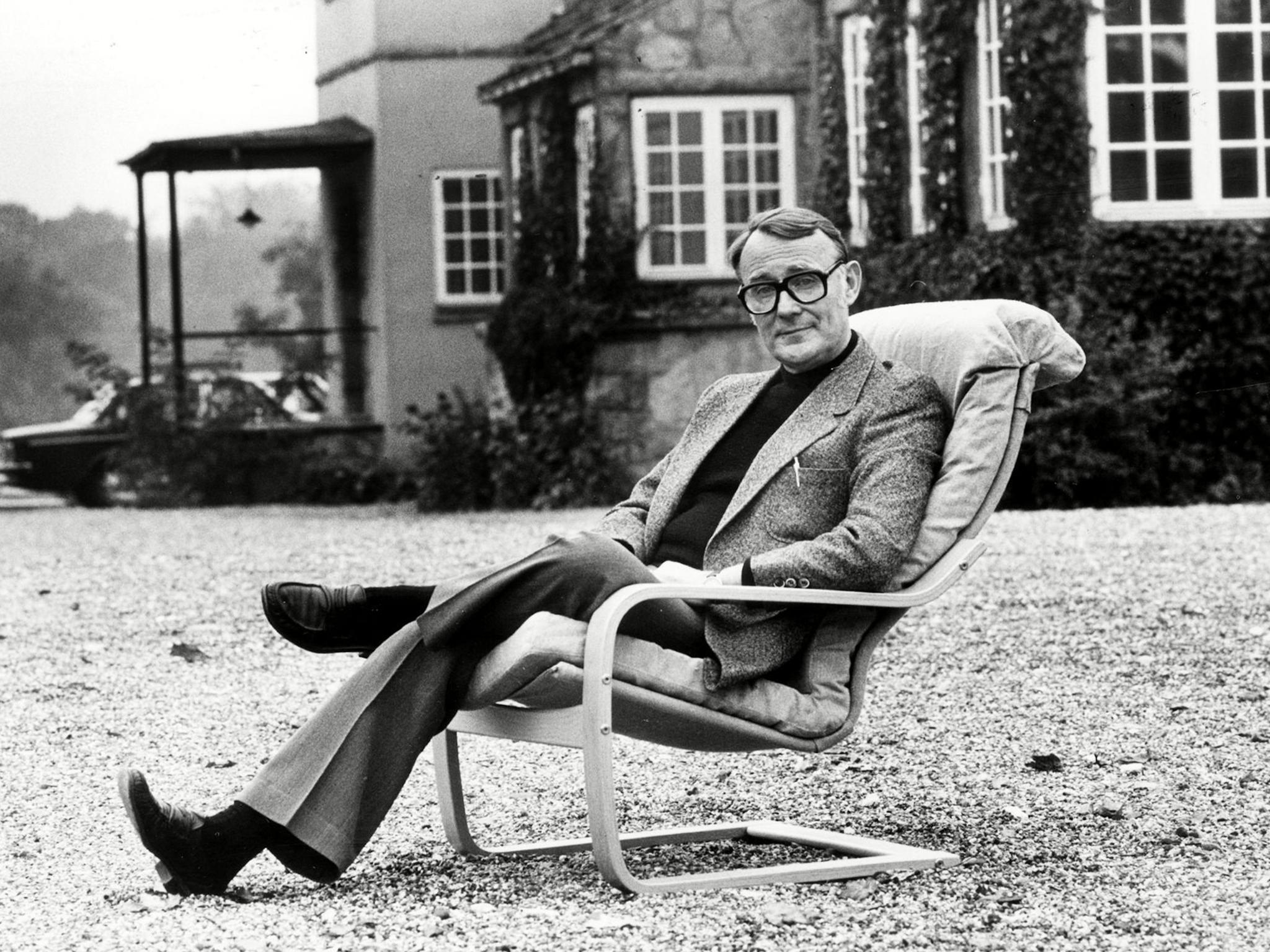

Ingvar Kamprad: Founder of Ikea who struggled to shake off Nazi skeletons in the cupboard

The billionaire, who was known for living frugally, transformed the way the world shops by innovating affordable flat-pack furniture in the 1950s

Ingvar Kamprad, the multi-billionaire founder of the Ikea furniture company, was born in 1926 near Almhult, in Smaland, a remote part of southern Sweden. His parents were Feodor, the son of German immigrants, and Berta, daughter of the owner of the biggest store in Almhult. Ingvar grew up on the farm that Feodor inherited from his parents in Elmtaryd, in the parish of Agunnaryd.

Kamprad’s lust for business manifested as early as five when he started selling boxes of matches to his neighbours at a profit. Thanks to the relative poverty of Smaland, he sensed early that price was the overriding factor in business. At 11, he struck his first big deal, involving garden seeds, the profits of which bought him a racing bike.

In 1943, aged 17, before going to the School of Commerce in Gothenburg, Kamprad set up his own mail order business selling imported pens. He called it Ikea: I for Ingvar, K for Kamprad, E for Elmtaryd and A for Agunnaryd.

After college he worked as a clerk at the Forest Owners’ Association, where he was allowed to sell files to his employer, the profits from this enterprise earning him more than his salary. Even during his national service with the Kronoberg Regiment in Vaxjo, the Colonel gave him permission for an additional night’s leave so that Kamprad could continue trading.

Although he had no background in furniture or great interest in design – indeed, Kamprad prided himself on “having no taste” – in 1948, he began to advertise in his mail order brochure, Ikea News, items of furniture designed to appeal principally to farmers and the rural poor. The first lines, all at unprecedentedly low prices, included an armless nursing chair called Ruth, a coffee table, a sofa bed and a chandelier, all made by local manufacturers in Almhult and sold at the lowest possible price. All Ikea pieces were given names, as Kamprad, who was dyslexic, had difficulty with numbers.

Within a few months, Kamprad bought his first shop in Almhult to house a permanent display of the goods on offer in his catalogue, so that customers could come and check the quality. Customers were offered coffee and cake in the shop and schnapps at the checkout. The shop was a big local success, and, complete with its more quirky Kamprad touches, remains the basis of the Ikea concept, although the company now has 355 stores in 29 countries.

Although Ikea only came to the UK in 1987, the UK rapidly became the company’s second biggest market after Germany.

Keeping costs down was always imperative to Kamprad. He would upbraid employees for leaving lights on, and on one occasion, shouted at an underling for throwing away some ends of string; the Ikea way was to knot them together for reuse. All Ikea executives, himself included, were to travel economy class and drive modest cars.

Even when he had a personal fortune estimated at $27bn (£19bn), Kamprad remained thrifty to the extent of searching his local market in Lausanne, Switzerland, where he lived in the latter part of his life, to save a few centimes on an item, and exasperated his second wife by asking for a discount at the local produce market.

Ikea’s early success in the 1950s riled the staid Swedish furniture business. The National Association of Furniture Dealers proposed a boycott of firms that supplied Kamprad’s business. Ikea and Kamprad personally were banned from trade fairs. He was sneaked into one fair, however, under a Wilton carpet in the back of a friend’s Volvo. Once inside, no one dared physically to throw him out. Soon, Kamprad circumnavigated the ban by starting up his own trade fair.

Kamprad’s greatest business breakthrough was flat-pack furniture. The idea for this came to him during the shoot for the 1953 catalogue. The photographer, grumbling about a table’s legs taking up too much space in a storage room, took them off and tucked them underneath the top. Kamprad, ever alert to money saving ideas, immediately saw how this could slash transport costs. Soon, customers were merrily performing half the production process themselves, lugging their own flatpacks down from racks, transporting them home and assembling them.

Kamprad married his first wife, Kerstin Wadling, a secretary at Swedish Radio, in 1950. The couple were unable to have children of their own and so adopted a little girl, Annika. The couple went through an acrimonious divorce in 1961, although they had resolved their differences by the time Kerstin died several years later, Kamprad’s later verdict was that he considered himself “a real s***”. In time, Kamprad would also be reconciled with his daughter.

After his first marriage ended, Kamprad took up the partying he had missed by working so hard. In the end, he was drinking so much that he sought medical help. Later, he would describe himself as an alcoholic who is “under control”.

On an Ikea staff trip to Italy, he met a school teacher, Margarethe Stennert, and they married in 1963, going on to have three sons, Peter, Jonas and Mathias. All the Kamprad sons are involved with Ikea, but keep a low profile.

In 1973, Kamprad built a store in Spreitenbach, Switzerland, determined as he was not only for Ikea to last beyond his lifetime, but also to be independent of any one country. Sweden’s harsh income tax regime had resulted in the bizarre situation of Kamprad being personally bankrupt from the early 1950s despite his thriving company. This was resolved in 1973 when Kamprad moved to Denmark and sold a foreign subsidiary company at an Skr8m (£721,000) profit. In 1978, the Kamprad family would move on to Lausanne, while some of the company headquarters were relocated to Holland.

Kamprad was a perfectionist. He would get up at 5.30am to ask delivery men their view on the company. He overcame his shyness to approach customers with the phrase “Hello, I work here. What did you think about us?” He was a nervous person who always arrived early for flights and felt ashamed if he was late for a meeting. When people were late for meetings with him he would pointedly greet them with, “Good afternoon”.

Kamprad was fond of saying that his life was a series of fiascos, and this was never more the case than in 1994 when a news story broke in the largest Swedish daily, Expressen, revealing that Kamprad had an exceedingly dubious Nazi background.

It was not merely that Kamprad’s father and grandmother were avowed, Mein Kampf-reading Hitler-worshippers, Ingvar himself had for almost two decades in the 1940s and 1950s been a supporter of two Swedish Nazi movements. As a teenager, he became involved with a Swedish fascist group called the Lindholmers, going on a youth camp and attending rallies where he discovered, he later recalled, a “new kind of fellowship that deep down I yearned for”. At the Combined Middle School in Osby, he formed a secret political party in the attic with several others and drew attention to himself by drawing swastikas on desks and in books. The headmaster had told Kamprad to “stop all that nonsense”.

Undeterred, in 1945 Kamprad became close to Per Engdahl, leader of what would become the neo-Swedish movement, another Nazi-style organisation. Engdahl was later invited to Kamprad’s first wedding, and gave a moving speech. Kamprad’s flirtation with these movements continued well into the 1950s, even though, ever the bottom-liner, he claimed he never actually gave them money.

When the press took interest in this aspect of his past, Kamprad described his actions as a “youth’s sickness” and sent an emotional letter of apology to every Ikea employee for “my latest fiasco”. Almost immediately, as if in contrition, Ikea announced plans to build a store in Israel, although this did not finally open until 2001.

Another of Kamprad’s regrets in life was that he felt he neglected his three sons while they were growing up because he was so involved with the business. According to one of his sons, Kamprad had been preparing for his death since 1976. In the same year, supposedly following requests from Ikea staff, he wrote a strange, homily-laden booklet called A Furniture Dealer’s Testament, which outlined the nine tenets of Ikea that are still followed today.

Kamprad liked to think he treated the staff of Ikea as an extended family. His Christmas message always started: “Dear Ikea family, A great hug to you all...”. Staff undergo training called “The Ikea Way Programme” and are kept in touch by a regular newsletter. An ex-senior Ikea executive once described the company at its worst as being “like a sect”.

During his life, Kamprad took precautions to ensure that his death would not interfere with the smooth running of the business. A precise plan was set for the 100 years following his death, which dictates who is to do what.

Kamprad, with his eye for detail and precision, even specified where he wanted to be buried – in a birch grove in Smaland, where Ikea began.

Ingvar Kamprad, businessman, born 30 March 1926, died 27 January 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks