Maureen Howard: Novelist of refinement and self-exploration

The writer had an unsentimental but perceptive view of her characters

Maureen Howard, a writer acclaimed for the mordant humour and refined, shimmering prose that often examined the lives of self-critical women seeking to find their place in the world, has died aged 91.

Howard published 10 works of fiction and a prize-winning autobiography during a writing career that began in the early 1960s. The settings of her books ranged from Italy to New York to her hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut, but all of them shared a graceful writing style and a clear-eyed, unsentimental view of her characters.

Her novels, which included Not a Word About Nightingales (1962), Bridgeport Bus (1965), Expensive Habits (1986) and Natural History (1992), were often called understated gems that deserved more attention than they received.

“It is hard to understand how a writer of Maureen Howard’s elegance, sharpness, sensibility and tenderness has escaped widespread public notice for so long,” author Doris Grumbach wrote in The Washington Post in 1982.

Almost 20 years later, in a New York Times essay, critic John Leonard was equally puzzled by Howard’s relative obscurity: “Why Howard isn’t cherished more is mystifying ... maybe it’s her refusal to compromise. She is almost too much for us.”

Howard’s first novel, Not a Word About Nightingales, was about a dreamy male academic who imagines himself leading a carefree life in Italy – while his wife and daughter remain in America. For her next book, Howard turned to the more familiar terrain of Bridgeport, where she had grown up in an Irish Catholic family.

Bridgeport Bus tells the story of a virginal 35-year-old woman, Mary Agnes Keely, who seeks to break away from the tight grip of her mother and asks the central question of the novel: “Is the mutually destructive love of mother and daughter more substantial than tidy freedom?” Seeking to find out, Mary Agnes takes a bus to New York, hoping to start a new life as a writer.

Mary Agnes hopes for an independent life, only to fall prey to a callous man who leaves her pregnant and with no alternative but to go back to Bridgeport. Reviewers likened Howard’s critical but loving descriptions of Bridgeport to the way James Joyce wrote about Dublin or William Faulkner depicted his fictional Yoknapatawpha County in Mississippi.

Bridgeport Bus came to be seen as something of a proto-feminist novel, and Grumbach wrote that it was “one of the most astutely funny novels of our time and no one I know who has read it has been able to forget it”.

In later novels, such as Before My Time (1975), Grace Abounding (1982) and Expensive Habits (1986), Howard’s characters – often writers – find their loftier aims crashing against mundane reality, as broken marriages, family responsibilities and creeping infirmity force them to examine the limits of their dreams.

“Not to be sentimental, that’s all I intend,” Laura Quinn, the central character of Before My Time, says in a terse self-assessment.

Readers and critics often lauded Howard’s prose style, which was often described as meticulous and spare.

“I like to leave something to the imagination,” she told Publishers Weekly in 1982. “The reader must fit the pieces together.”

In 1992, Howard published her longest and perhaps most ambitious novel, the 393-page Natural History. It was a family chronicle set largely in Bridgeport that experimented with elements of metafiction. In one section of the book, the novel’s narrative appeared on the right-hand pages, while the left-hand pages contained photographs, archival materials and musings about Bridgeport.

The book baffled many reviewers when it was published, but in a post on the Literary Hub website after Howard’s death, novelist Richard Powers wrote: “In a work like Natural History, she perfected a profound microscopic-macroscopic style built out of supple sentences that leveraged all the senses. She was the best of modernism wedded to a timeless introspection.”

Maureen Theresa Kearns was born 28 June 1930 in Bridgeport. Her father was a police detective, and her mother was a Smith-educated homemaker.

Howard portrayed her early life in her only full-length work of nonfiction, a 1978 memoir called Facts of Life, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction. Describing her demanding but colourful father, she wrote: “If he hadn't been my father I would have loved the spectacle he created ... like a versatile old vaudevillian with his audience (wife and child) in the palm of his hand.”

Her mother – who washed dollar bills in the sink, saying “money is so dirty” – took young Maureen and her brother to string-quartet concerts and insisted they study music and elocution.

“I sensed that my mother was a misfit from the first days when, dressed in a linen hat and pearls, she walked me out around the block,” Howard wrote in Facts of Life. “She was too fine for the working-class neighbourhood that surrounded us. ‘Flower in the crannied wall/I pluck you out of the crannies.’ Down Parrott Avenue around to French Street we marched, taking the air – ‘As I was going up the stair/I met a man who wasn’t there./He wasn’t there again today...’ I never knew when I was growing up whether my mother didn’t have time to finish the poems what with the constant cooking, cleaning, washing, or whether this was all there was, these remnants in her head.”

Howard graduated from Smith College in Massachusetts in 1952, then moved to New York, where she worked in advertising before her marriage to literature professor Daniel Howard in 1954. Her first book was published in England in 1960 and in the US two years later.

Her marriage to Howard and a second marriage to David Gordon ended in divorce. In 1981, she married Mark Probst, a lawyer, stockbroker and novelist. He died in 2018.

She and her husband were frequent hosts of literary cocktail parties at their home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where Howard often greeted guests by asking, “What are you reading?”

Howard taught writing at several universities, including Yale, Princeton, the City University of New York and, for about a decade, Columbia University. She also edited an anthology of essays and a collection of Edith Wharton’s short stories in the Library of America series.

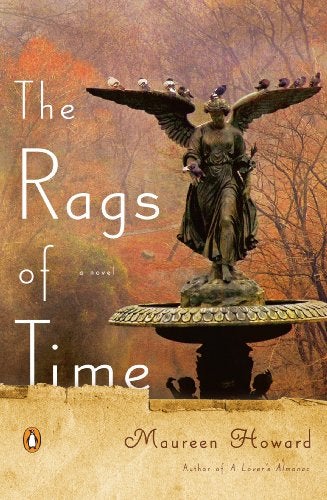

Between 1998 and 2009, Howard published a quartet of books loosely based on the four seasons: A Lover’s Almanac (1998) was set in the winter; Big as Life (2001) contained three novellas titled April, May and June; The Silver Screen (2004) ranged from New York to Hollywood and corresponded to the summer; and The Rags of Time (2009) offered a valedictory, autumnal view of life, touching on the Book of Genesis, Christopher Columbus and Franz Kafka.

Survivors include her daughter, a New York gallery owner, and two grandchildren.

From the beginning, Howard did not follow literary fashions and secured her reputation as a writer admired by other writers.

“It is hard to face your work each day and know that it may not be to the popular taste, and yet you can't care about that,” she said in 1986. “You do what you do according to what your imaginative talents are, you hang in there and have faith.”

Maureen Howard, novelist, born 28 June 1930, died 13 March 2022

© The Washington Post

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks