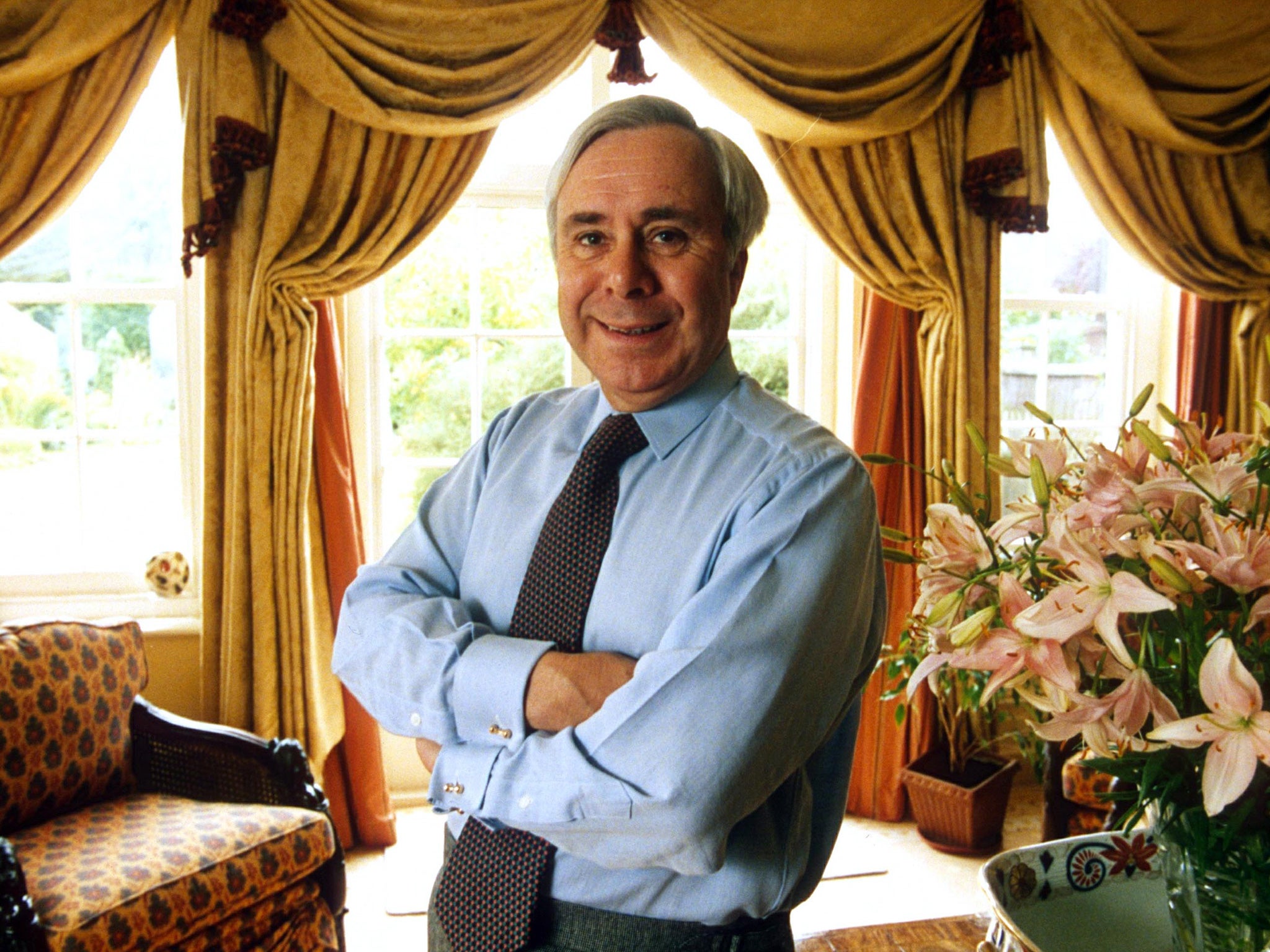

Ian Greer: Parliamentary lobbyist whose successful business was brought down by the 1990s 'cash for questions' scandal

Greer was brought down by an allegation that two Tory MPs, Neil Hamilton and Tim Smith, had been paid by Mohamed al-Fayed, owner of Harrods, to table questions in the House of Commons

Ian Greer was the most successful lobbyist in Westminster, until a “cash for questions” scandal damaged his reputation and ruined his business. His heyday was in the 1980s and early 1990s, during the long period of uninterrupted Conservative government, when the rules governing the interaction between MPs and private business interests were, by contemporary standards, shockingly slack. “There was a shamelessness in the actions of many MPs,” he recalled in his memoir, One Man's Word. “In an era when City yuppies boasted of the size of their bonuses, parliamentarians shared tales of their freebies.”

Half the Cabinet, including the Prime Minister, John Major, turned out to the party in 1992 which celebrated the 10th anniversary of the launch of Greer's highly successful business, Ian Greer Associates. At its high point the business employed more than 50 staff and was valued at more than £3m. Within five years of that star-studded celebration, the receivers had been called in and Greer's lobbying days were over.

He was brought down by an allegation first published in The Guardian on 19 October 1994, that two Tory MPs, Neil Hamilton and Tim Smith, had been paid by Mohamed al-Fayed, owner of Harrods, to table questions in the House of Commons. The going rate was reported to be £2,000 per question. Greer was named as the go-between, the man who handed the MPs their money.

The revelation did huge damage to the already weakened government. Tim Smith, a new junior minister for Northern Ireland, admitted taking money from Fayed, though not from Greer. He resigned from the government and left Parliament at the election. Major reacted by creating the Committee on Standards in Public Life. But both Hamilton and Greer denied The Guardian's allegations and announced their intention to sue for libel.

This put Greer in the unenviable position that his reputation was now tied to Neil Hamilton's. Hamilton was in the public eye for three years, until he lost Tatton, one of the safest Tory seats in the country, to the anti-corruption campaigner Martin Bell in 1997.

Three days before Greer and Hamilton were due to begin their libel action, three of Fayed's present or former employees claimed to have handed over cash to Hamilton and Greer. The two fell out so badly that the libel action had to be called off. An official inquiry by Sir Gordon Downey later concluded that while Greer had not taken money from Fayed, Hamilton had. That was too late to save Greer's business.

Born in 1933, the son of a couple who had met through the Salvation Army, Greer went to work for Conservative Central Office at the age of 24, and became the party's youngest ever area agent. He left in 1966 to run the Mental Health Trust and created his first network of political contacts to help in his campaign for better conditions for the mentally ill.

In 1970 he went into business with John Russell, running a consultancy, but that partnership broke up acrimoniously after 10 years and Greer set up on his own. Part of the reason for the bust-up was Greer's keenness to take up American-style lobbying, which was more open and sharp-elbowed than the old boy networks that ran Britain's lobbying industry.

Most of Greer's political contacts were in the Conservative Party, though he was able to enlist Labour MPs such as Walter Johnson, MP for Derby South, who was paid by Greer in the early 1980s to campaign to retain lead in petrol. But Greer's best contact by far was the Conservative MP Michael Grylls, father of the adventurer Bear Grylls. A detail from the Downey Report that did Greer irreparable damage was that he had lied about paying Grylls.

In the mid-1980s, Greer prospered as big corporations discovered the value of hiring lobbyists. Plessey, the Argyll Group, Johnson and Matthey, the National Nuclear Corporation, and the House of Fraser, run by the Fayed brothers, joined his glittering list of clients. One of the greatest services Grylls performed for him was in July 1984, after the Civil Aviation Authority had produced a report criticising British Airways' near monopoly of air routes, to the fury of BA's powerful chairman, Lord King. Grylls, who chaired the Conservative Trade and Industry Committee, had a private meeting with King and recommended that BA hire Greer's firm, an account worth more than £100,000.

Grylls' secretary was a tough young woman named Christine Holman, who married Neil Hamilton five days before he was elected MP for Tatton in 1983, and introduced him to Grylls and to Greer. In his memoirs, Greer described an occasion when Christine Hamilton wanted to join her husband in America and asked for a free courier ticket on BA and a free upgrade to business class. “My patience was wearing thin,” Greer wrote, but it was arranged, along with a free limousine waiting to collect her at JFK airport. It came as a shock to King how many Conservatives linked to Greer thought themselves entitled to free BA flights.

Greer's homosexuality was an open secret in Westminster. He and his long-term partner, Clive Ferreira, were accepted as a couple years before civil partnerships were recognised. In retirement, he caused a stir by claiming on Radio 5 that there were 40 or 50 gay MPs in the Commons, though he never named names. He and Clive moved to South Africa after the collapse of his business with their dog, Sir Humphrey. There, Greer set up a soup kitchen for homeless children. He returned to London in 2013, to marry Ferreira, who survives him.

Ian Bramwell Greer, political lobbyist: born 5 June 1933; married 2013 Clive Ferreira; died 4 November 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks