Robert Rauschenberg: Restlessly experimental artist whose career was a celebration of change

"I was the 'charlatan' of the art world. Then, when I had enough work amassed, I became a 'satirist' – a tricky word – of the art world, then 'fine artist', but who could live with it? And now, 'We like your old things better'," said Robert Rauschenberg in 1972.

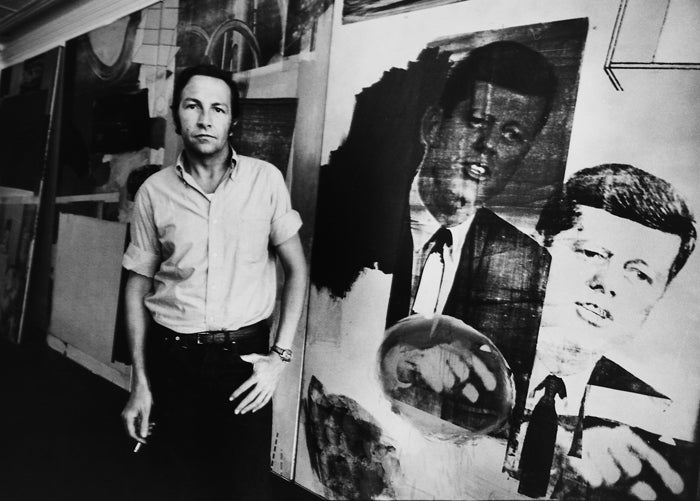

Rauschenberg, with his friend and erstwhile companion, Jasper Johns, was the most influential of the American artists who made their reputations in the 1950s, after the Abstract Expressionist painters who first established New York as the centre of the post-war art world.

Rauschenberg proved more varied and restlessly experimental than Johns, and became less easy to characterise and, accordingly, less lionised. He retained the belief that "art doesn't come out of art" despite "millions of institutions that would try to prove that's the case". His ceaseless questioning of art's relation to life is condensed in the statement: "Painting relates both to art and life. Neither can be made – I try to act in the gap between the two."

Building on European Dada and Surrealism, notably Marcel Duchamp and Kurt Schwitters, he formed a link between Abstract Expressionsim and Pop Art, Conceptual, Performance and Process Art. His career was a celebration of change as he helped break down divisions between painting and sculpture, painting and photography, photography and painting, drawing and printing, sculpture and photography, sculpture and dance (principally with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company), sculpture and technology, technology and performance art. The art historian Robert Rosenblum wrote: "Every artist after 1960 who challenged the restrictions of painting and sculpture and believed that all of life was open to art is indebted to Rauschenberg – forever."

He was born Milton Ernest Rauschenberg (Robert was the name he chose) in 1925, in Port Arthur, Texas. His grandfather was a doctor who had emigrated from Germany and married a Cherokee; his father a utility worker. The family were so poor that his mother even made a skirt from the suit in which her brother's corpse had been laid out.

Rauschenberg studied pharmacology at the University of Texas, Austin, before being drafted for the Second World War as a neuropsychiatry technician in the Navy Reserve. The war was to prove his liberation. He was first inspired to be an artist from visiting the Huntington Art Gallery when stationed in California and, after demob, the GI Bill paid for him to go to Europe, where he studied in Paris at the Académie Julian. There he met his future wife, the painter Susan Weil, and she persuaded him to study at the progressive Black Mountain College, North Carolina, where the veteran abstract painter Josef Albers, "a beautiful teacher and impossible person", proved a formidable influence. "I'm still learning what he taught me," Rauschenberg said in his own old age.

An Albers' dictate was that students should start with materials and not with "retrospective speculations". On graduating, Rauschenberg moved to New York, where he attracted attention with silhouetted negatives made with blueprint paper, one of them illustrated in Life magazine. In New York he met the avant-garde and Zen-oriented composer, John Cage, with whom he taught at Black Mountain and collaborated on a Futurist/Dada event or "happening", as the American form was later labelled.

The 1950s were a particularly fertile period and many of Rauschenberg's most famous (at the time notorious) work dates from this decade. Much of it derived from the egalitarian belief that everything had a place in art and that the artist was not a superior being. "I think you're a born artist. I couldn't have learned it," he said in old age, "and I hope I never do because knowing more only encourages limitations."

His attitude challenged not just the hallowed post-Renaissance tenet that through the quest for truth the artist creates order and communicates feeling. Monochrome paintings with embedded lumps of screwed newsprint made the point. Rauschenberg is seen as taking the mickey out of the Abstract Expressionists and high art, but the truth is more complicated. "What we had in common was touch. I was never interested in their pessimism or editorialising. You have to have time to feel sorry for yourself if you're going to be a good Abstract Expressionist, and I always considered that a waste."

The monochrome paintings not only challenged king-of-the-castle gestural feats of self-expressionism, but equated with Cage's musical use of silence, which never was truly silent, as an active component. "I always thought of the white paintings as being not passive but . . . hypersensitive, so that one could look at them and almost see how many people were in the room by the shadows cast, and what time of day it was."

That they were also cheap to produce only enforced the egalitarian point. Quart cans of paint cost a mere 10 cents, which suited his budget at the time. "I would just go and buy a whole mass of paint, and the only organisation, choice or discipline was that I had to use some or all of it and I wouldn't buy any more paint until I'd used that up."

His most notorious early work was Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953). With deep trepidation, Rauschenberg asked one of the alpha males of Abstract Expressionism, Willem de Kooning, if he could have one of his drawings to destroy in this way. De Kooning did not approve, but in the end gave the young artist the most difficult to rub out. He was right. It took Rauschenberg three weeks and 15 different rubbers to achieve his witty desecration and homage.

Rauschenberg's homosexual preference ended his marriage in 1952 and soon led to an artistically productive relationship over a decade long with his contemporary Jasper Johns. Initially, they sometimes collaborated on window displays for Tiffany and other uptown New York department stores, under the pseudonym Matson Jones; but were soon established as the twin stars of the most glamorous of the new galleries, Leo Castelli.

Rauschenberg rapidly evolved his embedded surfaces into what he called "combines", loading his canvases with objects so that they eventually became free-standing works, half paintings/half sculptures. Monogram (1959) includes a stuffed goat wedged inside a car tyre – he also made tyre print paintings by running paint-covered tyres across paper. He said he felt sorry for people who considered junk ugly, "because they're surrounded by things like that and it must make them miserable" – another example of his rejection of pessimism.

The combines found a pictorial off-shoot when he used a transfer drawing technique, dissolving printed images from newspapers and magazines with a solvent, then rubbing them on to paper with a pencil. The technique was later adapted to canvas. These drawings, paintings and prints (notably with Universal Limited Art Editions and Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles) of multifarious magazine and news imagery became his trademark.

In the 1960s Rauschenberg's career reached its zenith. He became the first modern American artist to win first prize at the Venice Biennale, in 1964; the same year he stormed England with a retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery under the directorship of Bryan Robertson. Honours, awards and major shows followed, culminating in a retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, 2005.

Rauschenberg always held true to John Cage's dictum that "fear in life is the fear of change", to which he added the rider: "It's the only thing you can count on." True to form, 1963 found him performing on roller skates, wearing a parachute and helmet he had designed to the accompaniment of a taped sound collage. Combining art and technology, in collaboration with Billy Kluver at Bell Telephonic Laboratories, became a new obsession.

Latterly he worked on ever more ambitious projects and collaborations, one accurately described as The ¼ mile or 2 Furlong Piece. This extremism, always a tendency, was encouraged by working with an army of assistants in a two-storey, 17,000ft studio on Captiva Island, off the Florida coast. He maintained this protean activity even after suffering the partial paralysis of a stroke in 2002. Huge schemes involved equally great risks; but as he said in old age: "Screwing things up is a virtue. Being right can stop all the momentum of a very interesting idea." But, as he had ruefully acknowledged 40 years before, people still "liked the old things better".

The wit, charm and generosity of spirit which Robert Rauschenberg was noted for as a man – he gave millions of dollars to charity – is the hallmark of an immense and varied body of work, whose embrace of the mundane does not exclude much refinement and even a melancholy poetry.

John McEwen

In 1986 I was writing a magazine article in which I mentioned Robert Rauschenberg's celebrated Monogram, writes Rhoda Koenig. In his survey of modern art, The Shock of the New, Robert Hughes had described this as "the satyr in the sphincter", but he had once told me that Rauschenberg, amused by this, had confided, "It's about me and Jasper Johns." I included this in the article, which my editor prudently submitted, before publication, to the company lawyer. The lawyer told me, "We do not take Mr Hughes's word for a remark of this nature. We seek confirmation from Mr Rauschenberg." I took a deep breath and picked up the phone.

The assistant at Rauschenberg's studio was polite but protective. Rauschenberg, it seemed, was creating art at that moment. What was the subject of my query?

"Er, it's about Monogram." I waited. The assistant came back and asked me to submit my question in writing. This was before computers, Rauschenberg had no fax, and we were going to press in a few hours.

"Could you tell him," I said, "that it is about the precise meaning of Monogram." The assistant left, returned, and made the same reply.

Another deep breath. "Could you tell him," I said, "that I need to confirm with him Robert Hughes's statement that Mr Rauschenberg told him Monogram is about him and Jasper Johns."

There was a pause, and the next thing I heard was a very loud voice. "This is Bob Rauschenberg. He said I said WHAT?" I made small, propitiatory noises.

"I'll have something to say to Bob Hughes the next time I see him!" the great artist bellowed. "Young lady, do you think that IF that were true, I would tell Bob Hughes? Do you think I would tell YOU?"

"Uh, no, sir, Mr Rauschenberg. Sir." There was another pause, and I heard a muted rumble, then chuckling.

"And besides," he said, "Jasper would kill me."

Milton Ernest Rauschenberg (Robert Rauschenberg), artist: born Port Arthur, Texas 22 October 1925; married 1950 Susan Weil (one son; marriage dissolved 1952); died Captiva, Florida 12 May 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks