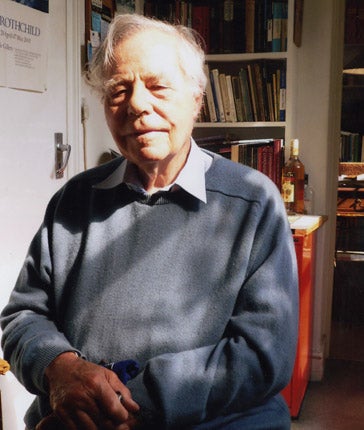

Professor John Waterlow: Physiologist celebrated for his achievements in the field of childhood malnutrition

John Waterlow enjoyed international acclaim for his lifetime of work on the scientific basis and medical treatment of childhood malnutrition. He leaves a legacy of devotion to the betterment of humankind worldwide.

John Conrad Waterlow was born in 1916, the son of Sir Sydney Waterlow and Helen Eckhard. His father held various posts and international assignments in the Foreign Office, as well as spending time as a writer and critic. His mother came from a well-to-do Manchester family descended from German immigrants, with a heritage of support for the arts.

Due to his father's wide-ranging social network (including membership of the Bloomsbury Group), John grew up in an intellectually stimulating environment. Visits by the likes of EM Forster, Desmond MacCarthy and Virginia Woolf were not uncommon. Despite the literary ambience, it was a family friend from the sciences, the chemist George Barger, who John remembers as having the most influence on him as a child. His parents also instilled in him a lifelong penchant for the outdoors and walking.

Following his father, John was schooled at Eton, and, like his father, won the Newcastle Scholarship in classics and divinity, the school's major award. He had no aspirations towards academia, law, civil service or the church – the sort of occupational tracks to which the scholarship usually led. John's mind was expanding into "the world outside Eton", as he later recalled. A lecture on leprosy in West Africa by the Reverend Philip "Tubby" Clayton (founder of the welfare organisation Toc H) turned him toward medicine and world health, following Clayton's advice. Entering Cambridge in 1935 with an entrance scholarship in classics, Waterlow changed to medicine. He matriculated at Trinity College 1935-39, getting a first in physiology. He joined the Communist Party for a time, volunteering to go to Spain, but he was told by the party boss to finish his medical degree.

In 1939 Waterlow married Angela Gray, a Cambridge history student who became an accomplished artist. With the outbreak of war, he enrolled at the London Hospital Medical College; giving assistance during the Blitz was de rigueur for him and his fellow medical students. Qualifying in 1942, he was assigned to the Medical Research Council's military personnel research programme under BS Platt. He spent a year examining heatstroke and heat exhaustion at in Basra. At the war's end Platt became director of a new MRC Human Nutrition Research Unit and persuaded Waterlow to join, imprinting indelibly in his memory the prediction: "Nutrition will be the problem of the future".

In 1945 Platt sent Waterlow to the Caribbean on behalf of the Colonial Office to determine why so many infants and young children were dying there. He spent a year in Trinidad, Guyana, and Jamaica, developing a lasting commitment to the region. The crucial concern in his Caribbean studies was the understanding of the pathophysiology of frequently fatal infantile malnutrition. Waterlow discovered that the clinical syndrome he observed was identical to the malnutrition condition termed Kwashiorkor some years earlier in Africa. With a keen empirical eye and an inventiveness in the use of experimental instrumentation, he set out to elucidate the biochemical foundation of the malnutritional state, carrying out similar studies at field stations in Africa, notably Gambia and Basutoland (now Lesotho).

The lure of the West Indies exerted a strong pull on Waterlow and his family: in 1948 the University of the West Indies was founded in Jamaica, and he secured a part-time job as physiology lecturer and MRC researcher in late 1950, continuing his clinical studies there for three years, initially allotted a wooden hut for his lab and aided by one technician. He also took part in a number of exploratory expeditions to the Andes, studying high-altitude physiology, using himself as a subject.

In 1954 he persuaded the MRC to establish a Tropical Metabolism Research Unit; the TMRU acquired its own building in 1956. Waterlow was joined by Dr Joan Stephen, who became his research assistant and lifelong companion. He served as director of the TMRU from 1954-70, a seminal period not only in defining his professional stature in world public health, but also in generating research that would save lives. Waterlow attracted leading researchers and garnered large amounts of funding. During the 1960s, he and colleagues published classic and far-reaching studies on protein-energy malnutrition (PEM). In 2006 he traveled to Jamaica for the last time, for the TMRU's 50th anniversary celebration; the programme was subtitled "The House That John Built".

He returned to England in 1970 to become Professor of Human Nutrition at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, a post vacated by Platt's death. He revamped the School's research thrust and expanded its training mission, establishing the Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism Unit. By this time he was a leading authority on human nutrition. Over the years he served on a variety of committees and groups. In the UK, he was appointed Adviser on Nutrition for the DHSS and Consultant on Nutrition for the Ministry of Overseas Development. He retired from the LSHTM in 1982, the same year he was elected FRS.

The term "retirement" did not fit Waterlow's life trajectory. In 1984 he was appointed chair of the MRC's Army Personnel Research Committee, and served as President of the UK Nutrition Society (1983-86). He published prolifically almost until his death, including updated editions of the influential Protein Turnover (2006) and Protein-Energy Malnutrition (2006). He remained attuned to global humanitarian issues throughout his life.

He was also an inspiring teacher, mentor, colleague and friend to many. He was a person of far-ranging intellectual interests, a voracious reader, a conversationalist in many fields and a bon viveur. In his presence one sensed a towering mind but a generous and humble spirit. As trite as it may be to say, the world is a better place due to John. The lives of countless impoverished people have been saved. The lives of countless others have been enriched. I count myself in that number.

It was at the Royal Institution of Great Britain that my friendship with John Waterlow began in the spring of 1987, writes Sir John Meurig Thomas. He had contacted me following my inaugural Discourse as Director (on "The Poetry of Science") in November 1986; and he had heard me mention the initiative taken by my predecessor Sir George (later Lord) Porter in setting up mathematics master classes on Saturday mornings at the RI for teenagers.

One day in March 1987 he brought into the Director's office his lifelong friend, Colonel Jimmy Innes. They told me that their mission was to find the resources to extend the RI master classes to locations throughout Britain, especially to areas of high unemployment. "Ever since we were at school together we have each felt that mathematics holds the key to an efficient country." They elaborated that, in their opinion, if a strong case were made for extending these classes nationwide, the Livery Company of Clothworkers (of which they were members) would look kindly upon such a proposition.

The upshot was the allocation of a massive grant of £750,000 to enable the RI master classes to continue. There was much excitement when The Duke of Kent, President of the RI, hot-foot from Wimbledon, unveiled a plaque in Albemarle Street to mark this event in the summer of 1989.

Two other unusual aspects of Waterlow's activities were associated with the RI. First, I persuaded him to give a Friday Evening Discourse in February 1990 on "What they ate in ancient Greece and Rome". Even now, the content of that talk still resonates. He told his audience that the rich people of classical Greece and Rome had diets of extraordinary variety and quantity, but the diet of the poor was monotonous, consisting largely of wheat or barley, beans, a great range of fruit and vegetables, with olive oil, cheese and occasional fish and meat. "This pattern," he said "corresponds closely with what we now regard as a healthy diet".

He wrote in his abstract for that event: "The expectation of life at birth was only 30 to 35 years, comparable to that of England in the Middle Ages, but long enough to allow for children to be born and the population to expand. The reason for life being so short seems to have been infectious disease rather than malnutrition, with important contributions from war".

The second aspect of his links with the RI reflects his thoroughness as a scientist. He asked me whether I could find a bright young graduate well- versed in mathematics to guide him in pursuing quantitatively some of his theories and speculations. I approached another ardent supporter of the RI, Professor (now Sir) John Pendry of Imperial College, who identified one of his young students, Keith Slevin, now Physics Professor at Osaka University. Slevin was able to formulate equations, solve them and plot graphs pertaining to protein pools and lifetime kinetics. When Slevin moved to pursue post-doctoral work in Paris, John occasionally visited him since he frequently lectured to doctors involved with Médicins Sans Frontières. The collaboration continued after the junior partner moved to Japan.

John Waterlow was a compassionate and charming individual with a voracious intellectual appetite and was always sympathetic to the underdog and underprivileged people, wherever they were.

John Conrad Waterlow, physiologist: born 13 June 1916; Director, Medical Research Council Tropical Metabolism Research Unit, University of the West Indies 1954–70; Professor of Human Nutrition, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine 1970–82, then Emeritus; CMG 1970; married 1939 Angela Gray (two sons, one daughter; died 2006); died 19 October 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments