Helmut Schmidt: Politician who guided West Germany through tough economic times, terrorism and the Cold War

His legacy is a country seen by itself and others as an island of well-managed stability in Europe

West Germans rebuilding their shattered and divided country after the Second World War mostly chose chancellors who nicely fitted the needs of their time. Dr Adenauer moulded the democratic foundations of the fledgling state and cemented it into the Western alliance. Ludwig Erhard completed the “economic miracle” of postwar recovery. Willy Brandt achieved reconciliation with his eastern neighbours.

Helmut Schmidt, Chancellor from 1974-82, consolidated the work of all three, guiding his country with iron determination through the oil crisis, domestic terrorism and growing friction with the US (to which he contributed). He was also a dominant figure in Europe, working with Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, French Finance Minister and later President, to set up the European Monetary System. More controversially, he precipitated Nato's decision in 1979 to deploy new nuclear missiles in Western Europe.

Most of the West German public had great confidence in him and many crossed party lines to vote for him. Abroad, he was admired as a statesman of intellect and vision. Only his own Social Democrats never felt comfortable with his cool, sharp realism, his impatience with socialist shibboleths, and, above all, his acceptance of nuclear weapons. In the end he achieved less than he had hoped for, thwarted by Britain's lack of interest in Europe, his inability to get on with President Carter, the oil crisis and the leftward drift of his own party.

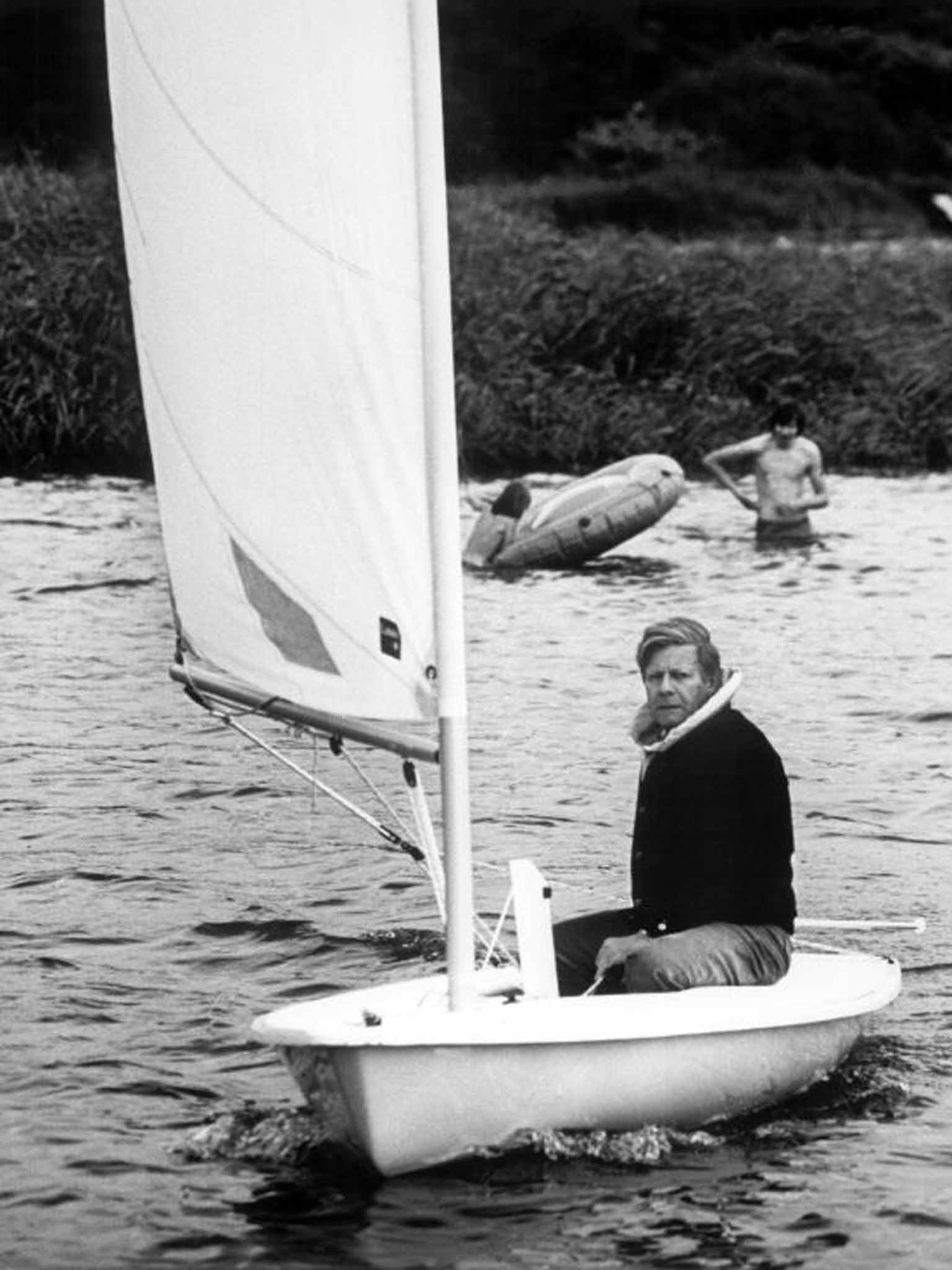

Yet he was probably the most effective chancellor in the short history of West Germany, an often brusque and didactic workaholic with detailed knowledge of issues, particularly defence and economics, and the ability to master new subjects quickly. He had intended to be an architect, and he read widely, especially in philosophy. While Chancellor he appointed a retired journalist to read the latest books for him and keep him up to date. He discussed religion long into the night with President Sadat of Egypt, loved music, made friends with Leonard Bernstein, and played the piano well. Once he took a day off from government to fly to London and record Mozart's concerto for three pianos with the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

The two sides of his character probably reflected the contrast between his parents. His father was an austere teacher who believed in hard work and the repression of emotions: Helmut was told not to cry when he fell over. His mother was artistic and musical and took her children to concerts and exhibitions.

Schmidt was born in 1918 in Barmbek, a working-class district of Hamburg. He went to the Lichtwark school, a relatively liberal place later closed by the Nazis. He was bright, hard-working, good at English and head of the rowing team. One of his classmates was Hannelore Glaser, whom he married in 1942. When his rowing club was assimilated into the Hitler Youth he became a member, but he objected to Nazi views on art and was expelled for writing on the rowing club wall a phrase about freedom “shining like a beacon across the world”.

However, he showed few other signs of interest in politics. He was conscripted in 1937 and posted to an anti-aircraft battery in 1939. He spent some years with an anti-aircraft unit at Leningrad and in the advance towards Moscow. After a period as an instructor in Berlin he was moved to the Western front, where he was captured by the British in April 1945.

Reflecting later on the Nazi period he would say he knew the regime was criminal and that it would collapse but, like most of his compatriots, kept his views to himself. He was not especially politically aware, with little knowledge of democracy. This began to change in a British POW camp, where he was influenced by Social Democrats among his fellow prisoners.

Yet, even after joining the Social Democratic Party in 1946, he was never wholly comfortable in it and never fully accepted. His army service made him suspect among comrades whose faith had been forged in opposition, exile or concentration camps. His thinking was shaped more by his frugal childhood, school and the army, followed by near starvation amid the ruins of a defeated country. His first child died, and when his second was born in 1947 the family was living in a single rented room. He was impatient with ideological discussion and reconstructing Germany as an urgent practical matter.

Finding that he would have to travel to Hanover to study architecture he settled for economics at Hamburg, graduating in 1949. While still a student, he became known among Social Democrats as a good organiser and effective, if rather arrogant, speaker. He quickly found a job in the Hamburg government, and in 1953 was elected to the federal parliament in Bonn, at first specialising in transport but gradually making his mark as an expert on defence. He became known as a critic of the government, earning the nickname “Schmidt Schnauze” (roughly “Schmidt the lip”).

In 1958 he won applause for speaking out against allowing the West German army access to nuclear weapons. He also made an important speech calling for arms reductions in central Europe, including reductions in foreign troops. But he then lost the credit he had gained among the party faithful by taking part in military manoeuvres as a volunteer and being promoted to captain in the reserve. As a result he was voted off the parliamentary executive.

In 1959 he supported the “Bad Godesberg Programme” under which the Social Democrats dropped a lot of their Marxist baggage and accepted membership of Nato. But when the party lost the 1961 election Schmidt, impatient with opposition, took a job in the Hamburg state government as Minister for Internal Affairs. A few months later floods killed more than 300 people in the area and Schmidt shot to prominence organising the relief effort.

He returned to Bonn in 1965, becoming deputy leader of his parliamentary party and then its leader in a “grand coalition” with the Christian Democrats. In 1968 he was chosen as deputy leader of the Social Democratic Party under Brandt, a post he held until 1984.

The coalition pulled the economy out of trouble but was unable to develop an effective eastern policy because of opposition from the Christian Democrats. By 1969 the Free Democrats were ready to join a coalition with the Social Democrats. Brandt became Chancellor and invited Schmidt to become Defence Minister, the first Social Democrat in the job since the 1920s. He assembled a bright think-tank, cut the period of conscription from 18 to 15 months and introduced other reforms.

He supported Brandt's policy of détente with eastern neighbours, having played an active part in its evolution since 1966, when he travelled privately to Eastern Europe. In 1972, after a severe viral infection and thyroid problems, he succeeded his old mentor Karl Schiller as Minister of Economics and Finance, later becoming Finance Minister. It was at this time, with exchange rates under severe stress and the need for international co-operation growing, that he began his long association with Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, French Finance Minister at that time and later President of France.

In May 1974 Brandt, already tiring, resigned on discovering that one of his closest advisers, Günter Guillaume, was an East German spy. Schmidt took over, though still distrusted by the party's left wing. Later he wrote scornfully of the “euphoric planners, system-changers and neo-Marxists” who could not understand the impact on West Germany's economy of dramatic changes in the global economy following the oil price explosion of the early 1970s.

He won the 1976 election by a narrow margin, his own popularity running far ahead of that of his divided party. He soon faced new stresses when a wave of domestic left-wing terrorism hit West Germany. He did his best to balance the civil liberties against the need for security and as a result he was attacked by right and left. One of his worst moments came when German terrorists kidnapped Hanns-Martin Schleyer, President of the Employers' Federation, and offered to exchange him for 20 of their imprisoned members. Schmidt refused.

The terrorists hijacked a Lufthansa jet and forced it to fly to Mogadishu, threatening to kill all on board. Schmidt took the risky decision to let West German forces storm the jet. Prepared to resign if the action failed, he reaped credit for its brilliant success. Some of the imprisoned terrorists committed suicide and Schleyer was murdered but the episode marked the beginning of the end of the terrorist campaign.

Foreign affairs became increasingly difficult. Schmidt was aware of both the dangers and the opportunities created by the rise of West German economic power; he concluded that West Germany must operate within the framework of the EC and the Nato alliance.

He was perpetually disappointed by the British attitude to Europe, and especially impatient with Labour, but he put his case with courtesy and humour in a masterly speech in excellent English to the Labour Party conference in 1974. He had a deep respect and affection for James Callaghan, Prime Minister from 1976-9, whom he saw as equally undermined by left-wing ideologues. He was especially grateful to Callaghan for providing British advice and stun grenades for the Mogadishu incident and for supporting him through bitter European debates on nuclear weapons.

When the Soviet Union started deploying a new generation of intermediate-range missiles, SS-20s, aimed at Western Europe, Schmidt went public with his worries in a speech to the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London in 1977. This triggered a debate that culminated in Nato's decision to deploy Pershing II and cruise missiles in Western Europe in 1983 if by then no agreement had been reached with the Soviet Union on reductions.

A wave of public protests swept Europe, especially after President Reagan alarmed many by abandoning détente. The Western peace movements were supported by Moscow and East Germany, whose leaders hoped the demonstrations might prevent deployment. Schmidt paid a heavy price because the issue split his party and contributed to his downfall in 1982..

The fact that Schmidt's loyalty to the West was unquestioned had made it easier for him to continue the Eastern policies initiated by Brandt. He fostered contacts with Moscow and Eastern Europe and used Germany's economic power to gain political leverage, sharply increasing aid, trade and investment in the area. He was contemptuous of President Carter, whose emphasis on human rights would, he feared, destabilise Eastern Europe and provoke more Soviet repression. His blunt private comments on Carter, whom he regarded as a bungling amateur, reached Washington, and there was a fierce personal confrontation in Vienna.

Reconciling an active Eastern policy with loyalty to the West had become more difficult after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. When Reagan turned his back on détente many West Germans feared his confrontational approach would destroy their relations with their eastern neighbours. In 1980 Schmidt made it clear that European détente was Germany's overriding interest by becoming the first Western leader to visit Moscow after the invasion of Afghanistan.

Although re-elected in 1980, Schmidt came under increasing strain as Atlantic relations deteriorated and his party moved to the left. In 1981 he was fitted with a pacemaker, then in autumn 1982 his coalition with the Free Democrats collapsed and he was deposed as Chancellor by a parliamentary vote of no confidence, opening the way for the Christian Democrats to take over under Helmut Kohl. He remained a member of the Bundestag until 1987.

In 1983 he became co-publisher of the Hamburg weekly Die Zeit, throwing himself into editorial discussions. In his new career as journalist, writer and lecturer he set himself up as the scourge of those Western leaders (most of them, in his view) who failed to measure up to his standards. He told everyone who cared to listen (and many did) that the Western world suffered from mediocre leadership and a lack of strategic vision. Critical of Britain's hesitant approach to Europe, he formed a pressure group with his old friend Giscard d'Estaing to press for monetary union, and urged Britain to join, appearing on the BBC to attack “good old English stubbornness”.

Schmidt welcomed German reunification but was critical of Chancellor Kohl for failing to warn the German people of the true costs. He remained active into his mid-eighties, and despite smoking, and suffering another heart attack in 2003, he continued to lecture around the world and filled large halls in Germany, also regularly lecturing Die Zeit editors on the state of the world. He continued to paint and play the piano. A practising Protestant, he sometimes preached in church.

He wrote many articles and a number of books, including A Strategy for the West (1986), People and Power (1987), The Germans and their Neighbours (1990) and Memories and Reflections (1996). He was also showered with honours, including honorary doctorates from Harvard, Oxford, Cambridge and the Sorbonne.

His legacy is a country seen by itself and others as an island of well-managed stability in Europe. But his strengths were also his weaknesses. He was perhaps too impatient with those whose feelings ran counter to his, so lost touch with some of the emotional undercurrents that drive politics and alienated many who might have been more supportive. In his relations with President Carter he let his emotions get the better of him, widening the abyss of misunderstanding. Yet he was an impressive figure who increased the stature and confidence of his country and left it in better shape than he found it. Many Germans continued to revere him long after he left office.

Helmut Heinrich Waldemar Schmidt, politician, economist and writer: born Hamburg 23 December 1918; married 1942 Hannelore Glaser (died 2010; one daughter, and one child deceased); died 10 November 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks