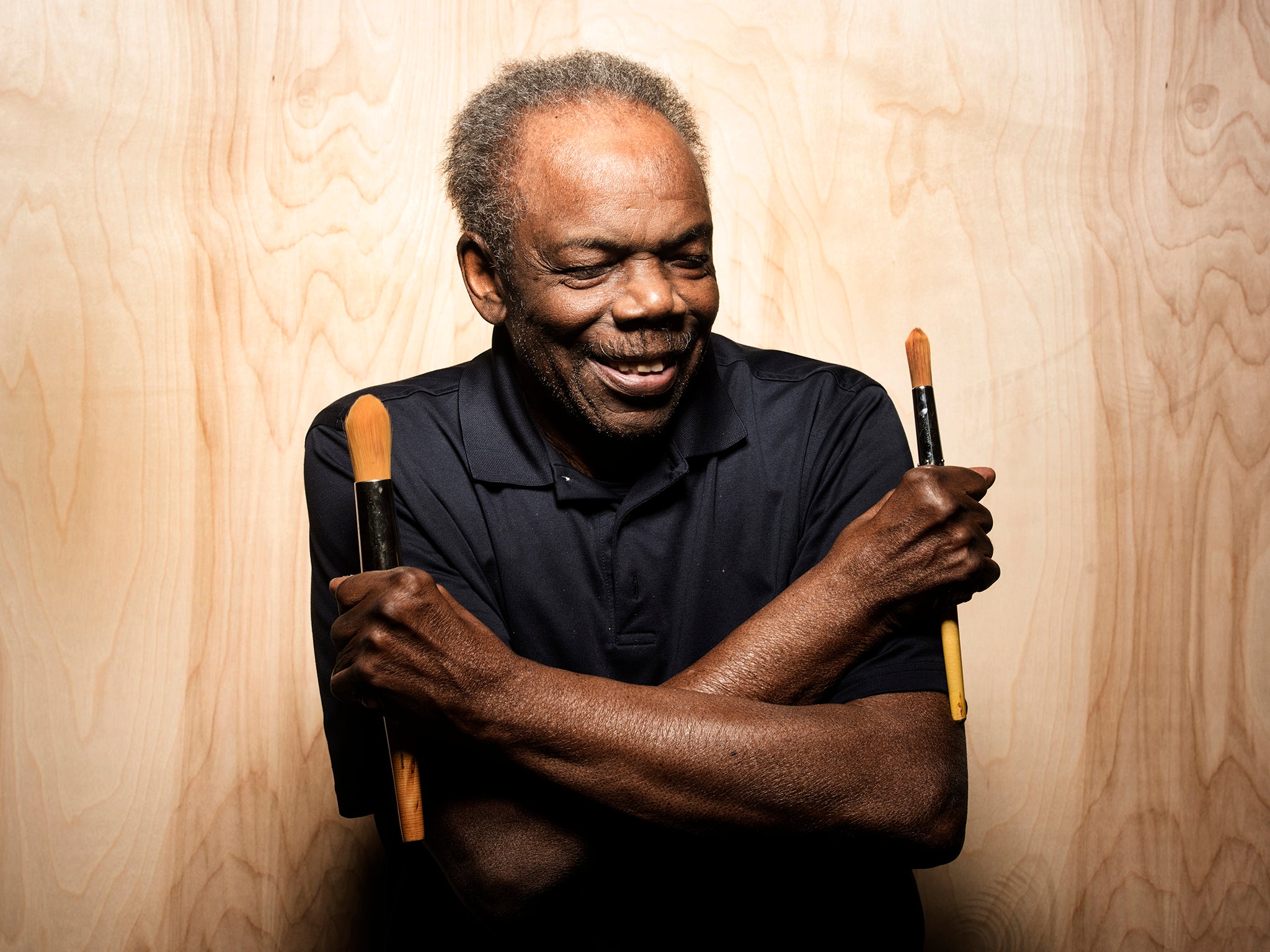

Sam Gilliam: Abstract painter whose art went beyond the frame

Known around the world for his flowing colour canvases, Gilliam pushed the boundaries of what could be considered art

Sam Gilliam, a Washington DC artist who helped redefine abstract painting by liberating canvas from its traditional framework and shaking it loose in lavish, paint-spattered folds cascading from ceilings, stairwells and other architectural elements, has died aged 88.

Resembling a giant painter’s dropcloth, his flowing, unstructured canvases, known as drapes, appeared in what was then known as the Corcoran Gallery of Art. The extravagantly coloured swags of fabric were suspended from the skylight of the Beaux-Arts building’s four-story atrium and prompted then-Washington Star art critic Benjamin Forgey to summarise the impact as “one of those watermarks by which the Washington art community measures its evolution”.

In a matter of months, Gilliam would become known throughout the country and later around the world as the painter who had knocked painting out of its frame. Over a career that spanned decades and several stylistic changes – not all of them as well received as his drapes – Gilliam would forever be known as an artistic innovator because of the Corcoran show.

Gilliam was never officially a member of the Washington Color School, the city-based painting movement whose practitioners rose to international prominence in the 1960s with a celebration of pure colour. But he quickly became acknowledged as the face of the Color School’s second wave.

He had many public commissions, including his career capstone, a commission by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which was a sprawling, five-panel work that was 28ft wide. He called it Yet Do I Marvel, after the poem by Harlem Renaissance writer Countee Cullen.

Gilliam continued to surpass himself – setting, and then breaking, multiple auction records for the price of his art, which in 2018 skyrocketed to $2.2m for his 1971 canvas Lady Day II. At 83, he was invited to show at the 2017 Venice Biennale – 45 years after he made history as the first African American artist to represent his country in that exhibition.

Virginia Mecklenburg, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum who organised the 2012 exhibition “African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era and Beyond”, said Gilliam’s claim to fame was the result of a strategic move. His immediate artistic forebears, including Jackson Pollock and the other nonrepresentational painters of the 1950s, had already thoroughly upended the notion of painting as a recognisable picture.

What was revolutionary about Gilliam, Mecklenburg said, was the way he took painting “one step beyond” what had already been accomplished. “He’s the one,” she said, “who gets painting off the wall.”

Gilliam’s legacy, she said, is therefore less stylistic than philosophical. By tearing canvases off the wall, and by draping them on and around other architectural elements, he gave an entire generation of artists implicit permission to do the same.

Gilliam was not the first artist to do so. By the late 1960s, a few other painters had begun to experiment with unstretched canvases, among them Richard Tuttle and William T Wiley. But it was Gilliam’s sculptural, even grandiose sensibility that took the once-flat painted surface into another realm, transforming it into something a viewer feels as much as sees.

Although most often identified with the drape paintings, a style he would return to throughout his career, Gilliam was also known for restless experimentation. In addition to the occasional foray into more-traditional stretched canvas, he also explored collage, hinged wood panels and other forms of three-dimensional construction.

Alex Mayer, a sculptor who worked for many years as Gilliam’s studio assistant, said: “Sam loved turning things upside down.” The one constant, Binstock wrote, was the “intimate experience of paint’s physical character”.

By his own account, Gilliam estimated that he went through more than 100 gallons of paint a year. Not all of that ended up on canvas. For many years, he lived in a Mount Pleasant rowhouse whose exterior was an ever-changing advertisement for its owner’s line of work. The bright blue porch might be complemented by a purple fence, a red front door and yellow window trim. The paint-spattered floors were artworks in themselves.

Gilliam’s critics were not always sympathetic to his experiments. Reviewing a 1981 New York show of collaged paintings, which featured pieces of canvas patched together like a quilt, critic Kay Larson accused the artist of “worrying the canvas surface … like a neurotic architect who can’t keep his hands off his work”. At the same time, others chided him for being too safe.

Although he rose to prominence at the height of the civil rights movement, Gilliam’s paintings for the most part avoided Afrocentric, or even overtly political, themes. (The 1969 canvas, April 4, honouring the death of Martin Luther King Jr, was a rare exception.) It was a stance he was sometimes taken to task for, Gilliam told The Washington Post in 1993.

“I remember when [Black activist] Stokely Carmichael called a group of us together to tell us of our mission,” Gilliam said. “He said, ‘You’re Black artists! I need you! But you won’t be able to make your pretty pictures any more.’”

Sam Gilliam Jr was born on 30 November 1933, the seventh of eight children. His father was a carpenter and his mother was a seamstress.

“I learned to draw quite early,” Gilliam once told arts writer Joan Jeffri. “I made lots of things out of clay, and then I started to paint quite early, about 10 years old, just bought some paint and started.” He added that his facility with art was spurred by the fact that his father “left a lot of materials around – hammers, saws, wood”.

In 1955, Gilliam graduated from the University of Louisville with a bachelor’s degree in creative art. After a brief stint as an army clerk in Japan, he returned to his alma mater and received a master’s in painting in 1961.

In 1962, Gilliam arrived in Washington DC, following his college sweetheart and new bride, the former Dorothy Butler, who had just been hired as a Post reporter and would later become a columnist for the paper. The marriage ended in divorce.

Survivors include his wife, Washington art dealer Annie Gawlak; three daughters from his first marriage; three sisters; and three grandchildren.

Gilliam accepted a position as an art instructor at Washington DC’s McKinley Technical High School, where he would continue to work for five years, in the first of several teaching positions.

In Washington, the artist found conditions that were ripe for artistic reinvention. Foremost, the city’s culture was more racially open than the one he had come from. Dupont Circle was the centre of a burgeoning art scene, centred on the Washington Color School.

Gilliam’s early, close friendship with Thomas Downing, a Color School painter who acted as a mentor, would prove instrumental in his transformation from representational painter to abstractionist.

Under Downing’s tutelage, Gilliam began to let go of everything he had been taught about traditional painting, working more loosely, rapidly and spontaneously, allowing colours to bleed into one another, and letting the paint do what it will.

If there was a single, epiphanic moment when Gilliam was moved to remove his paintings from their wooden supports and to hang them like drapes, the artist was often cagey about when – or even whether – that occurred.

Also a natural teacher, Gilliam was generous with his time, opening his studio door to any artist or student who sought his counsel. Yet he was also equally well known for a prickly and at times volatile temper.

In 1981, while participating in a panel discussion about institutional support of local arts organised by the Corcoran, Gilliam, who was one of the panellists, loudly denounced Corcoran director Peter Marzio – another panellist – as a “turkey” for promoting national artists over homegrown ones.

Although Gilliam may have been giving voice to the frustration that many in the room already felt, the indelicacy of his comment – not to mention the irony of it, seeing as the speaker’s first big break came from the Corcoran – came across as unseemly. Gilliam’s comment was met with derision from the audience

Two years later, at the opening of another Corcoran exhibition of Gilliam’s work, the artist was handed an axe and a block of wood, symbolically burying the hatchet in the presence of museum administrators.

If he was, at times, a combative presence in the very community of which he was recognised as the dean, his adoptive city was so quick to forgive because it was so proud of him. “He could be a diva,” Sondra Arkin, a friend and fellow painter, said, “but he was our diva.”

Sam Gilliam, abstract artist, born 30 November 1933, died 25 June 2022

© The Washington Post

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks