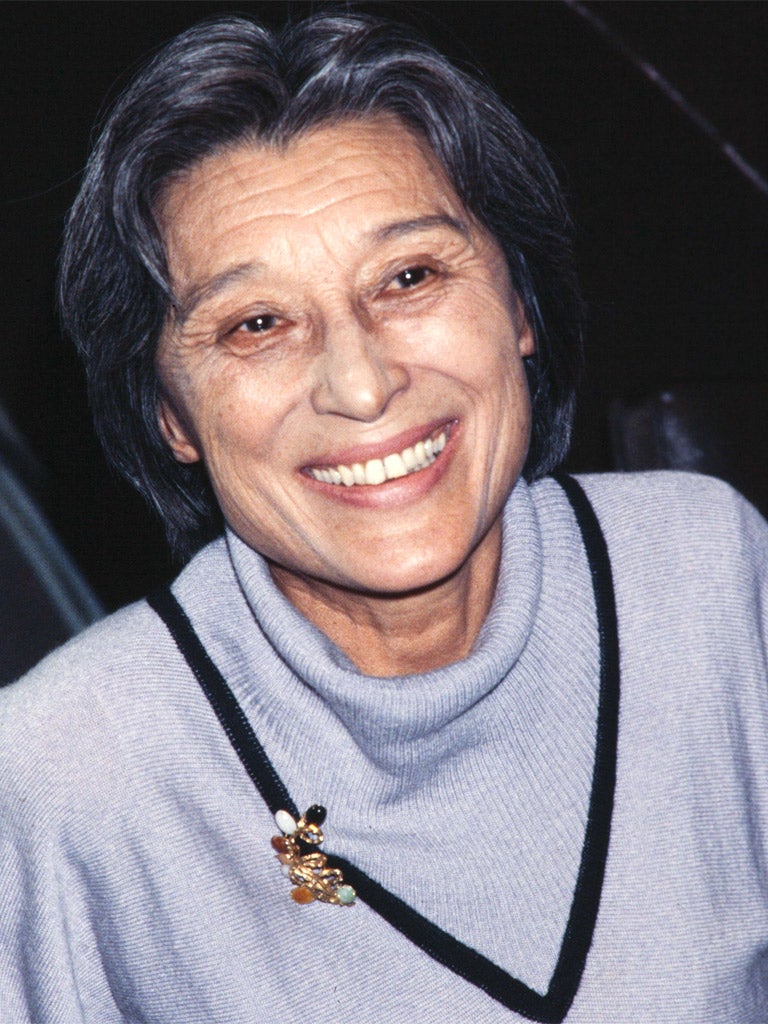

Han Suyin: Author whose best-selling 'Many-Splendoured Thing' became a Hollywood hit

Han Suyin came to the notice of the Western world with her bestseller love story published in 1952, A Many-Splendoured Thing. The novel, an account of her affair in Hong Kong with the journalist Ian Morrison, was made into a film, Love is a Many Splendored Thing, starring Jennifer Jones and William Holden, in 1955, which won two Academy awards.

Han Suyin wrote the work to assuage her grief after Morrison, a distinguished foreign correspondent for The Times, was killed in August 1950 while reporting from the front during the Korean War. It won her the American Anisfield-Wolf Award in 1953. Both film and book include poignant scenes by the tree where the couple said their last farewells.

The Twentieth Century Fox film, directed by Henry King, produced by Buddy Adler and scripted by John Patrick, turns Morrison, an Australian of Scottish descent educated in England, into "Mark Elliott", an American reporter. Its schmaltzy Hollywood theme song is far from the precise, delicately impressionistic style in which Han Suyin wrote her many books, using mostly English, but also French and Chinese.

She was born in 1917 in Sinyang, Henan province, on Mid-Autumn Day, China's ancient lunar harvest festival. The daughter of a high-class, prosperous Hakka Chinese father, Zhou Yintong, a railway inspector, and a Belgian mother, she spent her life trying to reconcile the elements in her of East and West.

She changed her name from Rosalie Mathilde to Elisabeth, retaining the given family name "Kuang" meaning "Shining", and set her heart on training as a doctor. This was the profession of Sun Yat Sen, leader of the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) and founder of the Chinese Republic in 1911, when the Manchu Dynasty was overthrown. "Science was our god," she wrote, in her first book Destination Chungking (1942), "a beneficent god to make China a rich and happy nation." She attended Yenching University, now part of Beijing University, and finished her medical training in Belgium and at the Royal Free Hospital in London.

All through her childhood she had known a China in turmoil, but she and her first husband, the Sandhurst-trained Tang Pao-huang, an officer on the General Staff of Sun Yat Sen's successor as Kuomintang leader, Chiang Kai-Shek, also experienced, she wrote, greater freedom than previous generations, especially in matters of social contact and being allowed to marry for love. "I grew into youth in that interval of peace when our country was united and all her factions in fair accord," she declared. "To be young was to be patriotic, to love China with a fierce fervour of pride." Nevertheless a shadow loomed: "It is true, if we paused to think soberly, there was a shiver of apprehension in the knowledge that Japan waited like a cat, watchful for her opportunity, poised to spring."

Flight from the Japanese was one of the experiences she shared with her later lover, Morrison: in 1938 she and Pao had fled the fall that October of the city of Hankow, and Morrison the fall of Singapore in February 1942. By the time she met Morrison in 1949 she was a widow, Pao having been killed fighting in Manchuria in 1947. The affair with Morrison drew attention to her Eurasian background, and she lost her job and faced ostracism by the Chinese community.

The state of being a refugee, first experienced in childhood when she and her mother had to flee warlords and go to Beijing, informed all her work, more than 20 books in English, spanning the last five decades of the 20th century, often about thwarted love. She also wrote biographies of Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, criticised by some as too adulatory, and travelled the world giving lectures.

A woman of contradictions, she declared herself in her twenties a pacifist, then devoted herself to supporting Chinese armed resistance to the Japanese. An advocate of freedom from colonial rule, in 1952 she married Leon Comber, a British Special Branch officer putting down communist revolt in Malaya in the Emergency as British control neared its end.

Comber, who survives her, told an interviewer in 2008 that they met in Hong Kong, and she followed him to Johore Bahru, Malaya. He felt that her novel about the time, And the Rain My Drink, presented the British security forces in a "rather slanted fashion... She was a rather pro-Left intellectual." The seven-year marriage ended in divorce.

Han Suyin continued her medical practice at Johore Bahru in her own name as Dr Elisabeth CK Comber, keeping her second husband's surname. She had chosen her pen-name, Han, in homage to the majority group of Chinese – the word also meaning "guest-people", or refugees – and Suyin, meaning "plain-sounding".

She met the man who was to be her third husband on a trip to Nepal in 1956. Colonel Vincent Ruthnaswamy of the Indian Army, whom she married in 1960, became with her a "friendship envoy" sanctioned by the Chinese People's Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries. This remit included repairing strains with India, after the war between India and China of 1962. Han Suyin was also a consultant to the World Health Organisation on China affairs.

She and Colonel Ruthnaswamy lived in Bangalore, then Hong Kong. He died in 2003. Her last years were spent living in Lausanne, Switzerland, about which, with her ever-inquiring mind, she made up a novel. That city's 18th-century clock industry is the subject of The Enchantress (1985), in which a brother and sister take the latest European technology to China but are obliged to flee back to Europe.

Han Suyin leaves an adopted daughter, Tang Yungmei.

Anne Keleny

Rosalie Mathilde (Elisabeth) Kuang Chou (Zhou), (Han Suyin), author and physician: born Sinyang, Henan, China 30 September 1917; married 1938 Tang Pao-huang (died 1947), 1952 Leon Comber (divorced 1959), 1960 Vincent Ruthnaswamy (died 2003); one daughter; died Lausanne, Switzerland 2 November 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks