Hermínio Martins: Sociologist who explored the dangers of 'digital capitalism' and the power imbalance between Portugal and Brazil

He succeeded in illuminating obscure areas of the social world, exploring many fields untouched by other theorists and developing sociology as an "historical discipline of philosophical reflexion"

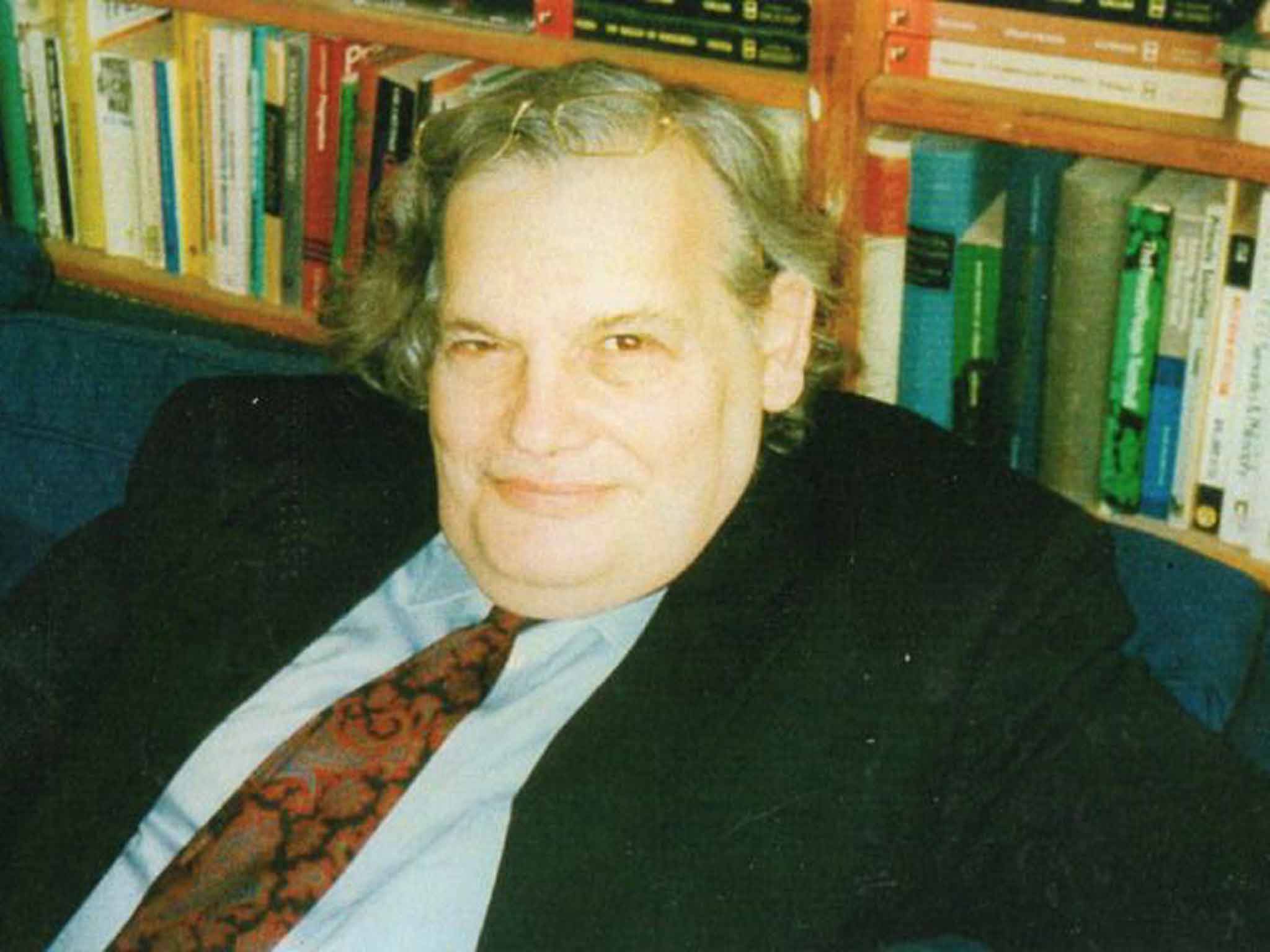

The death of the Portuguese-British sociologist Hermínio Martins will be mourned by social scientists internationally, impressed by his extraordinary erudition and the subtlety of his irony. He had a marvellously sardonic eye for fashionable intellectual excesses, yet accompanying this was a deeply held set of secular values, stemming from the Enlightenment.

This emancipatory realism appeared early in his outstanding analysis of the sociology of knowledge The Kuhnian 'Revolution' and its Implications for Sociology, in which he sought to establish grounds for rationalism despite Kuhn's epistemological relativism; moreover, he held such a perspective to the end, as in his withering dissection of the rampant marketisation of universities, The Marketisation of Universities and some Cultural Contradictions of Academic Knowledge-Capitalism, in Metacritica. Throughout his life he succeeded in illuminating obscure areas of the social world, exploring many fields untouched by other theorists and developing sociology as an "historical discipline of philosophical reflexion".

He was born in 1934 in Mozambique, then part of the Portuguese empire. After his mother's death when he was five, his maternal aunt and his uncle, a land surveyor, brought him up. He attended the Liceu Salazar school in Mozambique, where he became an opponent of Portuguese imperialism. Refusing to go to a South African university because of apartheid, he made his way to Britain, attracted not least by leading Marxist intellectuals of the day.

Registering at the LSE in 1954 for a degree in economics and taught by Karl Popper, he specialised in sociology in his third year. It was in this discipline, supervised by Ernest Gellner, that he launched his initial postgraduate study of Emile Durkheim. In 1959, Martins was appointed to a lectureship in sociological theory at Leeds University, then at Essex University when it opened in 1964. He spent two years in the US, as visiting lecturer at Harvard (1966-67) and then at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (1967-68).

He was appointed in 1971 to the Latin American Centre at St Antony's, Oxford, to teach the sociology of Latin America. He supervised a large number of D Phil students, whose published books recall him fondly. He remained at St Antony's until retiring in 2001, then taught and supervised at the University of Lisbon, until he had to retire from there as well.

Relegated before the 1974 Carnation Revolution to the category of "stateless person", Martins became one of those distinguished exiles who contributed so much to British sociology, helping transform the subject. Apart from numerous influential articles, he edited and co-edited a number of books, including Knowledge and Passion (a Festschrift for John Rex, 1993) and a volume co-edited with M Angela d'Incao on the former Brazilian president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Democracia, Crise e Reforma, published in Brazil in 2010.

He was awarded an honorary doctorate at Lisbon (2006) and two Portuguese Medals of Honour, as well as a festschrift. Another conference to mark his 80th birthday took place in Portugal last year.

Martins had three major themes. The first was the need to understand and explain the underlying authoritarianism of Portuguese-Brazilian social relations, without adopting what he called "the retrospective illusion of fatality". The second theme concerned the new institutions and attendant dangers of digital capitalism, bioinformatics and robotised immaterial labour.

The third concerned the threats posed by the processes of marketisation and bureaucratisation in universities. Martins possessed great originality, especially in the sociology of science, where his work on Kuhn helped renew a neglected terrain of study. But he also revealed an unusual approach to the sociology of Portuguese fascism, emphasising the modernising aspect of the Portuguese dictatorship despite the appearance of "time standing still".

He specialised in two other rare fields: the sociology of time and of technology. In the latter he wanted to contribute to the Kantian tradition of social and cognitive criticism. Indeed, to Kant's three critiques – of Reason, Practical Reason and Judgement, Martins pioneered a "critique of technological reason". Emphasising the naïveté of the all-pervasive celebration of the new IT age, including its robotic scientists and designer babies, he raises serious questions about the facile substitution of a "transhuman age" for our more familiar "human age".

This is, in its way, a radical humanism – an investigation seeking to alert us to the dangers immanent in the passion for "the power and the glory of machinehood" in the interests of more sober emancipatory goals. In brief, if Marx and Weber as classical sociologists, shared the same cultural pessimism about hegemonic capitalism, Martins possessed a similar critical eye for the cyber-technological mode of production.

He had an unusual capacity for charting "the new", but his immersion in this sphere was always to show how technology might be misused in the interests of power . We should lament the loss not only of a pioneer but also a social critic, a man who extended to new territories the Hippocratic precautionary principle: "do no harm!"

***

Hermínio Martins was a central figure to an understated, though far-reaching, academic community around his presence. His generous open invitation to welcome Portuguese-speaking colleagues and students to lunch at St Antony's College every Tuesday, at the celebrated Mesa Lusófona, fostered a dialogue that flowed through ideas and fuelled by food and the following coffee in the Common Room. Sociologists of different inclinations, philologists, historians, writers, lexicographers, scholars of various sciences, all communed in a frank exchange of ideas tempered by Hermínio's input and keen interest in it all. In a sense, the Mesa Lusófona epitomises Hermínio's little known work of far-reaching impact – the list of contributors of the Oxford Portuguese Dictionary is testament to that. Luis Gomes

Hermínio Gomes Martins, sociologist: born Lourenço Marques, now Maputo, Mozambique 20 June 1934; married 1959 Margaret Stanbridge (one son, and one son deceased); died Oxford 19 August 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments