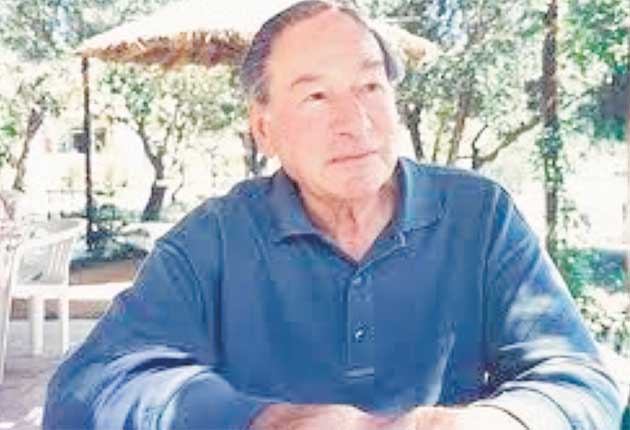

John Ehrman: Historian and literary benefactor celebrated for his magisterial life of Pitt the Younger

If asked what he did, John Ehrman, always modest, would reply that he was a historian. Others who knew him better would say "the historian"; looking back now over a life nearly a century long, "the great historian" seems nearer the mark. Others have practised history, written long books, studied the detail with minute care, taken a large theme and enlarged it, but was anyone else so completely devoted to the recording of historic fact and setting it out in clear prose, without bias or rhetoric? Beside this was a life of public duty, spent without demur or ostentation, even though at times it distracted him from his larger task. That all this was accomplished during a lifetime more than half of it marred by partial disability makes his achievement all the greater.

John Ehrman was born in London to Albert and Rina Ehrman. His father was a diamond broker, specialising in industrial diamonds; he knew their strategic importance in the war that he foresaw more clearly than most, and effectively withheld supplies to the fascist powers (both father and mother each gave the RAF a Spitfire during the war). He was also a discriminating collector of old books and manuscripts, specialising in the documents of the book trade and its history. He also kept a yacht at Buckler's Hard, near Beaulieu, and was an expert navigator.

Educated at Charterhouse, John Ehrman took naturally to history and early evinced a special taste for the "long" 18th century, the period from the "Glorious Revolution" to Waterloo. He went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, in September 1938. A year later he was in the Navy and spent the war in corvettes, containing the Italian fleet in the Mediterranean and protecting convoys in the North Atlantic. He returned to Trinity in 1945 and was elected to a fellowship in 1947. His capacity for detailed research and narrative skill caught the attention of the Master, George Macaulay Trevelyan, but it was his tutor, Sir James Butler, who diverted him from the navy in Pepys's time, his chosen topic, to work in the Cabinet Office on the official history of the Second World War, of which Butler was the editor.

This was to engage him for the best part of eight years. He found time to publish The Navy in the War of William III, 1689-97 (1953), but it was the two substantial volumes of the war history published three years later, Grand Strategy, 1943-45 that made his name and demonstrated his ability to draw out the main strands that constituted the war's strategic direction. In 1953 he also wrote the official account of the British part of the history of the development of the atomic bomb and the decision to use it, which was printed by the Cabinet Office but kept secret for 40 years until it was declassified and made available in the Public Record Office. His experience of the inner workings of government led to Cabinet Government and War, 1890-1940 (1958).

By now he had returned to Cambridge as Lees Knowles Lecturer, 1957-58, and he began the long years of research into the life and times of William Pitt the Younger that was and will be his lasting claim to fame. The first product of it was The British Government and commercial negotiations with Europe, 1783-93 (1962), which covered the years when Pitt was a very young Chancellor of the Exchequer.

In 1960 Ehrman caught polio and recovery was slow and perilous. His determination and the support of his wife Susan saw him through it, but he had to wear an iron leg-brace for the rest of his life. This did not stop him from becoming Honorary Treasurer of the Friends of National Libraries (1960-77), a task that provided a convenient platform from which to undertake another task of great public benefit, the dispersal of his father's collection after his death in 1969. This was following family tradition: his father had regularly given his favourite libraries a present on his own birthday every year.

After taking extensive advice, Ehrman decided in 1976 to give the British Library 23 early printed books, 13 of them the only known copies, to the Bodleian Library, Oxford, the book-binding collection; and to Cambridge University Library another 20 early printed books, and the collection of book-trade documents, catalogues, type-specimens, and the like. Fifty books from the early imprint collection were given to suitable libraries, and the rest sold at Sotheby's. It was an informed and well-executed dispersal that greatly strengthened its beneficiaries.

He became a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1958 and of the British Academy in 1970. He was Vice-President of the Navy Records Society, 1968-70 and 1974-76, a trustee of the National Portrait Gallery, 1971-85, member of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art, 1970-76, and of the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, 1973-94. He was Chairman of the British Library Advisory Committee, 1979-84, and – a special enthusiasm – of the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust, 1989-94. As well as useful advice in and outside meetings, Ehrman often added practical and financial support to his work for all these good causes.

Time for them was spared (stolen, he would say) from his long work on the life of Pitt. He gently refused other distractions, the professorial chairs that he was offered and other honours, apart from the James Ford Special Lectureship at Oxford in 1996-97. The first volume of The Younger Pitt, The Years of Acclaim (1759-89) came out in 1969, followed 13 years later by the second, The Reluctant Transition (1790-96), and then by the third, The Consuming Struggle (1796-1806), which in 1996 won the Yorkshire Post Book of the Year award.

There is a natural empathy between biographer and subject. Pitt was a master of detail; so was Ehrman. Both knew what it was to be isolated by a great driving purpose. They shared a quiet sense of humour, Ehrman's like Gibbon's in his footnotes. Pitt's speeches were admired by Churchill; Ehrman's prose was worthy of his subject. His book is and will remain one of the great monuments of scholarship of our time.

Nicolas Barker

John Patrick William Ehrman, historian: born London 17 March 1920; married 1948 Susan Blake (four sons); died Taynton, Oxfordshire 15 June 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments