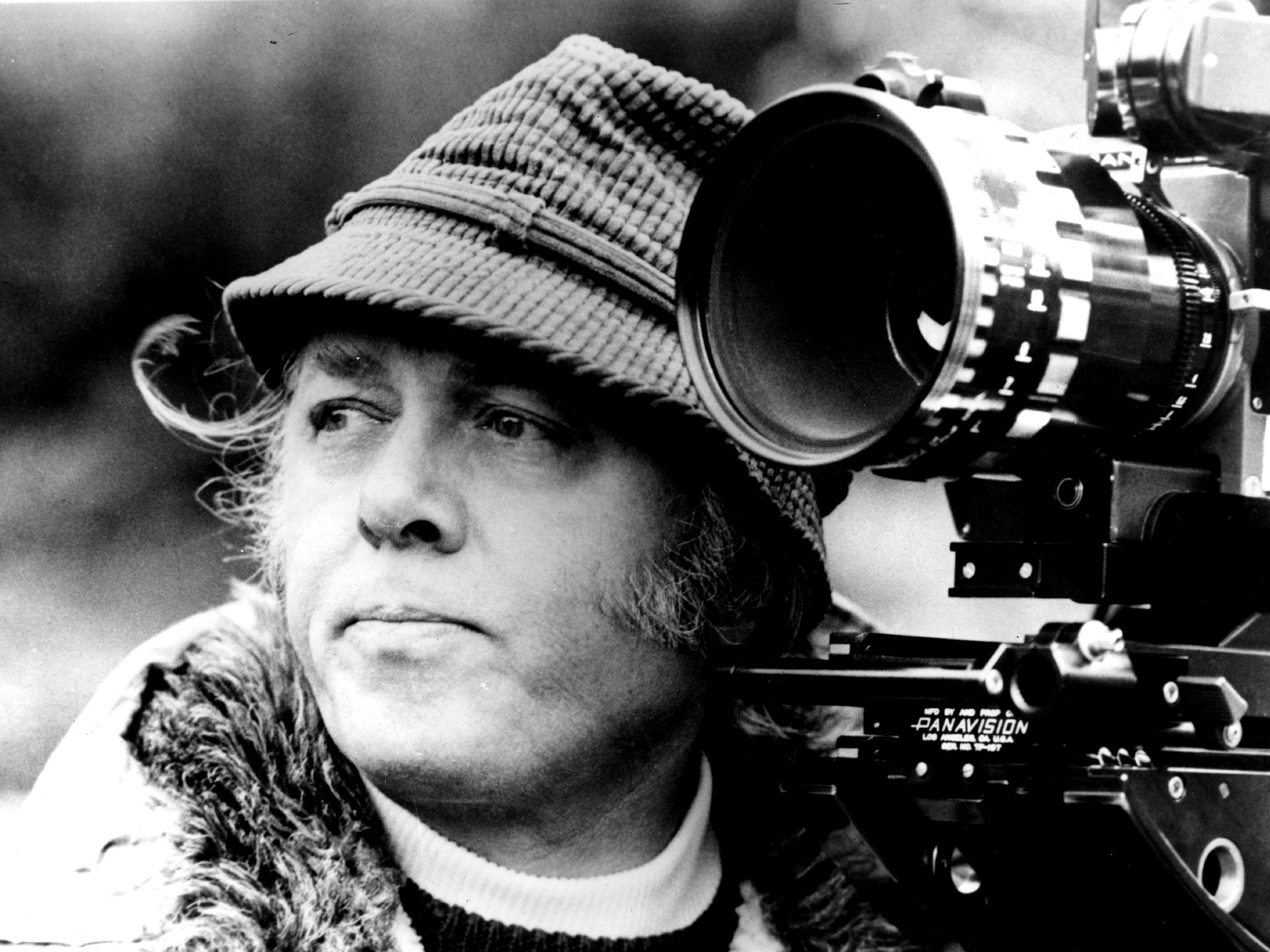

Richard Attenborough: One of the leading figures of British cinema

The acclaimed actor and director was a tireless champion of the British film industry and liberal causes in the last half of the 20th century

Lord Richard Attenborough was not only one of the prime figures in British cinema in the last half of the 20th century, acclaimed as both an actor and director, but he was also a tireless champion of the British film industry and liberal causes.

It could be said that as an actor he was underrated, partly due to his typecasting as callow or cowardly ratings in his early films, and as a director may be overrated, though he often chose brave projects that required yeoman logistic capabilities.

For the celebrated film Gandhi, for which he won two Oscars, as producer and director, he marshalled over 200,000 extras for the funeral scene, reputed to be the largest number of players ever on screen at the same time. His deep concern for freedom of speech and liberal values were evident in his most personal films, which depict the life of Mahatma Gandhi and Steve Biko, but some assignments saw him over-stretched, such as A Bridge Too Far, which in depicting the chaos of the Arnhem landings proved a chaotic movie, and his misbegotten transcription of the Broadway musical, A Chorus Line.

As an actor, his range was awesome – the irredeemably wicked young gangster of Brighton Rock, the cocky schoolboy of The Guinea Pig, the taxi driver determined to clear his name in Dancing With Crime, the wily soldier of Private’s Progress, the stoic worker defying his mates in The Angry Silence, the chief organiser of The Great Escape, the fraught father in Séance on a Wet Afternoon, the tough sergeant of Guns at Batasi, the hilariously camp antiquarian in The Third Secret, the heart-breaking, tragically lovesick stoker of The Sand Pebbles, the singing and dancing circus master of Dr Dolittle, the sinister killer of 10 Rillington Place and the avuncular Kris Kringle of Miracle on 34th Street are just a handful of 70 film performances.

His marriage in 1945 to Sheila Sim endured until his death, and he was confronted by appalling tragedy when one of his daughters, a grand-daughter and his daughter’s mother-in-law were killed in the Tsunami caused by the Indian Ocean earthquake on Boxing Day 2004.

His diverse corporate appointments included Governor of the National Film School, Trustee of the Tate Gallery and Chairman of Chelsea Football Club. In memory of his daughter he founded the Jane Holland Creative Centre for Learning at Waterford Kamhlaba in Swaziland, which promoted his passionate belief in non-racial education.

Awarded the CBE in 1967, he was knighted in 1976, and in 1993 he was made a life peer, sitting in the Lords as Baron Attenborough of Richmond upon Thames. Though he was a fervent Labour supporter, his friends included Prince Charles and other establishment figures. Attenborough was close to Princess Diana and taught her (at her husband’s request) how to make speeches and to feel comfortable dealing with large crowds. He and his wife often had the Princess to lunch, and became confidantes whose discretion she trusted.

The son of a college administrator who became principal of University College Leicester and who wrote a standard text on Anglo-Saxon law, he was born Richard Samuel Attenborough in 1923, the oldest of three brothers – the youngest, David Attenborough, is the naturalist and television presenter. Their mother was president of Leicester Little Theatre, and Richard became interested in acting while in his teens.

At the age of 17 he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, and while studying there in 1941 he made his stage debut at the Intimate Theatre, Palmers Green, playing the lovesick teenager Richard in Eugene O’ Neill’s Ah, Wilderness. In 1942 he was given his first screen role, as a submarine stoker, who deserts his post in Noël Coward’s stirring tribute to the Navy, In Which We Serve (1942). “If you blinked, you missed me,” he later said, “but getting to know Noël was the great thing. He was the most influential and supporting figure of my early life.”

Attenborough then gave a chilling depiction on stage of the venal Leo Hubbard in Lillian Helman’s The Little Foxes (1942), which opened during a thick London fog and lasted for only three weeks. The following year he was given the lead in a stage version of Graham Greene’s novel Brighton Rock, in which he played the vicious psychopath, Pinkie Brown. Both he and another newcomer, Dulcie Gray, won praise for their contrasting portrayals of evil and good. “Dickie asked me to take my shoes off during auditions because he was very short,” recalled Gray, “but he was very attractive in those days with his large eyes, snub nose and sensual mouth.”

Attenborough served in the RAF for the rest of the war, then on demobilisation he married a fellow student he had met at Rada, Sheila Sim. Journey Together (1945), a propaganda piece made to promote Anglo-American relations, teamed Attenborough with Hollywood veteran Edward G Robinson, and though it fulfilled its purpose entertainingly it helped establish the association of Attenborough’s image with that of nervousness and inexperience.

The film version of Brighton Rock (1947) helped break the mould, thought there were elements of the stereotype in his brash and boastful youth who becomes a frightened killer in London Belongs to Me (1948). His baby-face looks helped make him a convincing schoolboy in the Boulting Brothers film The Guinea Pig (1948), a tale inspired by the recently passed law that allowed working class boys to attend public schools. He was a scared rating again, this time on a submarine, in the gripping Morning Departure (1950).

The same year he starred with his wife and Yolande Donlan in a hit stage comedy, To Dorothy a Son, as a harassed father-to-be, and he played a similar role on screen in Father’s Doing Fine (1952), the first film for which he received star billing. In late 1952 he and Sim had no idea that they were becoming part of theatre history when they opened at the Ambassador’s Theatre in a cosy Agatha Christie thriller that was expected to run for a year or two. It was The Mousetrap, which celebrated its 61st birthday last November. Attenborough played Sergeant Trotter for two years, after which he returned to the screen in three hit comedies for the Boulting Brothers, Private’s Progress (1956), Brothers-in-Law (1957) and I’m Alright Jack (1959), which satirised the military, the law and trade unions respectively.

His prolific film roles included The Ship That Died of Shame (1955), Dunkirk (1958), The Man Upstairs (1958), Danger Within (1959, and the extremely popular caper movie The League of Gentlemen (1959), which was written by his friend Bryan Forbes. In 1960 he and Forbes formed a production company, Beaver Films, and for their first film they bravely tackled the subject of strikes, which Attenborough (after Kenneth More turned down the role) playing a worker who refuses to join an unofficial strike and is sent to Coventry by his colleagues.

Beaver had its greatest success with Whistle Down the Wind (1961), though Attenborough did not appear in it, nor another Beaver production, The L-Shaped Room (1962). The first major American production in which Attenborough appeared, and one of the biggest hits of his career, was The Great Escape (1963), in which he played the officer who masterminds the meticulously detailed plan for a massive prisoner-of-war break-out. He was one of the few actors to establish a relationship with the moody Steve McQueen.

He then starred in the final Beaver production, Séance on a Wet Afternoon (1964). His uncompromising performance as the fraught husband of a crazed medium (Kim Stanley) was a role he used to cite as his favourite. Though a failure in its day, the film now has a cult reputation. Arguably at his peak as an actor, Attenborough was superb as a sadistic sergeant in Guns at Batasi (1964), and as the navigator of an aeroplane that crashes in the Sahara Desert in Flight of the Navigator (1965).

McQueen then suggested that Attenborough appear with him in the epic movie The Sand Pebbles (1966) as the stoker on a gunship patrolling the Yangtse River in 1926 who has a doomed love for a Chinese girl who has been sold into prostitution. His immensely moving portrayal won him a Golden Globe Award as best supporting actor. Surprisingly, although he won many awards, including several Baftas, he was never nominated for an acting Oscar. He then surprised audiences with a roistering song-and-dance turn in Dr. Dolittle (1967), his ebullient, music-hall delivery of the song “I’ve Never Seen Anything Like It” providing a rare lively moment in an elephantine movie.

In 1969, already nursing an ambition to make a film on the life of Mahatma Gandhi, he accepted an assignment to direct a film version of Joan Littlewood’s revue-style stage success based around the songs of the First World War, Oh What a Lovely War! The show traced a delicate line between sparkling song-and-dance entertainment and the harsh realities of trench warfare, and was not an easy project to transfer to the screen.

Attenborough set most of the show on Brighton Pier, and achieved at least one superb directorial touch – a young man is seduced into fervently enlisting the vision of a glamorous showgirl (Maggie Smith) singing “I’ll Make a Man of You”, then as he mounts the music-hall stage he has a rude awakening as he comes face to face with the coarse, heavily made-up performer. The film’s final shot – an aerial view of masses of graves of those fallen in the war while on the soundtrack a soldier’s chorus sing ironic lyrics to the melody of Jerome Kern’s “They’ll Never Believe Me” – was devastating.

Having almost imperceptively made the transition from leading man to character actor during the 1960s, Attenborough returned to the screen as a quirk detective inspector in a film version of Joe Orton’s play, Loot (1970), and played a psychologist having an affair with his half-sister in A Severed Head (1970). A fierce opponent of capital punishment, he readily accepted the role of serial killer John Christie in 10 Rillington Place (1971), in which he gave a chilling performance equalled by that of John Hurt as the wrongly executed Timothy Evans.

Attenborough’s second film as a director was Young Winston (1972), based on Winston Churchill’s book My Early Life. Starring Simon Ward, the film efficiently depicted a young man’s progress through his schooling, his experiences as a journalist in Africa (with a rousing recreation of the Battle of Omdurman in 1898) and his induction into Parliament, but it was given a complex flashback and narration structure, the sort of elaboration that was to mar Attenborough’s later biography of Charlie Chaplin.

He next directed A Bridge Too Far (1977), an account of the Battle of Arnhem in the Second World War, written by Cornelius Ryan, who wrote the D-Day film The Longest Day, which had already been filmed with great success. Attenborough’s film had a similar all-star cast – when Steve McQueen turned down the leading role, Attenborough successfully pursued Robert Redford – and though the pace is slow and the narrative confusing, the film’s battle scenes are awesome and the film did well at the box office.

The following year he directed his first Hollywood film, Magic, a thriller in which a ventriloquist is possessed by his dummy – most critics agree that the earlier film, Dead of Night, handled the subject more effectively. Then in 1982 he achieved his long-standing dream of bringing the life story of Gandhi to the screen. His painstaking account of the life of the Indian promoter of protest through non-violence was his greatest directorial triumph, gaining 11 Oscar nominations and winning eight, including those for Ben Kingsley as Best Actor and Attenborough as Best Producer and Best Director.

Another project close to his heart was Cry Freedom, which starred Denzel Washington as the anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko. Reaction to his treatment of the tale was mixed, since in order to make the downbeat story palatable (Biko died in police custody) , he devoted the film’s second half to the journalist Donald Woods, whose fearless revelations about Biko’s treatment put his own life in danger. Woods’ flight from South Africa with his family reminded some critics of The Sound of Music and was thought to diminish the impact of the Biko section.

Chaplin (1992) was the biography of another of Attenborough’s heroes, Charlie Chaplin, and he was particularly lauded for the fine performance he elicited from Robert Downey Jr. Shadowlands (1993), based on the romance between the academic and author CS Lewis and the poet Joy Gresham, was another example of his skill with performers. Attenborough had difficulty finding backing for later projects, selling part of his valuable art collection to raise funds, and the Irish love story, Chasing the Ring, was little seen.

He acted in few films later in his career, but had notable success as an eccentric developer in Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) and its sequel, and as a twinkly Kris Kringle in The Miracle of 34th Street. After a stroke and a fall, Attenborough sold his Richmond home and in 2012 moved with his ailing wife into a rest home.

Richard Samuel Attenborough, actor, producer and director: born Cambridge 29h August, 1923; CBE 1967, Kt 1976, cr. 1993 life peer; married 1945 Sheila Sim (one son, one daughter, and one daughter deceased); died London 24 August 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks