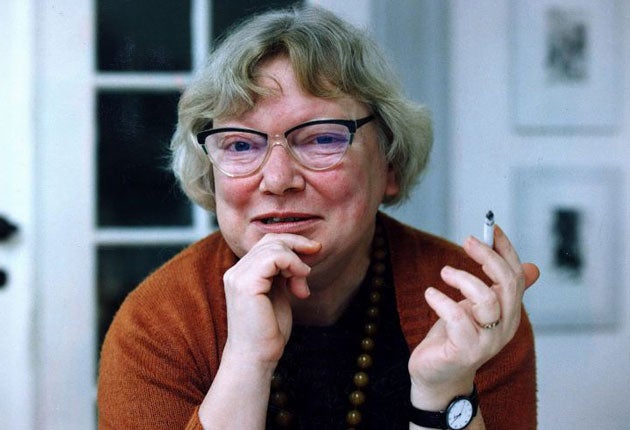

Inger Christensen: Experimental poet who used mathematical structures in her work

Inger Christensen was one of Denmark’s most innovative experimental poets. She is perhaps best known for her major poem “Alfabet” (“Alphabet”, 1981), a systematic work which uses the letters from “a” (beginning with apricots) to “n” (nights), coupled with the Fibonacci mathematical sequence (0,1,1,2,3,5,8...), representing growth in nature.

Christensen was born in 1935 in Vejle, on the eastern coast of Denmark. Following high school and teacher training college she taught for two years at the College for Arts in Holbæk and subsequently chose to take up writing full time, a decision in which she was encouraged by Poul Borum, whom she married in 1959. Her first volumes of poetry, which emerged during this period, Lys (Light, 1962) and Græs (Grass, 1963), examine the relationship between creativity, language, perception and the self.

Alarger collection of poetry, Det (It), was published in 1969 and reflected an era of upheaval and social change across the Western world. A poem from this volume, “The Action: symmetries”, chants in frustration:

Society can be so petrified

That it’s all one solid block

Inhabitants so ossified

That life’s in a state of shock

Much of Christensen’s work makes use of “systematic” structures on which she hangs her words, as in Alfabet.

Here she used the Fibonacci sequence (where the first number is 0, the second is 1 and the subsequent numbers are the sum of the previous two) to stipulate the number of lines for each stanza of this poem. “The numerical ratios exist in nature,” Christensen explained. “The way a leek wraps around itself from the inside, and the head of a sunflower, are both based on this series”. In short, Christensen sought in her poetry the mathematical representation of perfection in the natural world.

While one might ordinarily assume that such self-imposed and artificial constraints would restrict creativity Christensen’s poetry thrives on a playful interaction between the formalised structure and the text. After all, she viewed poetry as being just “a game, maybe a tragic game – the game we play with a world that plays its own game with us.”

Her last collection of poetry, Sommerfugledalen (The Butterfly Valley, 1991), is in the form of a sonnet cycle and is concerned with the ideas of death, hope, rebirth and transformation.

Christensen also wrote novels, short stories and essays, several of which are collected together in Hemmelighedstilstanden (The State of Secrecy, 2000).

Christensen was elected to the Royal Danish Academy in 1978 and was recognised with the Austrian Prize for Literature (1994), the Swedish Academy’s Nordic Prize (1994), the Grand Prix at the International Poetry Biennal (1995) and the Siegfried Unseld award (2006), among others.

The British publisher, Bloodaxe Books, which has brought out some of Christensen’s work in English translation, observed that her work had: “...a visionary quality; yet she is a paradoxically down-to-earth visionary, focusing on the simple stuff of everyday life and in it discovering the metaphysical as if by chance.”

Marcus Williamson

Inger Christensen, experimental poet: born Vejle, Denmark, 16 January 1935; married Poul Borum 1959 (one son; divorced 1976); died Copenhagen, Denmark, 2 January 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks