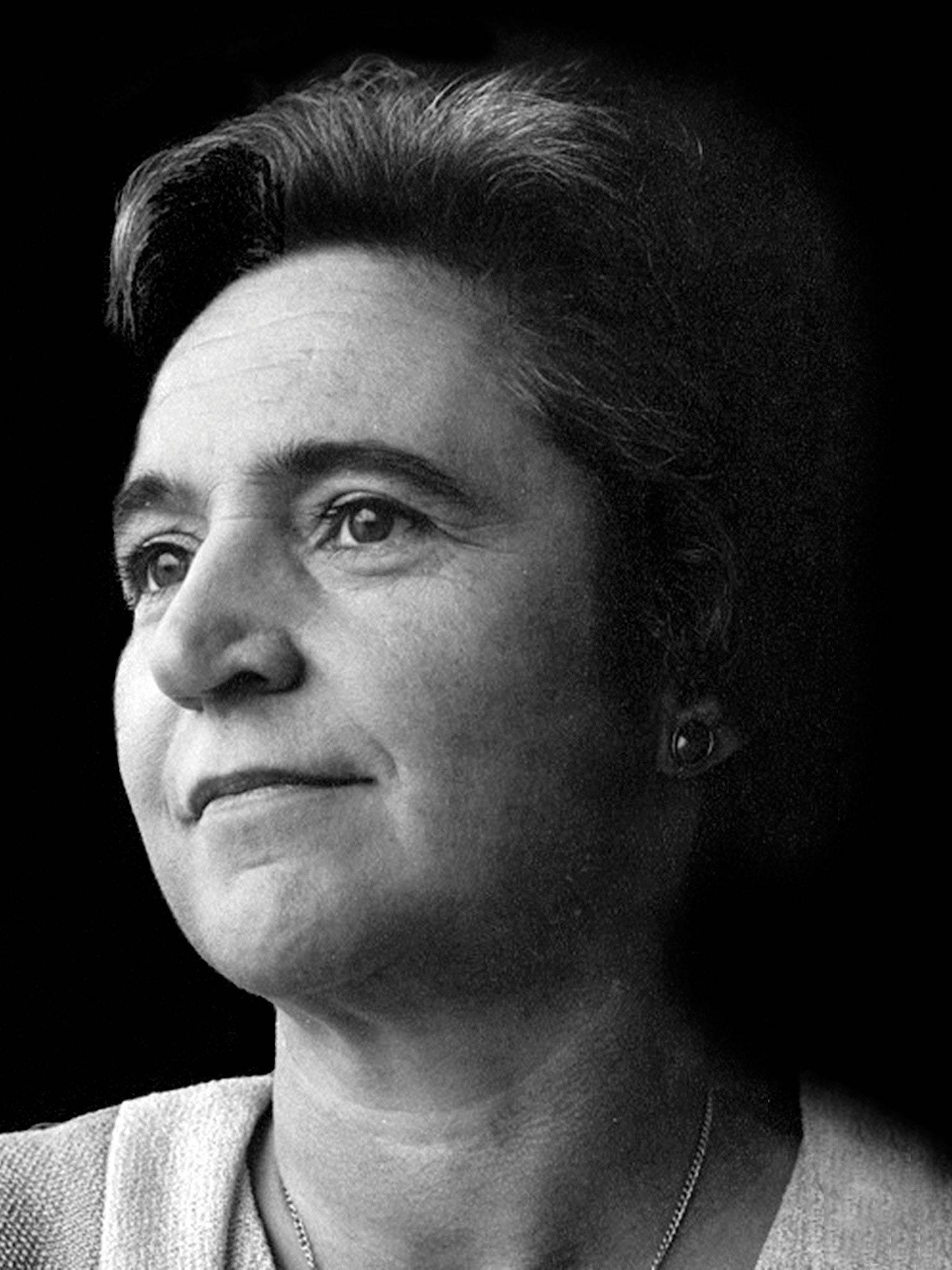

Professor Olive Stevenson: Academic whose work helped pave the way for effective provision of child protection services

Olive Stevenson could not have foreseen the great consequences for her when, 40 years ago, she wrote a dissenting addendum to the report of the inquiry, of which she was a member, into the death of Maria Colwell, a child who had been killed by her stepfather. It gave her an unwanted celebrity status which unleashed invitations to lecture and speak and projected her on to the national stage.

However her dissent – she disagreed only with the analysis of the events in the first part of the child's life – could have been avoided had the inquiry chair, Thomas Field-Fisher QC, been more flexible and understood better the issues. She later wrote that his and her values were fundamentally different. But while she never wished what she wrote to be seen as a defence of social work, right or wrong, she felt compelled to explain the complexities of social work. But she also wrote the chapter on collaboration between services in child protection, a commonplace place today but the importance of which was then little realised.

Stevenson was born in 1930 in Croydon and grew up in Purley, the youngest child of John and Evelyn (née Dobbs), a civil servant and housewife. Her parents were Irish non-churchgoing Protestants who had come to England from Dublin fearing discrimination by the new Catholic Free State.

Their daughter, a youthful Congregationalist who became an agnostic, remained deeply distrustful of Catholicism. When at the local Whitgift Girls School she told the headmistress that she wanted to do psychology when she grew up, her mother was told that she should not read Freud. She did, and at 17 worked as an assistant house mother in a Croydon children's home.

She went up to Oxford in 1949 to read English, spent two vacations volunteering at the Mulberry Bush School for emotionally damaged children and then trained on the two-year LSE child care course. From 1954-58 she was a child care officer in Devon and left to take the 10-month advanced social casework course at the Tavistock Clinic. She gained a taste for psychoanalytic social work. Later in life she defended and advocated psychodynamic social work when it came under attack from the Marxist-inclined "radical social work" school for its alleged "pathologising" of the poor. But she never ignored the economic and social influences on clients' lives and believed the polarisation of approaches only further disadvantaged children and families.

After "the Tavvie" she moved to Bristol University in 1959, working as social work researcher and tutor, and in 1962 she assumed a lectureship (and later readership) in applied social studies at Oxford, where she was later professorial fellow at St Anne's. While there she spent a year as adviser to the Supplementary Benefits Commission, from which came Claimant or Client? (1972), when she saw the issues as relevant to wider social policy as social security.

Her first book, published in 1964, had been a guide for foster parents and she was to write and edit eight more and co-edit and co-write others. She was also the founder and first editor of the British Journal of Social Work. In 1976 she went to Keele as its first female professor and in 1984 took the chair in social work at Nottingham. Her overseas work included visiting professorships in Israel and Australia and supervising PhD students in Hong Kong, while in China she was part of the development of Beijing University's growth of social-work training.

In retirement she became one of the first chairs of an area child protection committee (now local safeguarding boards). She also continued to teach and write and supervise research students and only left Nottingham properly in 2010. From the 1980s she started to write and lecture extensively about older people, being at one time chair of Age Concern England. Her work on child protection caused her to link that with the parallel but then far-less recognised subject of the abuse of older people.

In her recently published memoir, Reflections on a Life in Social Work, she wrote openly about her lesbianism, having lived for much of the time when it was surrounded by secrecy and stigma, which personally caused her unease. Her wit, practical wisdom, intelligence and an ability to weld an elegant and brilliant synthesis between social policy and social work practice were a hallmark of her work, which influenced generations of academics and practitioners. All this was underpinned by her quest for how both she and her students and readers could use mind and feelings ("heart and head") together.

Although Stevenson could appear forbidding, it is obvious from her memoir that beneath the carapace of the professional self-assurance and eminence lay anxieties and complexities with which she had to cope all her life, and the struggle to be "freed to be myself". She wrote of relationships (while not mentioning individuals) that were "fraught with tension and pain" and took her to undergo psychoanalysis.

She died guardedly optimistic that a positive change was coming to social work. Managerialism and central diktat had obscured its vision and ethical basis, which she wanted to it rediscover. They were qualities which her own work strove to engender.

Terry Philpot

Olive Stevenson, social worker and academic: born South Croydon 13 December 1930; CBE 1994; died Oxfordshire 30 September 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks