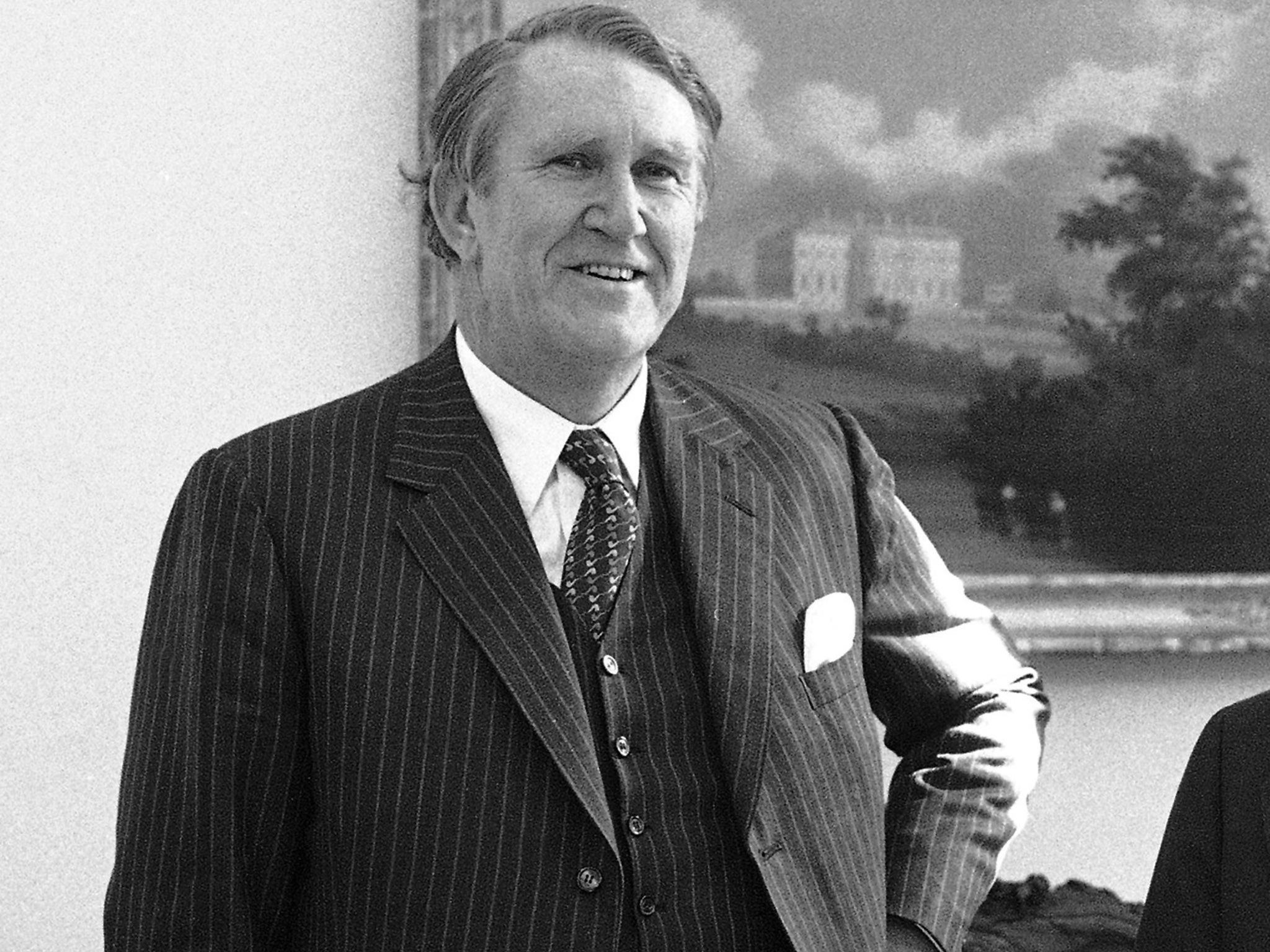

Malcolm Fraser: Politician who became Australia's Prime Minister when the Governor-General controversially sacked Gough Whitlam

Malcolm Fraser was catapulted to power in Australia by a constitutional crisis that left the nation bitterly divided. With his cultivated old-money accent and a stony countenance that cartoonists lampooned as an Easter Island statue, many mistook him for an archetypal creature of the right.

But he later became a vocal critic of conservative politics in Australia and a thorn in the side of the centre-right Liberal Party that he once led, and he eventually resigned in disgust in 2010 when the party elected Tony Abbott as its leader, saying, “The party is no longer a liberal party but a conservative party.”

Fraser became the unelected leader of an unsuspecting nation in 1975 when the Governor-General John Kerr took the unprecedented step of dismissing the chaotic, frenetically reformist government of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. Fraser, leader of the opposition, triggered the crisis by delaying the government’s budget bills, hoping to force an early election that he was confident of winning.

After several months of political deadlock Kerr stepped in and removed Whitlam. It was a development that most Australians had not thought possible; they were outraged that the Queen’s Australian representative would dare to get rid of a democratically elected government. An indignant Whitlam branded Fraser as “Kerr’s cur” and urged voters to “maintain the rage” at the ballot box.

Shortly after Fraser had called the election a letter bomb was sent to him, but it was intercepted and defused before it reached him. Despite Whitlam’s angry words, a month after taking power as a caretaker government Fraser’s conservative coalition won a clear victory over Whitlam’s centre-left Labor Party.

At first he maintained Whitlam’s levels of tax and spending, but began to rein in inflation, which had soared under Whitlam, partly thanks to his so-called “Razor Gang” which implemented drastic budget cuts. His refusal to implement the right-wing programme his enemies had predicted alienated some of his followers, but Fraser went on to win another two three-year terms.

His achievements included legislation that gave land back to Aborigines in the Northern Territory, an outcome he always gave credit to Whitlam for initiating – although his childhood friendship with an Aboriginal girl may have helped. He strove to transform Australia into a multicultural society and was a vocal opponent of apartheid, refusing permission for the aircraft carrying the Springbok rugby team to refuel on Australian territory en route to their controversial 1981 tour of New Zealand.

He also strongly opposed white minority rule in Rhodesia, and during the 1979 Commonwealth Conference he helped convince Margaret Thatcher to withhold recognition of the Zimbabwe-Rhodesia government, which she had earlier promised to recognise.

He opened Australia’s doors to tens of thousands of refugees following the Vietnam war, created Australia’s multicultural broadcaster Special Broadcasting Service and was the first chairman of the humanitarian organisation CARE Australia.

With Australia’s postwar economic boom stalling in the early 1970s, Fraser’s government battled rising inflation and growing unemployment. A saying he would occasionally use came to epitomise for many Australians his government’s philosophy: “Life wasn’t meant to be easy.” He later explained that the line was a partial quotation from George Bernard Shaw: “Life is not meant to be easy, my child. But take courage. It can be delightful.”

Fraser was born in the wealthy suburb of Toorak in Melbourne in 1930. He was educated at the exclusive Melbourne Grammar School and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he read PPE before reluctantly returning to farming in Victoria. He was Australia’s youngest MP when he entered parliament in 1955, and in 1966 he became Army Minister, overseeing the unpopular Vietnam conscription programme. He became leader of his party in 1974.

But his legitimacy as a leader never recovered from the controversy over how he got there. The “Kerr’s cur” tag lingered in the nation’s memory for decades, although years after his and Whitlam’s parliamentary careers ended the two political foes became friends. They shared a disappointment that their rival parties had both shifted to the right on issues including the treatment and detention of asylum seekers. Whitlam died last October at the age of 98.

During the Vietnam war, Australian troops had fought alongside the US, Australia’s most important strategic ally and a treaty partner since 1951. Fraser’s political transformation was underscored last year when he published a scathing account of the US-Australian alliance entitled Dangerous Allies, described by some reviewers as radical. The book, which describes drones as “weapons of terrorists”, argued that the alliance had become a liability for Australia since the end of the Cold War and risked dragging the country into an unwinnable war against China.

One of his last political acts was revealing: in a television advertisement he came out in support of the Australian Green Party Senator, Sarah Hanson-Young.

John Malcolm Fraser, politician and human rights activist: born Toorak, Melbourne 21 May 1930; Prime Minister of Australia 1975–83; married 1956 Tamara (two daughters, two sons); died 20 March 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments