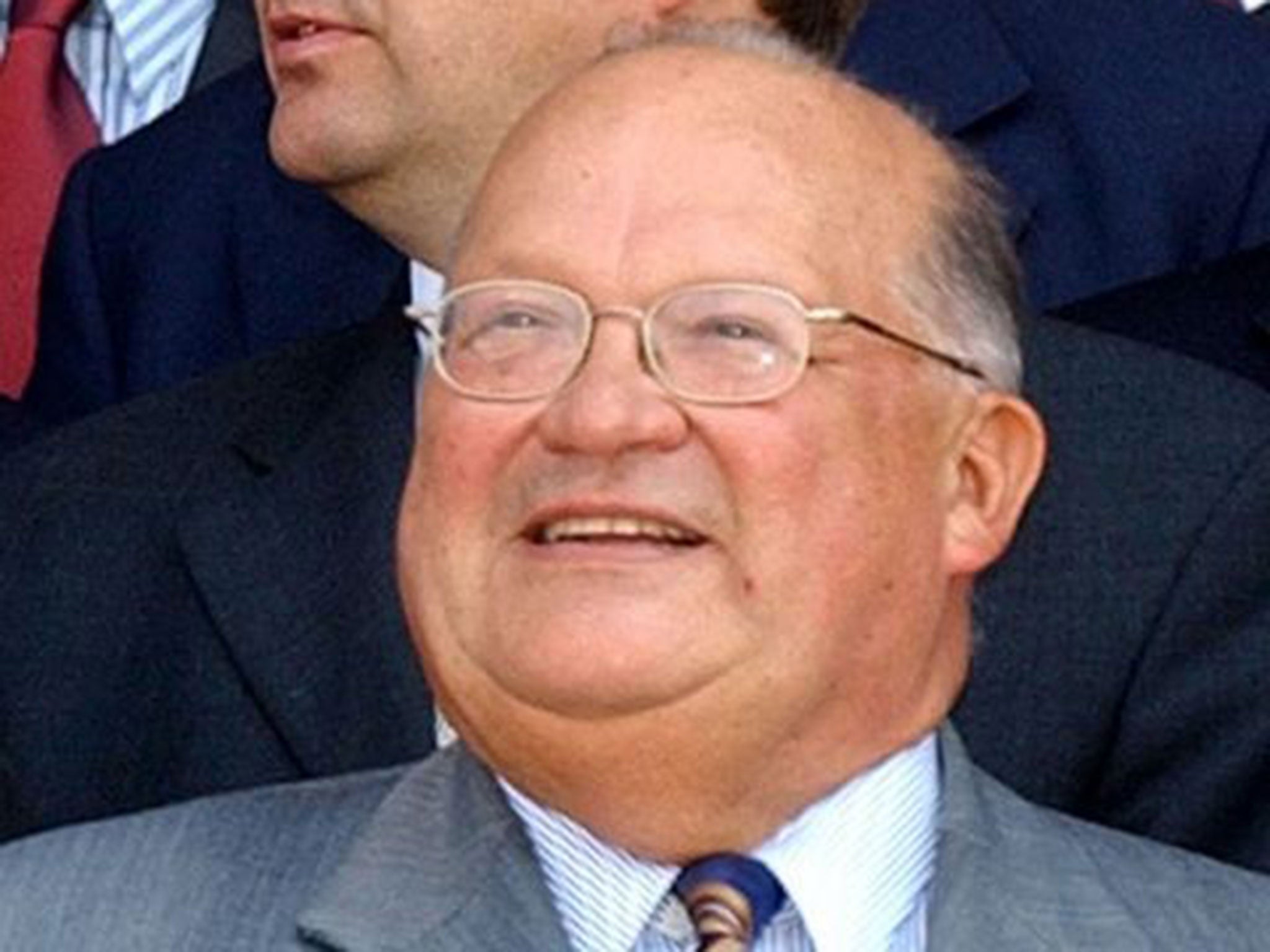

Jean-Luc Dehaene obituary: Politician who fought hard to keep Belgium together and went on to lead Uefa’s Financial Fair Play initiative

His withdrawal of Belgian troops from Rwanda opened the door to genocide; he said he had no regrets

As Prime Minister of Belgium, Jean-Luc Dehaene worked as hard to keep his divided nation together as he did to promote European unity. An avid football fan, he also led the investigation team of the Financial Fair Play campaign conducted by European football’s governing body, Uefa, which is seeking to control excessive spending by the continent’s leading clubs. One of his last acts was to propose to the free-spending Manchester City a £50 million fine and a cut in their squad.

Dehaene excelled in the minutiae of legislative work, which made him the master of complicated compromise agreements that few outside the upper echelons of politics fully grasped. He was referred to as “the plumber” because he was able to fix the seemingly unfixable, as well as “the minesweeper”, although opponents called him “the bulldozer”.

He was portly and unapologetic for his gruff demeanour, his best-known quote to the media being “no comment”, often followed by a menacing glare. Many politicians, though, loved his style. “Very direct and straightforward,” said the Belgian Liberal Guy Verhofstadt, who succeeded him as Prime Minister. “Everyone loved to work with him.”

He was born in Montpellier in the south of France when his parents, who lived in Bruges, were fleeing the German advance. He attended a Jesuit school, then went on to the University de Namur and the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven; he also joined the Olivaint Conference, an organisation which seeks to prepare students for public life.

His political career began when he joined the General Christian Workers’ Union, which was linked to the Christian People’s Party. In 1981 he was made Minister of Social Affairs and Institutional Reforms, then in 1988 became Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Communications and Institutional Reforms.

He began the first of his two terms as Prime Minister in 1992, at the head of a coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats. He pushed through constitutional changes to turn a nation of 6.5 million Dutch-speakers and 4.5 million French-speakers into a federal state with sizable amounts of regional autonomy but with enough in common to remain just about united, if all but ungovernable. He made sure Belgium became a founding member of the eurozone despite a massive national debt.

He hoped to succeed Jacques Delors as president of the EU in 1994 but the appointment was vetoed by John Major, who was battling the eurosceptics in the Conservative Party and saw him as too much of a federalist; the job went instead to the Luxembourgeois Jacques Santer, who turned out to be something of a federalist himself. Dehaene arguably never forgave the British: on his desk was a photograph of himself and Margaret Thatcher sitting together at a celebration of the opening of the Channel Tunnel. Dehaene is fast asleep.

In 1993 he had been praised for the way Belgium steered the EU presidency through the Maastricht Treaty and the Gatt world trade crises, but his second term as prime minister was troubled. In 1994 he withdrew Belgian troops from Rwanda, a decision which effectively opened the door for the genocide of Tutsis by Hutus. He said he had no regrets.

Perhaps the worst crisis for him was the Dutroux scandal, when the government nearly fell after it was revealed that the mass murderer Marc Dutroux, a builder from Charleroi, had been under surveillance. Three searches of his house had failed to detect two girls he had kidnapped, who starved to death.

There was also a series of corruption scandals, and then shortly before the 1999 election it was revealed that carcinogenic dioxins had been found in Belgian animal feed, leading to bans around the world on importing food from the country. Defeated in the election, Dehaene turned his focus to Europe and played a key role in brokering an EU constitution. After referendums in France and the Netherlands rejected it, many parts of the plan were taken up by the Treaty of Lisbon that currently sets EU policy. “It made me proud,” he said.

The EU President Herman Van Rompuy was a close party colleague throughout his career and only emerged from Dehaene’s shadow after he took on the biggest job in the EU in 2009. “Only 10 days ago, I told him, ‘If I have been able to achieve something in Europe, it is because I learned it from you,’” Van Rompuy said.

Combining his love of football with his knowledge of finances – he was a fan of Club Brugge – Dehaene took the lead in Uefa’s Financial Fair Play campaign, which seeks to prevent rich owners pumping in funds to their clubs, which then operate with massive losses. “He was a statesman and a man of conviction,” the Uefa President Michel Platini said. “We are all going to miss his passion, simplicity, irreproachable professionalism and great sense of duty.”

Belgium has lost “an exceptional statesman,” the country’s current Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo said. “Jean-Luc was a special companion.” Dehaene had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer earlier this year but died in France following a fall.

Jean Luc Joseph Marie Dehaene, politician: born Montpellier 7 August 1940; married Celie Verbeke (four children); died Quimper, France 15 May 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks