Lord Newton of Braintree: Politician admired for hisdecency and reforming zeal

Although his political career came to a disappointing end with his defeat in the 1997 general election and his failure to secure selection for the European Parliamentary elections in 1999, Tony Newton continued to make a substantial contribution to public life, not least in the often underrated task of chairing a major mental health provider, the North Essex NHS Trust from 1997 to 2001, and then as Chairman of the Brompton and Harefield NHS Trust from 2001 until 2008.

Since 2009 he had chaired the Suffolk NHS Mental Health Trust. More important still was the part he played as Chairman of the Council of Tribunals from 1999. He oversaw its transformation into the Administrative Justice Tribunals Council and became the first chairman of the new body from 2007 until 2009. He played a crucial part in reforms which made tribunals more central to the machinery of justice and he earned the respect of judges, lawyers and pressure groups for his genuine championship of individuals who had cause to believe that the state had not behaved towards them as it should. This largely unsung pursuit of public service when well into his seventies tells us much of the way that he put service to others at the heart of his life. As John Major remarked, only half in jest, "if a tramp stole his suit, Tony would rush after him with a matching shirt."

Newton spent almost 18 years in government, initially as a whip, but on promotion to Under Secretary to the Department of Health and Social Security in 1982 he found his metier and won respect for his competence and caring approach. This was not then an area in which a Conservative found it easy to build a reputation with No 10, but in 1984 Mrs Thatcher made him Minister for Social Security and two years later, Minister for Health and Chairman of the NHS management board.

It was a fitting reward for the part he had played in drafting the Social Security Act, which created Family Credit and replaced supplementary benefit with income support. There was a growing realisation that the NHS's management structure needed an overhaul and that waiting lists were too long However, Newton's priority had to be Aids and he favoured spelling out the facts with brutal starkness. It also fell to him, after the 1987 election, to deal with the Cleveland child abuse scandal. He was to win golden opinions for the sensitive way in which he handled an issue in which paediatricians had clearly misled themselves about the extent of the problem. He set up the Butler-Sloss enquiry and put in place skilled local task forces to implement the lessons learnt.

The Department faced an aggressive Labour campaign highlighting chronic underfunding in the NHS; Newton's Secretary of State, John Moore, had agreed a low settlement for 1987-88 and the media turned with zest to expose stories of operations cancelled and a whole series of other deficiencies. Moore buckled under the strain and contracted pneumonia. Newton stepped into the breach, launching the White Paper on primary care on which Moore had been working, finding an additional £100m for hard-pressed health authorities and £700m for the following year.

He had to cope with Conservative unease when Labour found an easy target, the decision to be rid of free eye and dental checks. Thatcher recognised the ability with which he fought his corner when she made him a Privy Councillor, but she also recognised that it was no longer enough to hold the line. NHS reform was inevitable and a review was set in train, but the Prime Minister concluded that the DHSS was too much for one person. In July 1988, the department was split, with Moore retaining Social Security, while Health went to the more resilient Ken Clarke. Newton was forced to leave a job he loved to take over Clarke's responsibilities at the DTI.

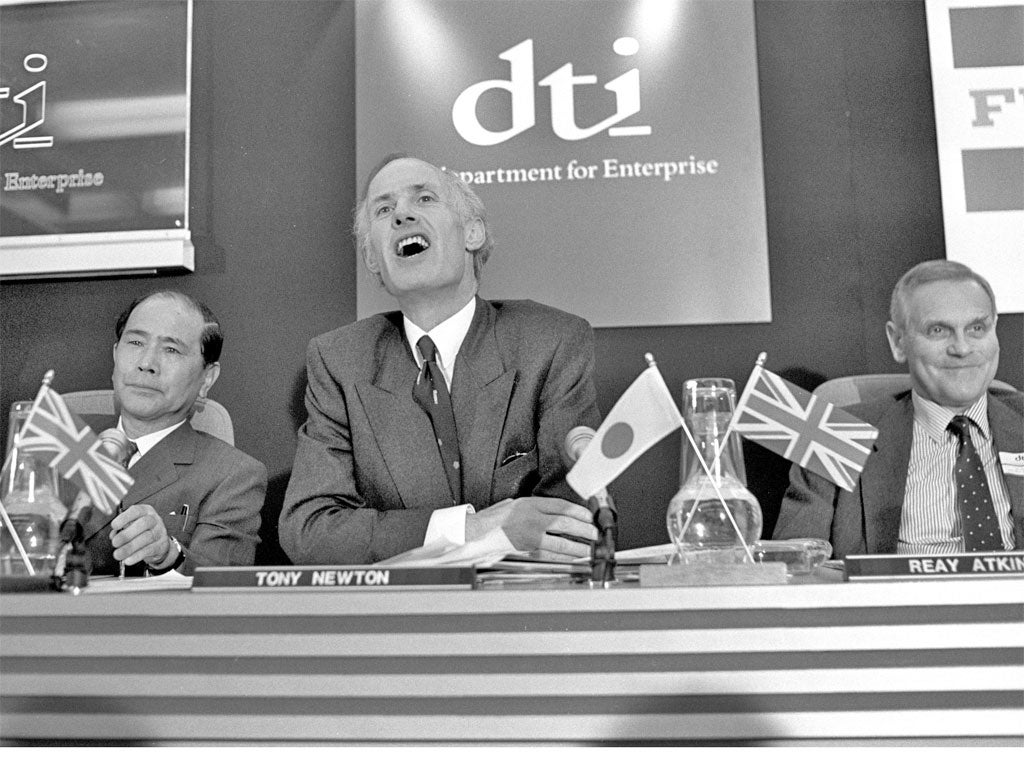

The move was not a success even though it brought a well-earned place in the Cabinet. Lord Young had treated Clarke as a partner; he found it difficult to see the quieter Newton the same way, and the latter was embarrassed at having to defend his chief over his handling of the Fayed takeover of Harrods. It was a relief to both men when a year later Moore bowed out and Newton took his place at Social Security.

It was not an easy time as spending rose to cope with the recession. Newton had to cope with difficult spending rounds in which he was asked to cut the social security budget. Although defeated over an attempt to raise child benefit, he was able to set in train a review of benefits for the disabled, which had long been one of his interests. Defeat in the European Court forced him to equalise the retirement age for men and women and defeat in the Commons undid his efforts to make people pay more of the costs of their place in a retirement home.

Honouring Thatcher's pledge to ensure that absentee fathers supported their children, he was responsible for the Child Support Agency, though not for the bureaucratic nightmare which developed. When John Major took over as Prime Minister, he created the Benefits Agency. The two had a lasting alliance from their service together at the DHSS. Further problems developed, not least when it transpired that the late Robert Maxwell had raided his companies' pension funds. Newton put legislation in place to minimise the future risk of such raids and he was also responsible for a useful scheme by which a homeowner at risk of repossession could become a tenant in his own home.

Seen as one of Major's "four musketeers" in the run-up to the 1992 general election victory, he was made Leader of the House and chaired a number of important Cabinet Committees. But Major's small majority was unruly and eurosceptic, determined to bring down the Government's legislation to implement the Maastricht Treaty. In the end after consulting his colleagues, he was forced to threaten the rebels with removal of the whip in November 1994. Eight took him at his word, and Newton, characteristically pragmatic, bent his talents for conciliation to the task of bringing them back into the fold.

He was not at his best in handling the "Cash for Questions" affair. He ensured the Members concerned were suspended and launched an inquiry, but his insistence that it sat in private was met with a Labour walk-out and criticism from a press determined to portray Major's government as sleazy. Newton knew this was not the case and thought the Commons would suffer if MPs were compelled to reveal outside interests. He was prescient in fearing the professionalisation of politics, but the compromise he forced was defeated on a free vote in the Commons.

Inside the government he wielded considerable influence, and was one of those who prevented Michael Heseltine from going ahead with Post Office privatisation. He was far less successful, though, in querying what he saw as the dangers to civil liberties in Michael Howard's Criminal Justice Bill. He continued to be close to Major and was one of the handful of ministers consulted about his decision to seek re-election as party leader in 1995. He thought the move would work and did a great deal to ensure that it was seen as triumph.

Major had encouraged him to play the role Willie Whitelaw had played in Thatcher's government a decade earlier, but Newton never acquired the authority Whitelaw had enjoyed, and as the election neared, others became more dominant in Major's counsels.

Defeat in 1997 was a deep disappointment and somewhat unexpected, but he probably found more satisfaction in the numerous tasks he undertook from a base in the Lords than he would have done in opposition in the Commons.

Tony Newton was essentially a decent and caring Conservative in the "Rab" Butler mould. He had a warm personality and considerable charm; he was completely trustworthy. Major confided in him at the time of his affair with Edwina Currie and Newton preserved the confidence. Although he was often nervous before making a speech and smoked incessantly while waiting to make his way to the floor of the Commons or the platform – Edwina Currie tried in vain to break him of the habit – once on his feet he was lucid and persuasive, the complete master of his brief. A slightly careworn appearance belied an inner resilience and an ability to work hard and fast. He was highly intelligent, well versed in economics, and his quiet voice often prevailed in committee because he spoke such obvious common sense. He died after a long illness, but one which was never allowed to blunt his determination to continue his immense contribution to public life.

Antony Newton was born in Harwich, the son of a builders merchant, and educated at a Quaker independent school, the Friend's School in Saffron Walden, where he shone in the classroom and at sports. At Trinity College, Oxford he read PPE but much of his energy went into politics. He was president of the Oxford University Conservative Association in 1958 and within a year president of the Oxford Union; he also became a vice chairman of the Federation of Conservative Students. Like many of his contemporaries he joined the Bow Group, becoming Secretary and Research Secretary, and the Coningsby Club, chairing it in 1965-66.

Keen to play a part in policy-making and with one eye on the Commons, he joined the Conservative Research Department and from 1965-70 headed its economic section. After an unsuccessful attempt to enter the Commons at Sheffield Brightside, he returned to Old Queen Street as Assistant Director, and was selected to fight Braintree at the February 1974 election. He won the new seat by 2,001 votes, saw his majority almost halved the following October, but built it up to 17,994 in 1992. After boundary changes, which had a greater effect on the seat than most observers recognised, he fell victim to the huge Labour swing in 1997, and accepted a life peerage as Baron Newton of Braintree.

Among his other appointments, Newton took the chair of the Standing Committee on Drug Abuse, and the review committee on the Anti Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001. As Chairman of the Hansard Society's Commission on Parliamentary Scrutiny (1999-2001) he noted how parliament was being left behind by changes in the constitution, government and society, and set out reforms. More recently he chaired The Buncefield Major Incident Investigation Board. It cannot be easily equalled as a record of public service and every job he undertook was well done.

John Barnes

Antony Harold Newton, politician and economist: born Harwich 29 August 1937; MP (C) Braintree 1974–97; cr 1997 Life Peer; married 1962 Janet Huxley (divorced 1986; two daughters), 1986 Patricia Gilthorpe (one stepson, two stepdaughters); died 25 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments