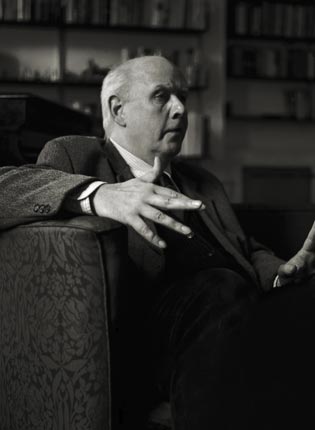

Patrick O'Connor: Critic, author and broadcaster with particular expertise in vocal music

The many friends who loved him knew the critic, writer and broadcaster Patrick O'Connor as a polymath repository of knowledge. His subjects ranged from music hall performers to French poster art, from cinema to ballet, and from opera to food. With a forever-youthful sparkle in his eye and a talent for friendship, he was a large cuddly bear of a man, tall and sometimes mistaken for the actor, Peter Eyre. Despite his profound expertise, especially in vocal music – he was the first person you'd consult if you wanted to know something about a long-gone music hall performer or a 19th century operatic soprano – he was almost entirely self-taught.

Born in London, Patrick O'Connor was the elder child of Armand Stiles O'Connor (always known as Paddy, he was born in Glasgow, though his own father, who died before his birth, was American) and Peggy Constance Blandford. His father's Merchant Navy ship was torpedoed, and Paddy O'Connor was reported missing, thought killed in action – but following the War he turned up safe and alive in Glasgow. A publisher of specialist medical and dental magazines, Paddy O'Connor was also a large, jovial man, who died in 1999. Patrick had a younger sister, Louise, and an elder sister, Patricia, from his mother's previous marriage.

At first the family lived near Paddington Green, where they had easy access to cinemas and to the Metropolitan Music Hall on Edgware Road, where a precocious Patrick remembered seeing Max Miller. In the mid-1950s they moved to a large, semi-detached Victorian house in Richmond, which housed the various magazine businesses as well as the family. He went to Surbiton County Grammar School, which he loathed and left at 15, saying that the day he left school was when his life began. He had been a plump child, but on leaving school he lost weight and became a strikingly good-looking young man. At first he worked for his father as the production editor on the medical journals.

Soon he had a new circle of friends. The most important, at first, was the slightly older Jeffrey Tate, with whom he travelled to Venice. He enjoyed introducing his friends to each other, and had a wide circle, including the American sociologist, Richard Sennett; and, during the last two years, delighted in the company of a rediscovered nephew, Tim Fleming. He had five surviving nephews, and took much pleasure in them. We shared a godson, Leo Hornak; and I suspect that Patrick was the better godparent.

The Richmond house was a mixed blessing. He stayed in it after the businesses were sold, and his mother died in 2001, but he found that the dash for the last train from Waterloo blighted his cultural and social life; and he felt that existence had almost begun anew recently when he sold it and moved to a new flat in Bloomsbury. (While that was being refurbished, he was a lodger in Virginia Ironside's house, his room so packed with books and gramophone records that he only once allowed her in it.) As at the Richmond house, the walls of the flat displayed his collection of old opera and ballet posters, drawings and etchings of Gertrude Stein and Diaghilev, of Yvonne Printemps and Josephine Baker (of whom he wrote biographies), photographs of ancient actresses and music hall turns, and paintings by his friends, particularly Glynn Boyd Harte (who made a portrait of him) and the American garden designer, Hitch Lyman. A generous host and cook, O'Connor loved good food and wine, and knew a good deal about it.

O'Connor's pleasant voice made him good radio company, and most people will have known him as a frequent contributor to Radio 3's CD Review, where he was often to be heard talking about the French repertory, Reynaldo Hahn, Francis Poulenc, or discoursing on his vast acquaintance with Belle Époque opera and operetta.

He wrote for a huge variety of papers and magazines, including this one. The Times Literary Supplement recognised his catholicity of interests by allowing him to review a wide range of performances and books. From 1981 to 1986 he was employed by the old Harper's & Queen, then in its features-oriented heyday of Sloane Rangers and Foodies, and worked closely with Ann Barr. Here he was properly valued for his encyclopaedic knowledge of just about everything. But in 1988 he surprised us all and moved to New York, to be editor-in-chief of Opera News, published by the Metropolitan Opera Guild. Though this allowed him to meet some composers he idolised, such as Virgil Thompson and Ned Rorem (who became a friend and correspondent), New York wasn't entirely a success. So when he got involved with the US Immigration services in the usual green-card wrangle, and the official, looking at his job description, said he could see no reason why an American could not be doing the job of editing Opera News, O'Connor said, "You're quite right," and happily upped sticks back to London.

It is not hyperbole to say that O'Connor's knowledge of some subjects was probably unique. We have to hope that he wrote it all down somewhere, and that someone will undertake what will be the enjoyable task of collecting Patrick's pieces and unpublished work. The substantial obituaries of artistes he wrote for The Guardian alone contain a wealth of fugitive information. His books included the life of Yvonne Printemps (1978, self-published, but he managed to talk Sir John Gielgud into writing the introduction); Josephine Baker (1988), with photographs from Bryan Hammond's collection, The Amazing Blonde Woman: Dietrich's Own Style, 1991); and, the same year, Toulouse-Lautrec: The Nightlife of Paris, which my wife, who commissioned it from him for Phaidon, considers one of the great pleasures of her own career.

Paul Levy

Patrick O'Connor, critic, writer, broadcaster, collector; born London 8 September 1949; died London 16 February 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks