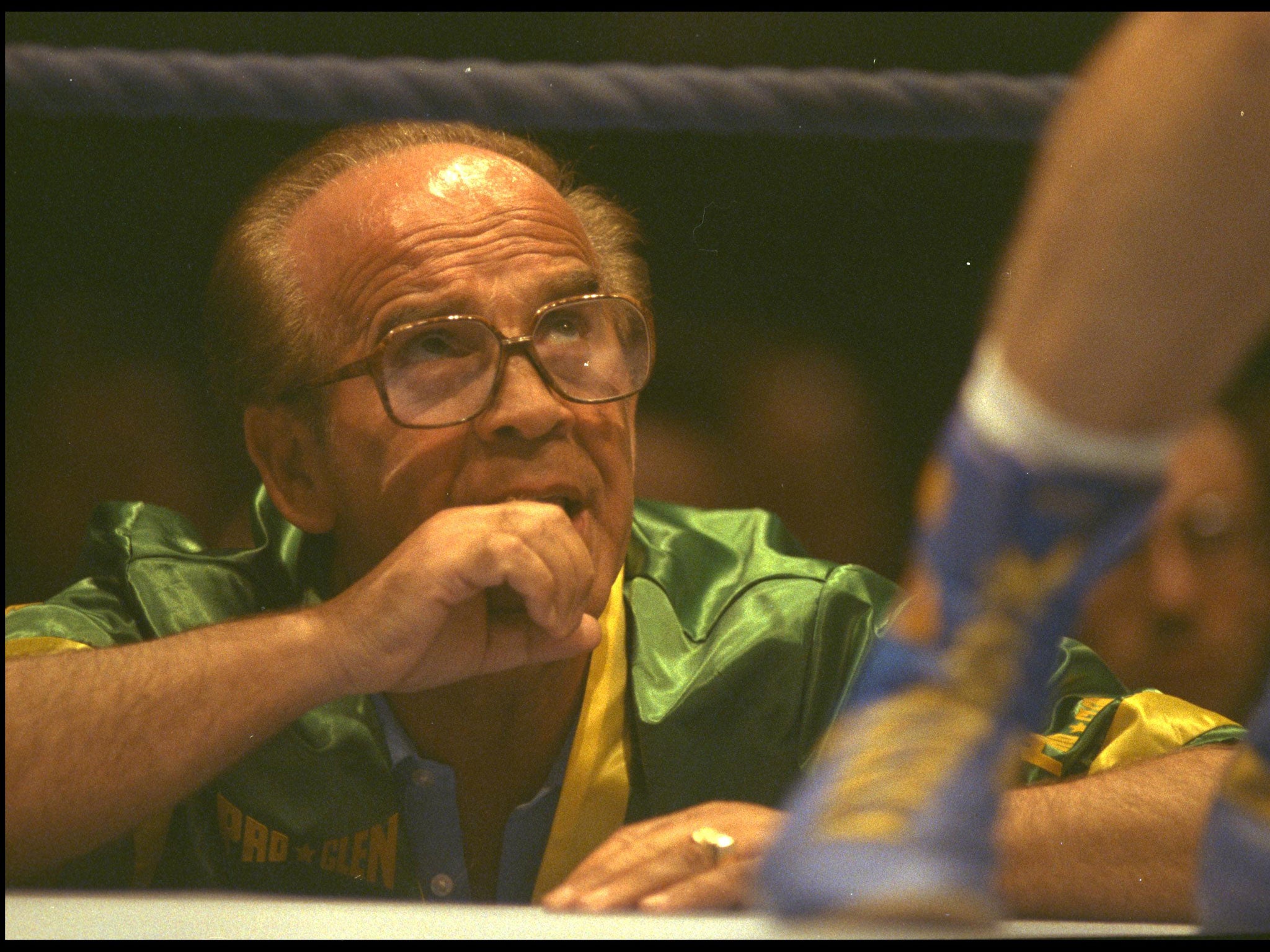

Mickey Duff: Boxer who retired at just 19 and became the British fight game’s most respected and feared manager and promoter

It is possible that Mickey Duff had the finest boxing brain, the sharpest tongue, the meanest spirit and that he was the hardest man to do business with. As he would say: “So, did I have any bad points?” Duff fought at all levels inside the ring before quitting at 19 to work on the other side of the ropes; he was first a matchmaker and eventually a manager, promoter and fixer in an international business that he loved. “Boxing is my business and my business is my life,” said Duff.

Duff, who was born Monek Prager, followed his father, a rabbi, from the small town of Tarnow, east of Krakow, Poland, and arrived in the East End in August 1938. He had a typically difficult life, not embellished by outpourings of familial love, in a city crowded with exiles and cowering each night from bombing raids. Duff’s family spent nights in Whitechapel tube, which did little to help him bond with his father, and the pair had stopped speaking, a rift caused by divorce, by the time Duff was about 13; they never spoke for 35 years and Duff refused to visit his father’s death bed.

He changed his name to Mickey Duff when he entered the London Schoolboy championships at some point in 1941 or 1942 and needed to fill out a form. The legend of the name has several tales about how and why Monek Prager became Mickey Duff. A character in a James Cagney movie and a film that does not even star the tiny hard man are most commonly mentioned as the source of the name change.

However, both connections are fantasy, bogus leads and a nice Duff invention. The truth, like a few instances in Duff’s life, was different; there was a boxer called Jackie Boy Duffy in the 1941 film, Ringside Maisie. The boxer was played by a real-life boxer called Eddie Simms, a heavyweight from Cleveland, Ohio, who fought between 1930 and 1949 and had over 100 fights, winning nearly half of them; he was the type of fighter Duff would have appreciated. The change in name was also a simple ruse to avoid detection by his parents, who never wanted him to fight.

Duff fought as an amateur and toured with the now defunct fighting booths, where he would appear in the crowd, posing as an innocent member of the public. The master of ceremonies would introduce the flat-nosed, gloriously named booth heroes and ask: “Is there a brave man out there willing to risk his life by going a round with one of these men?” It was Duff’s job to challenge them. Duff, who was scrawny, would get in the ring, survive and hopefully encourage other members of the crowd to pay for the same strange privilege. They would get brave, part with their cash and all fail.

When he was 15 and four months he lied about his age and had the first of 69 professional fights; he retired at 19 with 55 wins, six draws and eight defeats. “I was not that good, but I was making my own matches,” he said.

In the 1950s Duff was learning his trade, matching fighters for forgotten promoters like the Bodinetz brothers in lost locations like Leyton Baths. He became a fixture on the circuit; part pest and part boxing genius, with equal numbers of friends and enemies. “It was all I did, I had no other life,” he said. He was, however, brilliant at matchmaking.

Duff claimed connection to 19 world champions, though the list includes fighters he had no involvement with when they won world titles. His first was Terry Downes, who Duff matched in the 1950s and ’60s. Downes won the middleweight world title in 1961, which is amazing considering the rare bad match Duff had made for him in 1957 at Shoreditch Town Hall.

Duff picked an unknown African emigrant called Dick Tiger, who stopped Downes after six brutal rounds. In the changing room after the fight Downes was asked who he wanted to fight next and, with a cold look in Duff’s direction, said: “The bastard who made this match.” In typical Duff fashion, he retold the story celebrating the fact that he had matched two future world champions together for just £195, including expenses. “A year later, it would have been 10 times that amount,” he said. By the way, when Mickey told the story it lasted longer than the fight.

Duff took control of British boxing in the 1970s when he formed a legal cartel with Mike Barrett, Jarvis Astaire and the boxing trainer Terry Lawless. The cartel, dominated by Duff’s boxing brain, enjoyed a 30-year monopoly with the BBC and had a hold on the best and biggest venues in London. Under their ruthless reign Charlie Magri, Jim Watt, John H Stracey, Alan Minter, John Conteh and Maurice Hope all became world champions in the 1970s. Duff also forged a relationship with Muhammad Ali on both sides of the ropes, which was touching at times.

“I made enemies and people resent the way I do business,” Duff said. “That’s life.” He banned me for three years then told me he regretted it and thanked me when the paper I worked for at the time settled with him. Duff genuinely never cared what other people in the boxing world thought of him, which is a polite way of saying he had the thickest skin in the business, and he gently altered veteran boxing promoter Harry Levene’s axiom. Levene always said: “It doesn’t matter if you are rich or poor – as long as you’ve got money.” Duff, who operated in vicious times, added an alternative and bitter ending. “…as long as you’ve got fuck ’em money.” An hour in Duff’s time would always include that line.

In the 1980s the cartel’s hold, dominance and what many considered abuse was finally broken when Frank Warren entered the business. Duff’s fighters started to leave him and led to Duff’s succinct assessment of the business to which he had devoted his entire life: “If you want loyalty, get a dog.” When Duff said it there was no comedy attached, which is odd, because he was a funny man.

Monek Prager (Mickey Duff), boxer, manager and promoter: born Tarnow, Poland 7 June 1929; married Marie (separated; one son); died London 22 March 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments