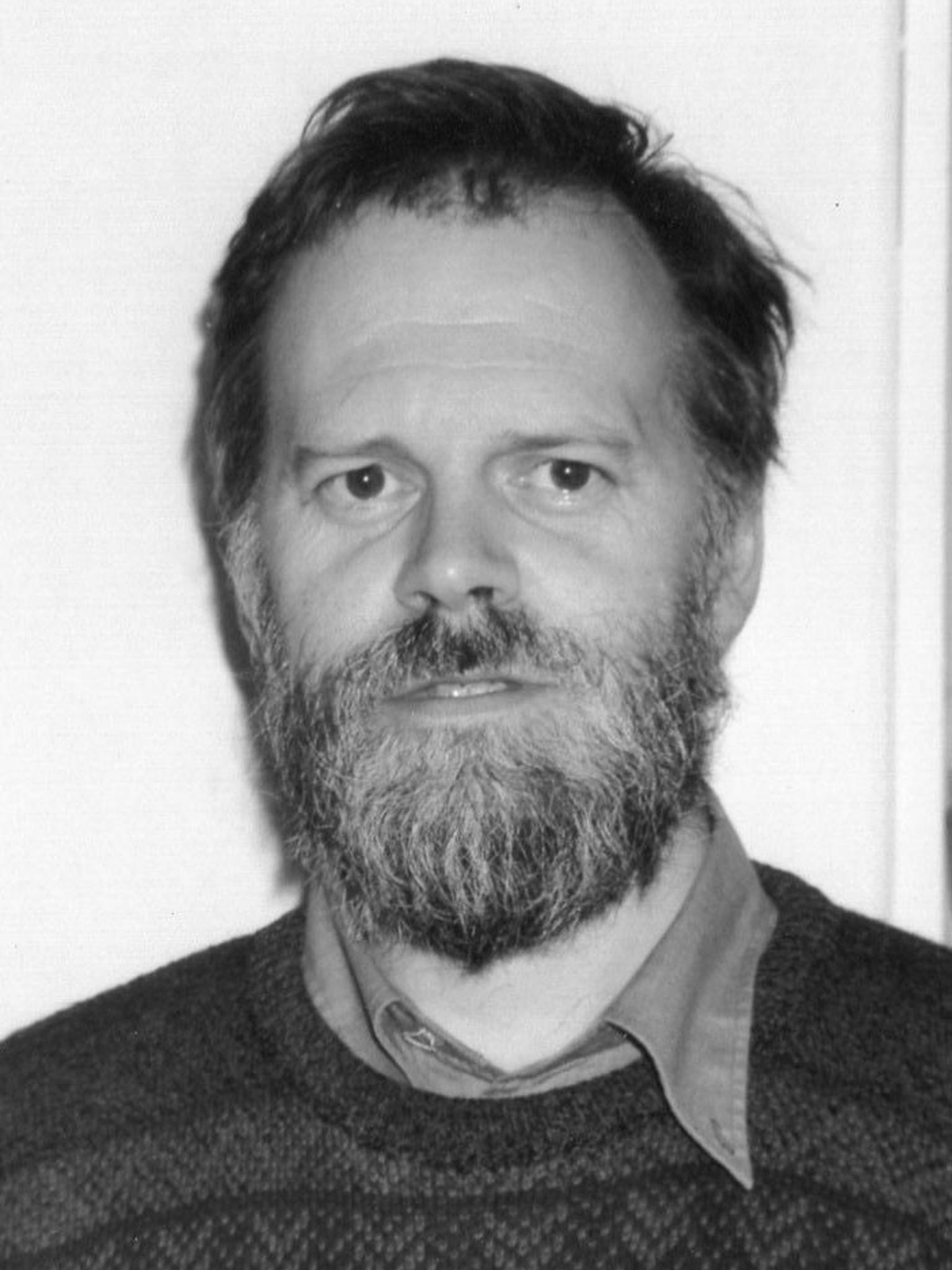

Malcolm MacDonald: Doyen of classical music writers whose prolific output brought many contemporary composers to wider attention

Malcolm MacDonald was one of the most gifted writers on classical music that the English language has produced, a worthy successor to Shaw, Newman and Tovey. MacDonald had a way of putting his finger on what brought a piece of music to life: when you read one of his descriptive analyses, you felt you almost knew the piece, however obscure it might be.

Much of the music he wrote about was unknown, and many composers would be today far less familiar without his writing. Between 1974 and 1983 a three-volume commentary on the 32 symphonies of Havergal Brian appeared, and MacDonald remained the unimpeachable authority on Brian's music, as he was on the music of John Foulds, a Mancunian who moved to India in the 1930s and was then forgotten; the revival of interest in Foulds' music began with MacDonald's 1975 life-and-works.

Other books examined Brahms, Schoenberg and Varèse and his friend and compatriot, the Scottish composer Ronald Stevenson; his contributions to symposia embrace a catholic range of further composers. He produced catalogues of the works of Dallapiccola, Doráti and Shostakovich, and his articles and reviews cast the net even wider. His knowledge was profound: I frequently commissioned him to write booklet essays for Toccata Classics, the CD label I run; whoever the composer, he would turn out a text with the ring of authority and authenticity.

In some instances he knew the music backwards – literally. When Morris Kahn, publisher of MacDonald's Brian monographs, received the photographic plates for the music illustrations (written out in MacDonald's calligraphic hand) for the first volume, he groaned: the plates, almost 150 in number, were unnumbered. To his astonishment, MacDonald, reading them backwards and from negative images, identified them all instantly.

MacDonald was born in Nairn and spent his first five years there, before his family moved to Edinburgh to join his father, Donald MacDonald, head of geography at the Royal High School and a gifted jazz pianist. His mother, Christina (née Lamont), was a primary-school teacher. His first encounters with classical music came courtesy of the family pianola, at which he would sit, vigorously pumping the pedals; he credited the perforations of the piano rolls for allowing him to "see" music as he heard it.

The school record society expanded his horizons, and he realised there was music out there that no one really knew. "I want to know as much music as possible," he explained in a 2002 article, "confirmed in my earliest years that the unknown may offer the keenest delights." Havergal Brian was an early enthusiasm, and one of MacDonald's first trips to London was to hear Adrian Boult conduct Brian's massive Gothic Symphony in the Albert Hall in 1966.

By then he was a student of English at Downing College, Cambridge, but his true passion prevailed and he studied music in Cambridge for a further year. His first job in London was tape librarian of Saga Records, but its eccentric owner Marcel Rodd threw him out after three months: he asked about holiday pay.

That led to MacDonald's writing career: a temporary job in a record shop brought a contact with the editor of Records & Recording and an invitation to review. Since there was already a Malcolm MacDonald writing for Gramophone, he adopted the nom de plume Calum MacDonald, sticking with it even after the demise of his homonym. The composer and BBC producer Robert Simpson put him in touch with The Listener, starting a 43-year flow of journalism, and through its editor Karl Miller he came into contact with the musicologist David Drew, editor of Tempo, the contemporary-music periodical. In 1972 MacDonald became Drew's assistant.

From this point MacDonald's life was as uneventful as it was productive. In 1976 he met the artist Libby Valdez, and their relationship provided the emotional bedrock that sustained him for the rest of his life; they were finally married in 2011. Gradually taking over Drew's editorial functions at Tempo, he remained in the post until last December; Tempo became required reading for anyone interested in contemporary music. His four-year stint as compiler of the Gramophone Classical Catalogue in the mid-1970s he described as a job "to be wished on neither man nor beast".

In 1992 a move from London to Stanley Downton in Gloucester, to a house by the River Frome, enhanced his astonishing productivity. Even the four-year struggle with the cancer that killed him, and which he faced with realistic optimism, seemed unable to slow his output.

He had composed from his schooldays, producing mainly piano music and songs, lyrical and tonal, sometimes sweet but often with a dissonant bite. But he would talk about it only if you asked him; it was news to me, despite almost daily email contact over many years, that he was working on a large-scale orchestral piece when he died. A source of pride was his 1996 orchestration of the unscored final act of Roberto Gerhard's ballet Soirées de Barcelone.

The scope of his knowledge was exceeded only by the generosity with which he deployed it: musicians picked his immense brain, and his advice was always immediate and unstinting.

MARTIN ANDERSON

Malcolm MacDonald, musicologist, critic and composer: born Nairn 26 February 1948; married 2011 Libby Valdez; died Leckhampton, Gloucestershire 27 May 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks