Rick Mather: Architect hailed for his subtle and light-filled renovations of historic buildings

The architect Rick Mather is celebrated for renovations of British museums and galleries that amounted to re-founding them, because with subtlety, refinement and, above all, respect for their traditions and collections, he made historic spaces work as modern institutions. His great imaginative gift was to take a dark or enclosed space and let in light and air.

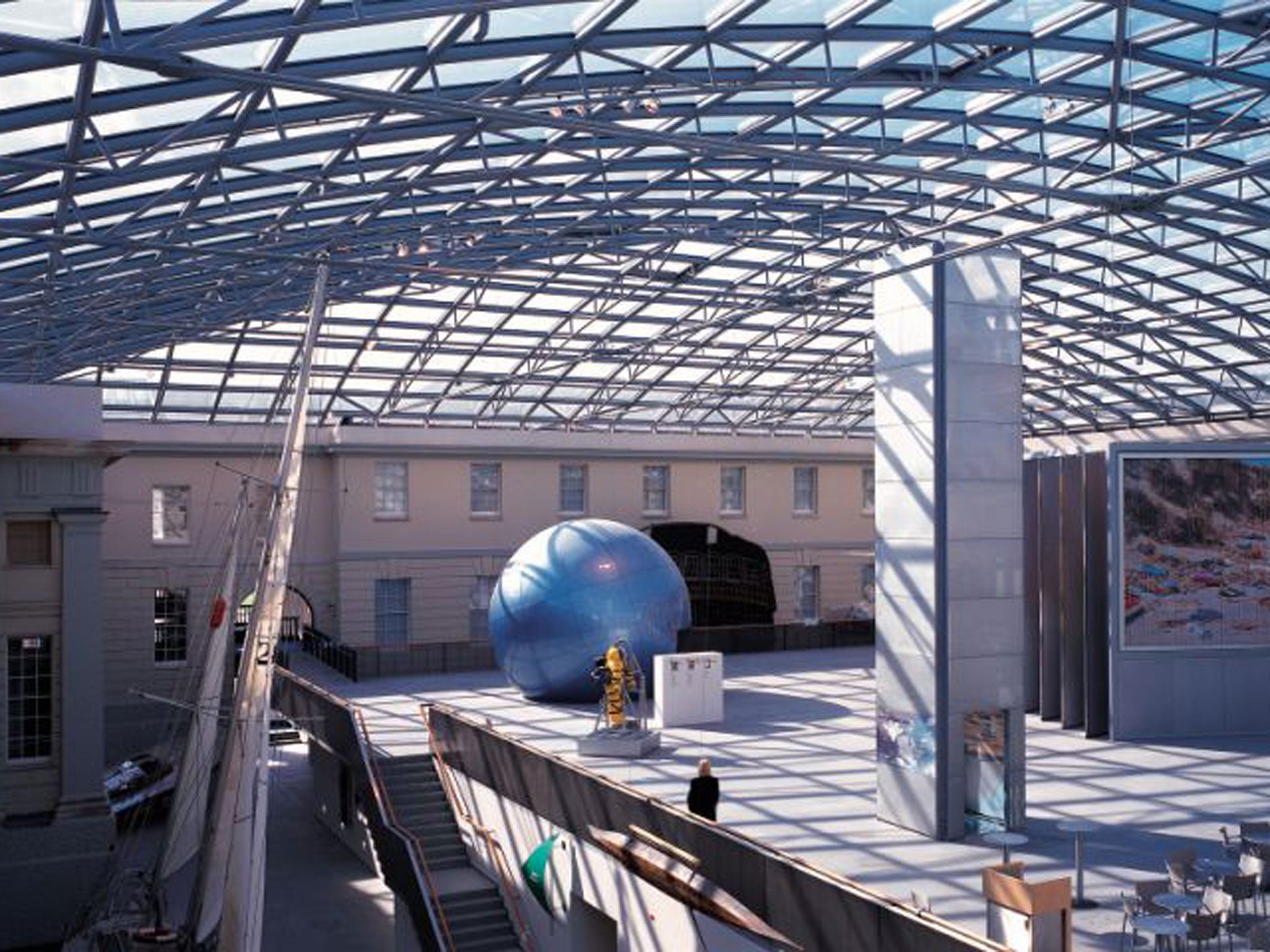

Sometimes, as at the Ashmolean in Oxford, you can only wonder at the ingenuity with which, making so few changes to the building's footprint, he seems to have flooded the building with daylight. Here, as at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, the Wallace Collection and the National Maritime Museum, Mather used structural glass to extend the original fabric and provide sometimes unexpected, but always wonderful, views.

He had acute intelligence, allied to the priceless ability to populate a space in his imagination, which made him the ideal architect for places through which people moved and congregated, such as university buildings, galleries and the river front of the South Bank; but also, perhaps surprisingly, for restaurants. He was the master of the convivial space, as he was of the listed structure.

Born in Portland, Oregon in 1937, Mather first studied architecture there, qualifying in 1961. Having built some timber houses in his heavily wooded home state, he came to London in 1963 to study urban design at the Architectural Association. Mather taught at the AA and in the late 1970s revamped the interior spaces of its Bedford Square terrace of Georgian townhouses.

He loved London and decided to stay, designing schools in Yorkshire for Lyons Israel & Ellis, and worked for Southwark Council, before opening his own practice, Rick Mather Associates, in Camden Town in 1973. He first came to my attention when he designed a series of restaurants for the Zen chain in London, Hong Kong and Montreal from 1985-1991; these often incorporated an interior water feature, as did the one in Hampstead, and the space was as exciting as the regional Chinese food.

In 1991 when he designed the Times headquarters in Wapping it had the best environmental rating of any London office building; his practice was far-seeing when it came to sustainability and low-energy design. He won about a dozen RIBA awards and competitions, along with a number of Civic Trust and other awards. Though he did not win the 2010 Stirling Prize for his Ashmolean extension (he was shortlisted, but the judges gave it to Zaha Hadid for her MAXXI Museum of 21st century arts in Rome), he was by far the popular choice in the polls.

Visitors to the 17th century Ashmolean enter via a six-storey atrium awash with natural light from a part-glazed roof, and see alternating single and double storey-spaces, with a wondrous curved staircase snaking down one wall. On the top floor floats a chic restaurant with a glass wall that opens onto a large terrace. Mather had a strong association with Oxford, having done projects in 1995, 2002 and 2008- for Keble College, The Queen's College (2006-) and Corpus Christi College (2009), and Mansfield College.

Mather's firm also did work for the University of East Anglia, London Metropolitan University, the Universities of Cambridge (where the new library for Christ's College will be finished next year), Reading, Southampton, Lincoln and Liverpool John Moores University; residential sites for Milton Keynes, Brent and Camden in London; the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith; and the private commission for Klein House, Hampstead. The extension of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond was completed in 2010, and in 2012 his firm won the commission to extend the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts and last year to design a £100m refurbishment of Centre Point in London.

In some respects, though, it was the commission to prepare a master plan to link up the buildings and spaces of the South Bank that made Mather a star in the international architectural firmament. Others had tried and failed, Terry Farrell in the late '80s and Richard Rogers in the mid-'90s had not been able to transform the hodge-podge of buildings and the brutalist concrete walkways that litter that stretch from Waterloo Bridge and the London Eye to the National Theatre. Mather noticed the spaces colonised by skateboarders and the fact that crowds were attracted by the buzz of events at the NT, the second-hand booksellers and the few eating places.

So he embraced all these and expanded them, encouraging cafés, restaurants and retail shops, creating a whole new public space between the Festival Hall and the river. This has spilled over, reanimating the spaces in front of the Festival Hall and even across Belvedere Road, so that the entire quarter is full of life and excitement.

On the councils of the RIBA, and the AA, and a trustee of the V&A Museum, Mather was a warm, easy conversationalist, who looked more laconic than he was. His presence brightened many a social gathering, and he had a broad and wide group of friends that included artists and writers of every sort. His partner was David Scrase, assistant director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Paul Levy

Richard Martin Mather, architect: born Portland, Oregon 30 May 1937; partner to David Scrase; died London 20 April 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks