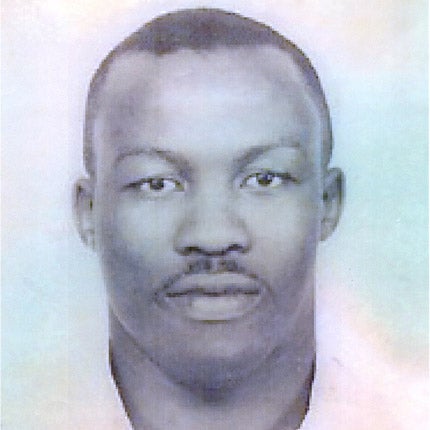

Isaiah Stein: Activist who played a significant role in the overthrowing of apartheid

The first figure in the struggle against apartheid to be placed under 24-hour house arrest, Isaiah Stein was a freedom-fighter perhaps better known as the father of the footballers Edwin Stein (Luton Town), Brian Stein (Luton Town and England) and Mark Stein (Chelsea).

Born in Durban in 1931 to parents of mixed ethnicity – and with a father who was a property developer and pastor – little is known of his upbringing save the fact that as a late teenager, and following his parents' death, he moved to live with his brother in Cape Town's famously mixed District Six. It was 1948, the year the National Party won power.

He shot to prominence as a boxer under the name of Boston Tababy, and was arrested on the first of many occasions for fighting a white man. He seems to have worked for a Cape Town Jewish family, and been adopted by them and taken their surname, as was common at the time for. But the affection Stein clearly held for a couple who had embraced him as employee and as friend, together with the risky range of his emerging political activism, meant that he never talked about the name change, perhaps for fear of exposing them to danger.

Renowned for his hard-working nature, and commitment to anyone in need, Stein inherited his father's property-developing abilities. Following his forcible removal from District Six to the "coloured" Athlone area – he was among the first to be removed in this way under the Group Areas Act – he swiftly built homes which ensured some financial stability and gave him a base for his community activism. They also attracted the attention of his first wife, Lillian Jacobs, who had been evicted from her home. Her friendship with Stein blossomed into a marriage which saw them have eight children of their own and adopt a daughter.

Protests were growing against the pass laws, and as the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960 alerted the world to the viciousness of the regime so Stein became chief organiser for the Coloured People's Congress. He facilitated meetings, protests and marches across the Western Cape, as well as disruptive activity, safe passage for banned persons and material assistance for comrades and their families, as well as liaising with leaders like Nelson Mandela.

In and out of prison and frequently tortured by the police – the physical scars on his legs were visible to the end of his life – Stein and his wife were on one occasion dragged naked from their home in the middle of the night. They were both tortured severely and Stein only ensured his wife's release when he undertook an 18-day hunger strike.

Following this episode in 1964, Stein was put under 24-hour house arrest as part of a nationwide crack-down that sent Nelson Mandela to Robben Island. Stein decided reluctantly that an exit pass to England was the only way forward. He left Cape Town for Southampton, bereft of his citizenship, on 1 February 1968, with his wife and all but one of their children, Julia, who remained in Cape Town with relatives.

Met by the Bishop of Stepney Trevor Huddleston, who provided them with furniture – Stein treasured a dining table all his life – and assisted with housing by the other great priest-opponent of apartheid at the time, Canon John Collins of St Paul's Cathedral, Stein began working as a distribution manager for Heinemans, the leading publisher of African authors.

The contrast between the two countries can hardly have been greater, though the issue of racism was certainly shared, as Enoch Powell's "Rivers of blood" speech a few months after their arrival reminded them. Stein was soon using his background as boxer and community organiser, and his acute political antennae, to energise the sporting boycott campaigns of the late 1960s and early '70s. Albie Sachs, former judge of the post-apartheid Constitutional Court, remembers Stein's tenacity, recalling them standing with Denis Brutus as they shouted themselves hoarse at Twickenham in 1973 when the Springboks visited. It was the team's last match until the 1990s.

Stein was a natural choice for a key role in the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee which had been formed in 1962 and was by the late 1960s being run from London. Stein played a key role as SAN-ROC worked to ensure that apartheid South Africa was removed from the Olympic movement. Following their expulsion in 1970, Stein represented SAN-ROC at meetings with the United Nations' Special Committee Against Apartheid, the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa and International Sports Federations. In this regard he attended the Olympic Games in 1976. But activism on the world stage never prevented him from achieving the grassroots connectedness by which he had become such an irritant to the apartheid regime and a well-loved figure to the comrades of the struggle. He drilled into his children – all of whom achieved much in sporting, educational and youth-work contexts – that justice was the foundation of everything. This invariably meant sleeping with blankets on the floor as visiting South African struggle figures took their beds.

Though his first marriage was dissolved, Stein's respect for the wife who had been tortured as a result of his political activities was lifelong.

As the struggle moved to its conclusion, a chance telephone meeting was to bring Stein personal change that would shape the latter part of his life.

A friend of his visiting Cape Town, met four women, and joked that a South African-in-exile might be looking for a new partner. Three of the women brushed the joke aside but one of them saw it as a challenge. Stein was phoned and instantly something clicked when he and Deborah Pearl Julius began to speak. A two-year correspondence led to an air ticket for the prospective Mrs Stein, and a 21-year marriage.

Stein shared the joy of the transformation that followed the end of apartheid, and revelled in his vote and returned citizenship; he revisited the scene of his Cape Town activism several times. He submitted the story of the human rights violations he had suffered to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, but the onset of dementia, began to diminish his sense of identity as he became more reliant on the devoted care of his wife and family.

Before the dementia became acute Stein would talk a little about his life. But not much. The necessary secrecy of the freedom fighter together with his innate modesty prevented him from focussing attention on his achievements. He was forward-looking, passionate to realise the idealism that had driven him. But he was a wise man, who knew that when idealism meets reality disappointment can set in.

A staunch supporter of the Labour Party he often joked in later years that he was no longer a socialist – there didn't seem to be so many of those around, he said – just a socialite. And he commented when reflecting on certain aspects of the new South Africa that if he were to write an autobiography it would be called All for Nothing. But to that title a question mark would certainly have been appended – and the widely read Stein was meticulous about such things. For he knew that only by critiquing the new South Africa and its governing class would another generation be encouraged to find new energy for the ongoing struggle for justice, equality and freedom. Isaiah Stein gave his life for that struggle.

Isaiah Stein, political activist: born Durban 26 October 1931; twice married (eight son, two daughters); died London 20 January 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks