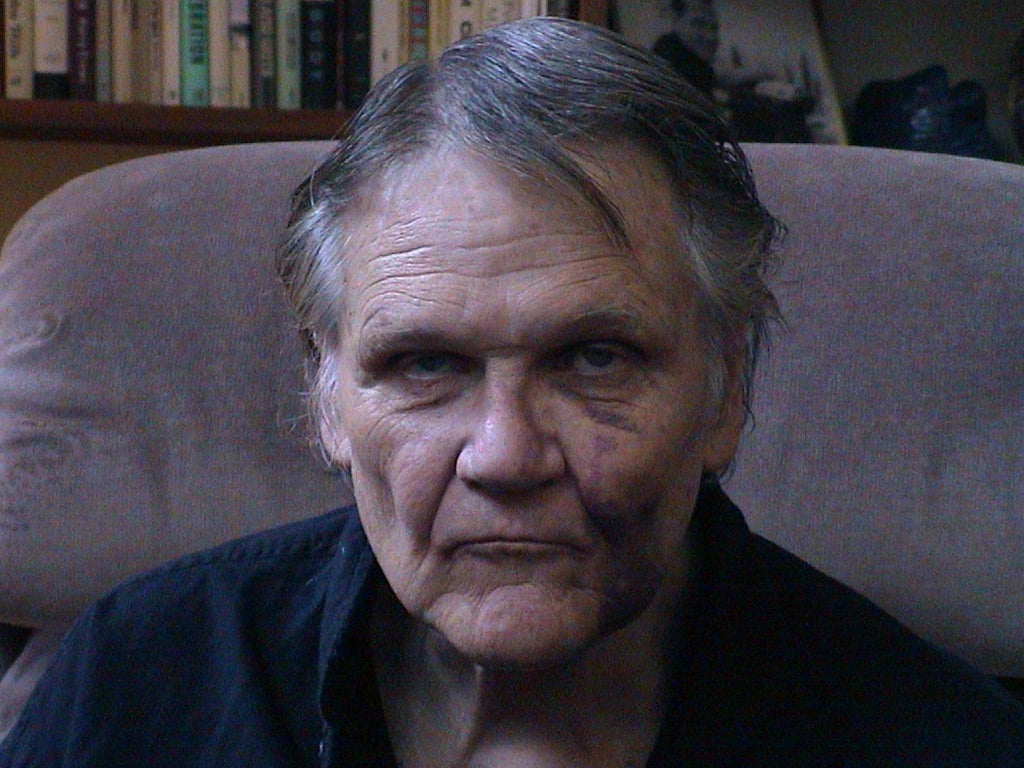

Harry Crews: Hard-drinking, hell-raising writer whose work was full of freaks and grotesques

Harry Crews was for many years professor of creative writing at the university of Florida, producing novels and journalism which brought him a considerable cult following.

He was conspicuous on campus due to his Mohawk haircut and skull tattoo which proclaimed "How Do You Like Your Blue-Eyed Boy, Mr Death?" Students were fascinated by his boisterous lectures and his reputation as a hell-raiser and bar-room brawler whose legendary alcoholic consumption almost killed him many years before his death.

He was thus no conventional academic or literary figure, but rather a self-absorbed character who was as devoted to writing as he was to self-projection, both in life and on the page. He was almost obsessively devoted to the craft of writing. He said: "Once I take hold of something I work long – too long, probably – and I never miss a day."

He created and immersed himself in a world of freaks, psychopaths and lowlifes in a genre which has been called grit-lit and southern grotesque. One of his characters ate a car, bit by bit; another would punch himself unconscious. His characters were described as "usually damaged people with a jaded world view."

He lived life as though he was in one of his own books. The American journalist Steve Oney said: "To say that Harry was prone to trouble is an understatement. He rarely backed down from a fight. He drank too much. He never met an attractive woman he didn't try to seduce. Strange and sometimes terrible things simply happened to him, but he would have had it no other way. He called his philosophy 'getting naked', and if it led him into some jams it also helped him to produce works of fiction that could take your breath away."

His books both mirrored and exaggerated his tough childhood. He was born in the Georgia swamplands, where his father died when he was two. It was, he said, "the worst hookworm-and-rickets part of Georgia," with people so poor they absorbed minerals by eating clay.

His mother married his father's brother but left because of his drinking and his habit of firing a shotgun in the house. At the age of five an unknown disease deformed Crews' legs, a condition which brought locals to gawk at him. He felt like something in a carnival, "how lonely and savage it was to be a freak."

Later he was seriously scalded when he fell into hot water, but he recovered and at 17 followed his brother into the Marines. He explained sardonically: "We did the good, southern, ignorant country thing, anxious as we were to go and spill our blood in the good, southern, ignorant country way."

In the Marines Crews was able to indulge his appetite for reading, devouring Mickey Spillane – and Graham Greene, who he said was "the man to whom I owe the greatest debt". Convinced he was to be an author, he took advantage of the GI Bill to go to university, writing "like a house afire" and studying for two degrees. But he found college life suffocating and dropped out, writing later: "At the end of two years, choking and gasping from Truth and Beauty, I gave up on school for a Triumph motorcycle."

He spent two years travelling around the US, working in a carnival and as a bartender and short-order cook. He was thrown in jail in Wyoming and was proud of having been "beaten in a fair fight by a one-legged Blackfoot Indian" in Montana.

Once in the swing of writing, he produced two dozen books including A Feast of Snakes, which centres on a rattlesnake round-up in Georgia; The Gypsy's Curse, whose central character, a bilateral amputee, walks everywhere on his hands; Florida Frenzy, a collection of essays and stories; All We Need of Hell, featuring a lawyer going spectacularly off the rails; and This Thing Don't Lead to Heaven, an account of Gothic doings in an old people's home.

His biggest challenge was producing an autobiography, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, which chronicled the horrors of his upbringing and the traumas of his adolescence. "Writing that book damn near killed me," he recalled. "I thought if I wrote all that stuff down, in as great a detail as I possibly could, talking to as many people as I could and reliving it, it would be cathartic. I thought that it would in some sense relieve something. And it may have, but it didn't do what I thought it would do. It didn't work out that way."

He also wrote extensively for magazines such as Esquire and Playboy, producing formidable quantities of work even as he consumed formidable quantities of liquor. He often went into bars looking for trouble, flaunting his hair-do and tattoo. "I walk into some places," he said, "and among other things I feel animosity, disapproval and sometimes rank hatred, coming off the people like heat off a stove."

Much of the literary world also exuded animosity. His work was not the stuff of bestsellers, but it attracted a cult following and was reviewed in publications like the New York Times. He scorned his critics as "dumbasses out there watching television until they are rotting in their souls, who cannot read my fiction and who say that it's gratuitous. I say they have no eyes, no ears, no heart, no mouth, no sympathy, no charity for the human predicament."

Eventually he got his drinking under control. "Alcohol whipped me," he wrote. "Alcohol and I had many, many marvelous times together – we laughed, we talked, we danced. Then one day I woke up and the band had gone home and I was lying in the broken glass. All that drinking is a movie I wish I could have missed, I really do. But a lot of stuff happened that I never would have learned otherwise, because I was in places I'd never have been otherwise."

He retired from university in 1997, with enough money to live comfortably. He twice married Sally Ellis and twice divorced her. They had two sons, one of whom drowned as a child. Their surviving son, Byron, is an academic.

Harold Eugene Crews, writer and professor of literature: born Bacon County, Georgia 7 June 1935; married Sally Ellis (one son, and one son deceased); died Gainesville, Florida 28 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks